In the world of public health, important information can be hard to obtain. For example, we know children drive many infectious disease epidemics and that infection levels often decline during school holidays. However, finding out how many children actually change their behaviors over time, and what effect it could have on outbreaks, is much more difficult. But what if the children themselves could help gather the data?

To find out more about populations—and the diseases that affect them—public health researchers are increasingly turning to new sources of data. Some groups have used mobile phone data to map the spread of malaria. Others have analyzed Twitter posts to understand attitudes toward vaccination.

Sometimes the public takes on an even more prominent role, becoming an active part of a research project. These “citizen scientists” are helping researchers to get at hard-to-access information and find out what it could mean for our health.

Schools and Social Contacts

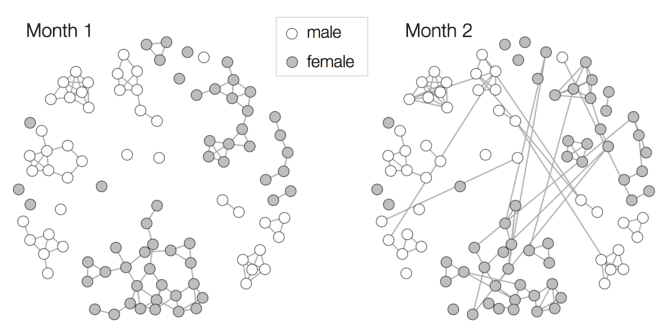

From measles to influenza, school children—who interact with more people than adults—play an important role in disease transmission. The challenge is to find out how children interact and travel, and how much these patterns vary.

Over the past few years we’ve worked with schools to survey pupils’ travel and social contact patterns. Rather than rely on us academics to run everything, we’ve instead encouraged pupils to help design the surveys, collect the data, and analyze the results.

There are several advantages of having pupils on the research team. When designing a survey, they can advise on what questions will be relevant and point to any potential pitfalls in collecting responses. With their inside knowledge, they can also help explain any outlying results.

Including pupils in the research also makes it possible to conduct projects on a bigger scale. Instead of being limited to one-off surveys in a few classes—as a team of academics might be—groups of pupils can carry out larger studies over a longer period.