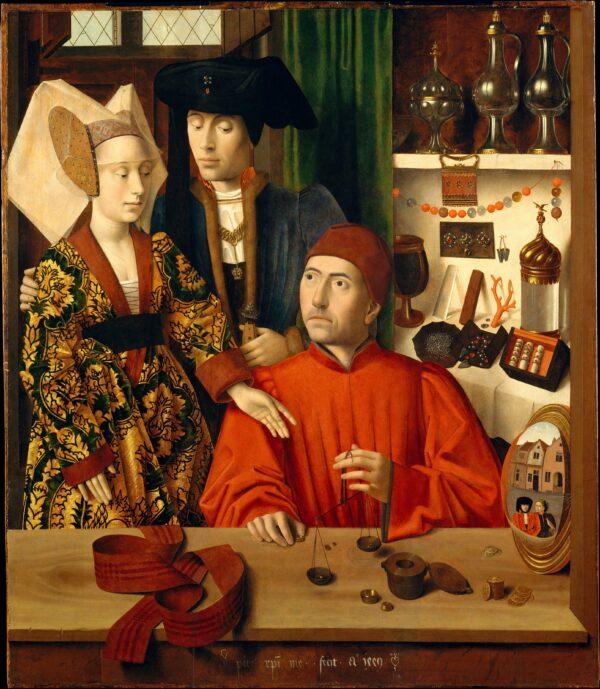

In the painting “A Goldsmith in His Shop,” a finely dressed couple are eagerly purchasing a wedding ring. The man tenderly wraps his arm around his fiancée, while she happily gestures to the goldsmith who is weighing a ring on a set of scales. The goldsmith, dressed in a rich-red robe, concentrates on his customer’s request as he prepares the ring for sale.

"A Goldsmith in His Shop," 1449, by Petrus Christus. Oil on oak panel; 39 3/8 inches by 33 3/4 inches. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975; Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public Domain