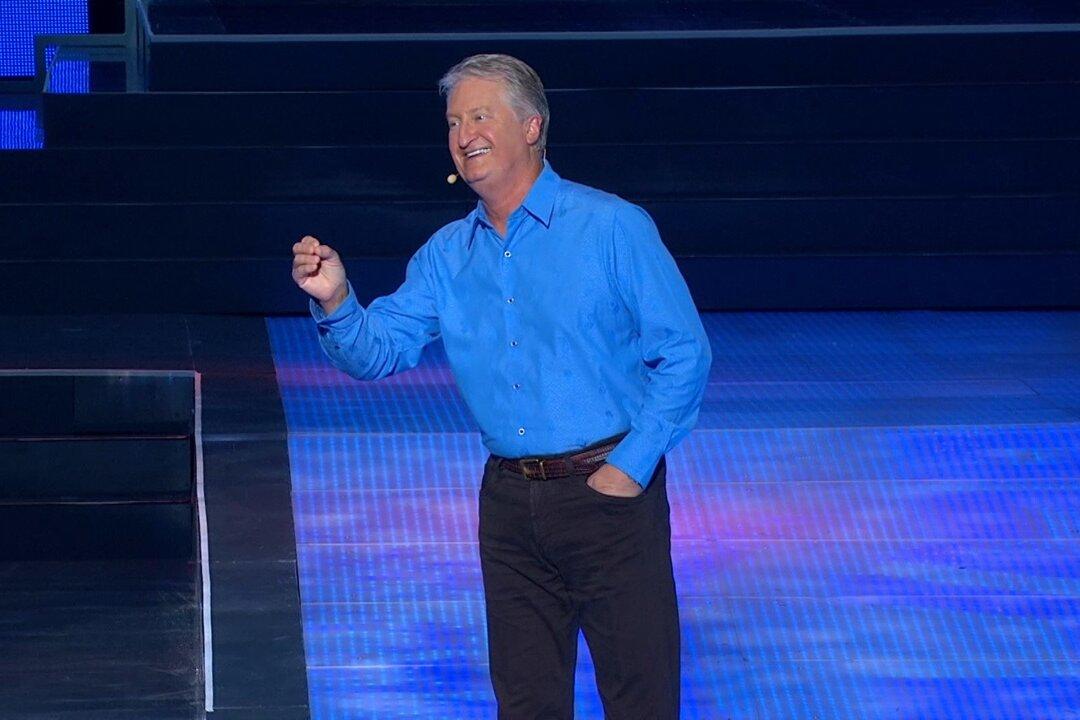

Before Andy Andrews was helping corporations double their profits, helping special operations military personnel refine their techniques, helping sports teams win and achieve, before he became “The Professional Noticer“ with listeners in 114 countries and the bestselling author of several books, he was homeless and hiding under a pier in Orange Beach, Alabama.

At age 19, Andrews lost his mother to cancer and his father to a car accident, all within a year. Between grief and bad financial decisions, he soon found himself with nothing and no one. And then he met Jones—a mysterious, white-haired man who would pop up out of nowhere before disappearing without a trace, who noticed truths no one else saw.