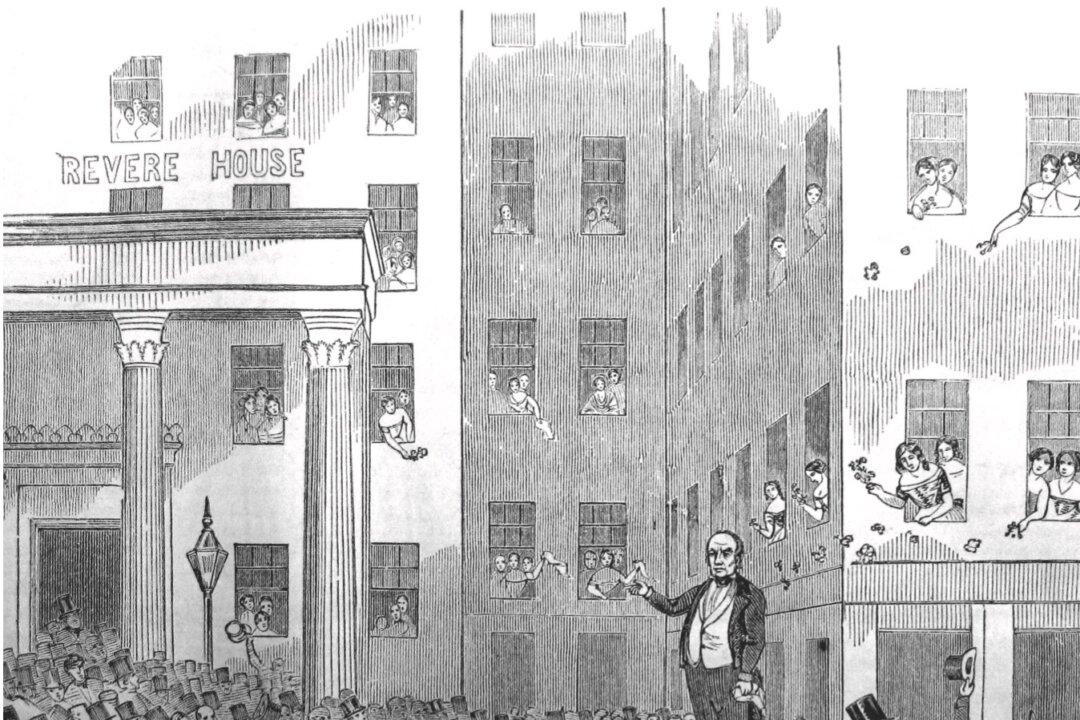

A contemporary, journalist Oliver Dyer, described Daniel Webster this way: “The head, the face, the whole presence of Webster, was kingly, majestic, god-like.”

That third description stuck. Others began referencing the senator and orator from New Hampshire as “Godlike Daniel.” His words could move the hearts of his listeners, and his vibrant voice often brought many in his audience to rhapsody and sometimes tears, but it was his appearance—his dark complexion, his luxuriant, wild hair, his eyes “like glowing coals”—that earned him his nickname.