The Italian peninsula has long been a land where the fine arts have flourished under a meticulous eye and in an idyllic setting. Wealthy and demanding benefactors connected their prestige and power to art.

Nowhere else has fine art played such an iconic role: it set a precedent to guide humanity toward lofty ideals beyond the purely material, and shaped our view of the world through its images.

Listed here are a few of the most significant artists that pushed the realm of fine art to new heights either in technique or expression.

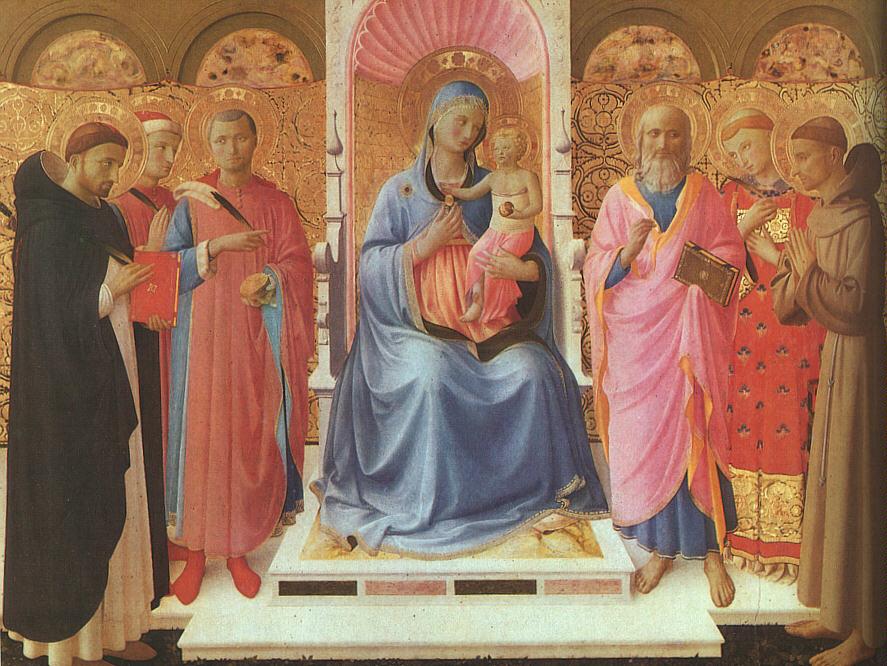

Fra Angelico (1395–1455)

As his name suggests, Fra Angelico means “angelic friar.” Fra Angelico was said to have stirred the transition from late Gothic paintings, which resembled iconography, to the classic Grecian style. When not working for wealthy patrons, he revealed his devout, humble nature through frescoes painted in the San Marcos friary.

The images he portrayed varied from his counterparts in that he depicted Mary and the saints as people rather than lofty, inaccessible beings. His constrained palette and gentle, relaxed figures give his paintings a surreal quality.

“Annalena Altarpiece.” Tempera on wood, 1437-1440, 70.87 inches by 79.53 inches. Museo di San Marco (Florence, Italy).

Leonardo Da Vinci (1452–1519)

A student of Andrea del Verrocchio, Leonardo Da Vinci shocked the art world with a little blue angel.

In Verrocchio’s painting “The baptism of Christ,” the young Leonardo was assigned to paint a little angel in the far left corner. Leonardo’s charming little blue angel shows his grace with the brush, his ingenuity, and calm sensibility and was the beginning of his career with the Medicis and his renown as an artist.

His style and ability to capture motion and expression set him apart from all others of his time.

Leonardo developed the techniques of layering and under-painting, applying thin layers of paint on top of others, creating a dynamic and realistic effect. He also developed a technique called sfumato, applying a dark glaze around his figures which gave them a hazy and blurred periphery.

He constantly pushed his limits and developed techniques which inspired his contemporaries and thereby brought about a golden age in Italian art.

“The Baptism of Christ [detail].”Oil on wood, 1475, 69.69 by 59.45 inches. Galleria degli Uffizi (Florence, Italy).

