Alexander Borodin (1833-1887) was one of the great melodists of Russian music but composing was a sideline for him. He was a renowned chemist and, while he worked on his opera “Prince Igor” over an 18-year period, it was unfinished at his death. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazounov orchestrated it and made their own deletions and additions.

The new production of “Prince Igor” at the Met is the first at the house since 1917, when it was performed in Italian. Now, it is back in a revised version, with direction and sets by the visionary Dmitri Tcherniakov (making his Met debut). There is quite a bit of musical tinkering; the overture is gone (despite the fact that Glazounov based his orchestration based on his memories of the composer playing it on the piano) and there is a new ending, imported from another Borodin work. The time period has been updated from the 12th century to, according to the Playbill, “a timeless space inspired by different periods of Russian history and architecture.”

At the beginning of the opera, Prince Igor (the ruler of the city-state of Putivl) is about to lead a military campaign against the invading Polovtsians, a nomadic Asian tribe. His wife Yaroslavna begs him to stay but he goes off anyway, leaving her in the care of her brother, Prince Galitsky. The war is a disaster; the faces of dead and wounded soldiers (including Igor) are projected on a screen.

Igor has a dream that he is in a field of red poppies with his son, Vladimir. The leader of the Polovtsians, Khan Konchak, appears and treats Igor as an honored guest rather than a mere captive. Konchak’s daughter Konchakovna is in love with Vladimir. Meanwhile, back in Putivl, Galitsky and his men go on a drunken rampage. Yaroslavna is unable to control him and Galitsky schemes to take over permanently. However, when the Polovtsians attack, he is killed.

With Putivl in ruins, Igor returns, haunted by visions. He blames himself for his army’s defeat and urges his people to rebuild their city.

Contrary to the often cited view that the opera is a tribute to Russian nationalism, the invaders are not depicted as villains. Konchak is a civilized and humane fellow and his daughter really loves Vladimir. The nasty characters are Galitsky and his followers, who kidnap and rape young women. Igor is a complex character, heroic but afflicted by nightmare visions and self-doubt.

The cast is mostly Russian, with the outstanding bass Ildar Abdrazakov in the title role. As in Verdi’s “Attila” in which he also had the lead, the towering singer looks like a warrior. In fact, he claims to be a direct descendant of Genghis Khan. He is charismatic, acts with conviction and sings smoothly, with a full sound (albeit more lyrical than those who usually sing this role). Oksana Dyka sang beautifully with an authentic Russian sound as Prince Igor’s wife, Anita Rachvelishvili was excellent as Konchak’s daughter, Stefan Kocan was amusing as Khan Konchak and tenor Sergey Semishkur sang with passion and ringing high notes. As the villain Galitsky, Mikhail Petrenko acted with gusto. His singing, however, was a disappointment, especially in his big aria, one of the most popular in Russian opera.

“The Polovtsian Dances” (with the melody that later appeared in the Broadway musical “Kismet” as “Stranger in Paradise”) is a knockout. Someone had the brilliant idea of placing the chorus in the front box seats on both sides of the hall while dancers performed on stage.

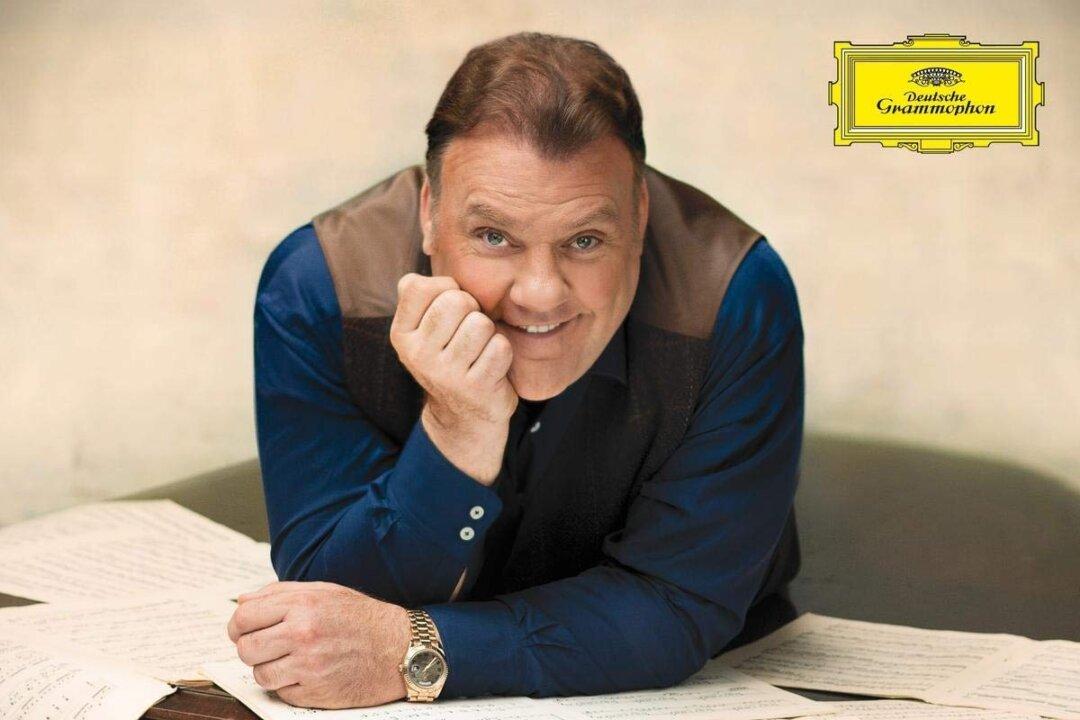

Conductor Gianandrea Noseda led an exciting performance. Though it runs over four hours, the production continuously held my interest, even if there are still flaws in this version of Borodin’s unfinished opera.

“Prince Igor” plays at the Metropolitan Opera intermittently until March 8. The live telecast is on Saturday, March 1.