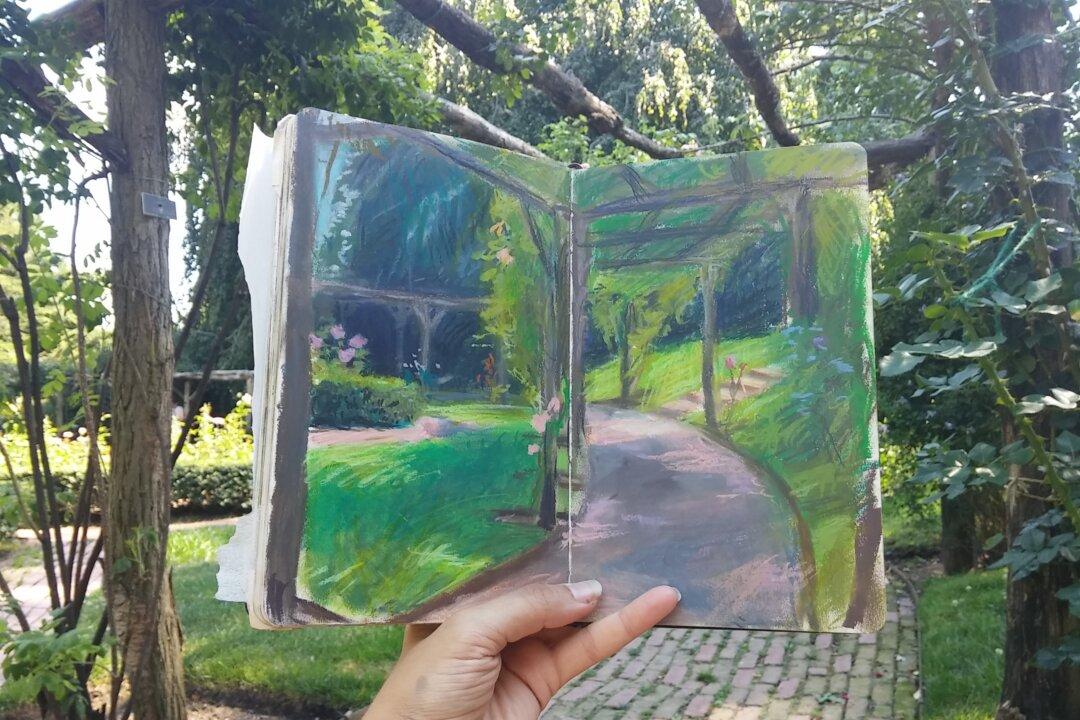

NEW YORK—A “music in context” concert, put on by Aspect Foundation for Music and Arts, feels like how you might imagine those 19th-century salons associated with literary and artistic milieus to be: both amusing and intellectually stimulating. Having conversations over drinks or listening to discourses and chamber music in a relaxed, informal atmosphere—this synthesis of music, history, and social culture—is perfectly geared to pique your curiosity.

Each Aspect concert centers on a specific theme, such as musical capitals like Vienna or Weimar, dialogues between composers, great muses, hidden gems of rarely played pieces, or compositions inspired by paintings or literary works. Before the concert begins, a world-renowned speaker gives an illustrated presentation explaining different aspects and anecdotes about the theme and the music the audience is about to hear. At the end of the concert, people keep mingling, having long conversations that evolve beyond small talk. You get a sense that despite salons having dwindled in the 1940s, the spirit of that custom continues to live on in Aspect’s concerts.