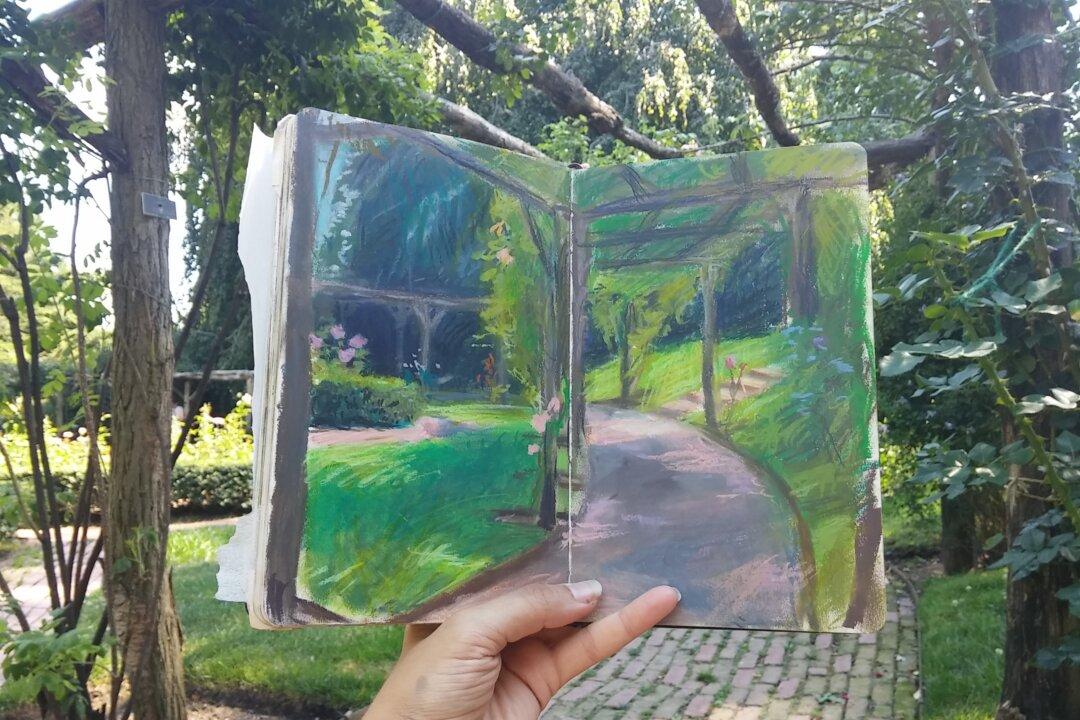

NEW YORK—Jessica Artman set aside her “stepping stones” to be shipped to Paris. She called those drawings and paintings “the lessons”—not her best work, nothing for sale, but she would never get rid of them either, she said, because they were “all ‘aha! moments.’” Those breakthroughs on paper will serve as good examples when she begins teaching at the recently founded Paris Academy of Art this October.

She pointed at a pile of her artwork, supplies, and books waiting to be packed in her studio space at Grand Central Atelier, where she has been teaching and developing her work as an artist in residence. “I’m consumed with the idea of packing. Once that’s done, then I think I can really start to get excited,” she said, full of anticipation.

[gallery size=“medium” ids=“2284554,2284555,2284559,2284556”]

Art ateliers and academies have reemerged in the past 20 years, mostly in the United States and Europe. But the Paris Academy of Art is the first to be established in Paris since the classical training offered at L'École des Beaux-Arts had, by 1968, been practically obliterated. The new academy is very small in comparison to the massively influential institution that reached its peak in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but it is starting to fill a major gap in art education in the city that is home to the Louvre—the world’s largest art museum, no less.

In the 19th century, Paris was the place to be for artists who wanted to show their work at the prestigious Paris Salon. American students flocked there to learn from artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme. Some of these Americans, like George Bridgman and William McGregor Paxton, passed on the academic art training back in the United States, enabling the tradition to be kept alive, just barely, through the 20th and 21st centuries.

Fast forward to 2017, and Artman, together with her boyfriend, sculptor Charlie Mostow, and fellow painter Patrick Byrnes, will be part of a new, small batch of Americans in Paris contributing to the Western art heritage, which is rooted in the fundamentals of drawing, painting, and sculpting from life.

[gallery size=“medium” ids=“2285691,2284565,2284563”]

In her studio, Artman pointed out some of the academic figure drawings in her portfolio. Some were shaded smoothly, with barely detectable pencil marks. Those took her about 80 hours to complete. In some of her other drawings, small hatch marks were visible. Those took her about half the time, she explained. Yet in those abbreviated, hatch-marked drawings, she had enough information and anatomical knowledge to be able to continue modeling the form into a smooth finish, without having to look at the model again. For the curriculum at the Paris Academy, she foresees working with the model less than 80 hours.

Every atelier or academy has its unique approach, based on the training and background of the teachers. Artman looks forward to contributing to the traits of the new academy.

Defending Painting

From a young age, Artman always knew she wanted to paint. She studied at Florida Southern College, where she completed her bachelor’s degree in fine art. The curriculum was typical of fine art programs, which encourage multidisciplinary skills rather than the specific techniques taught in ateliers. Later, she studied at the National University of Ireland in Galway, where she had to stand her ground.

“It was very contemporary. The whole time, I was basically defending painting,” she said. “Every project or concept that I had thought of for a painting, I was told, ‘You should do this as an installation,’ or ‘You should do that as a performance piece,’ or ‘Make a video.’ It was very challenging. ... While I did learn a lot, I never felt I was given what I wanted. I felt that they were trying to mold me into something else,” she said.