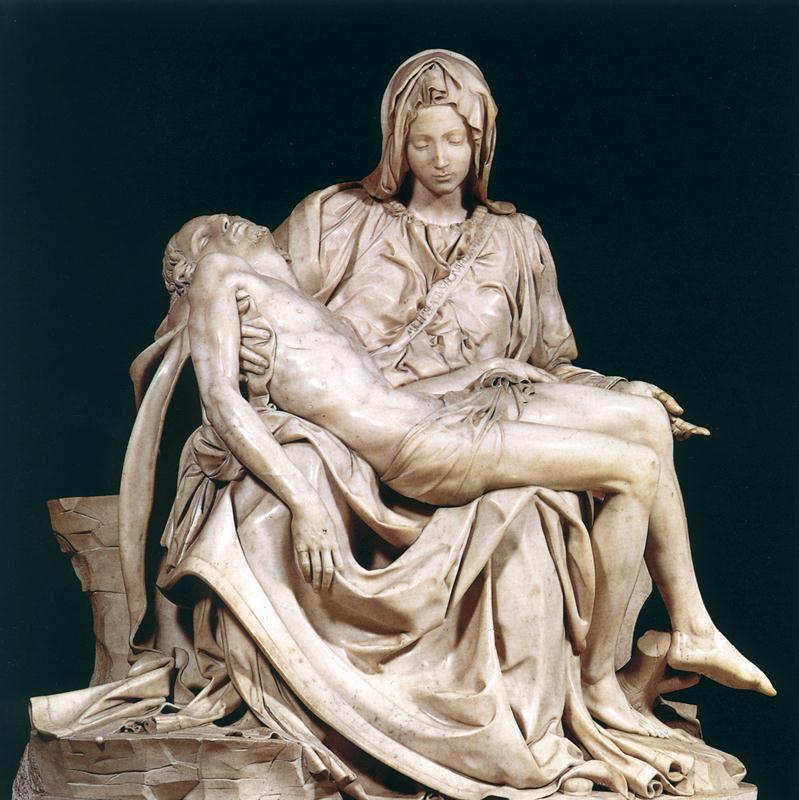

Michelangelo (1475–1564)

It was in sculpture that Michelangelo set himself apart. Unearthing classical statues of Greek and Roman antiquity, it was not historians the experts turned to, but Michelangelo to understand them.

Michelangelo learned cast drawing at a young age in the statue gardens, as well as foreshortening, and the principles of light and form.

He said he always felt at home around the stoic, marble figures. Pouring his heart into one of his first real commissions, he was to carve perhaps the most beautiful statue ever, the “Pieta.”

“Pietà.” Marble, 1499, 68.5 by 76.77 inches. Basilica di San Pietro (Vatican, Holy See (Vatican City State).

Raphael (1483–1520)

Breaking from traditional Christian fare into the world of classicism, Raphael succeeded in pushing the boundaries possible for art in the high renaissance. The princely painter was never far from royalty.

He succeeded in the footsteps of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, both of whom can be found in his frescoe “The School of Athens.”

Raphael’s flair was charm, and it exuded from his mind into matter. He considered the location of his characters a most important aspect of his works. He conceived and created livable, three-dimensional spaces to bring the viewer further into the scene.

“The School of Athens.” Fresco, 1509. Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici (Vatican, Holy See (Vatican City State).

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) (1485–1576)

By the mid-16th century, much of the artwork being produced held to tried and true methods of composition and color. The standard triangular composition of “Madonna with Child” became somewhat of an artistic faux-pas.

Titian invited the viewer into his paintings and united all of the ideals of conventional composition. An interesting angle on “Last Supper” and “Pesaros Madonna” give a sense of motion and liveliness to the painting, a sense heretofore unrealized.

“Pesaros Madonna.” Oil on canvas, 1519-1526. Private collection.

Guido Reni (1575–1642)

Guido Reni conceived the familiar expression of a figure looking upward to heaven, which was copied by many other artists, and was said to have been influenced by Raphael. He embodied the theatrical style of the baroque artists with their vivid, earthy tones and use of dramatic lighting.

The unconventional artist took a keen disinterest in women, though he was well known for his paintings of the virgin Mary. One of his most recognized works is “The Archangel Michael Defeating Satan.”

“The Archangel Michael Defeating Satan.” Oil on canvas, 1635. Private collection.

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

The palace painter Giovanni Barttista Tiepolo earned a reputation as one of the most grandiose artists of the 18th century. Adapting the epic scale of Paolo Veronese to his own unique style, Tiepolo set the art world back—literally, as viewers leaned back to see his lofty paintings high in the churches and palaces in Italy.

In Würzburg, Germany, high in the New Residenz palace, once the residence of Prince Bishop Karl Philip von Greiffenklau, one can view one of the largest frescoes in the world, his “Allegory of the Planets and Continents.”

“Christ Carrying the Cross.” Fresco, 1737-1738, 177.17 by 203.54 inches. Sant'Alvise (Venice, Italy).

Antonio Canova (1757–1822)

Antonio Canova reached the pinnacle of neoclassical ideals by emulating the polished and perfect style of ancient Greece and became one of the most celebrated sculptors of the early Enlightenment era. Canova had an alchemic ability to shape marble into flesh, and the human spirit into motion, a central feature in his works.

Among his most notable sculptures were “Cupid and Psyche,” and a bronze statue of Napoleon in the likeness of Mars titled “Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker.”

“Dancer.” Marble. Hermitage (St. Petersburg, Russian Federation).