A new museum dedicated to the advanced technological inventions of ancient Greek scientist Archimedes, has just opened up in Ancient Olympia, Greece, according to a news announcement in the Greek Reporter. More than fifty incredible inventions of ancient Greece have been reconstructed, including Archimedes’ screw, the robot-servant of Philon, the automatic theatre of Heron, ancient war machines, and the famous analogue ‘computer’ of Antikythera, covering the period from 2,000 BC up to the end of the ancient Greek world. The exhibition highlights the brilliance of the inventors of our past, and the amazing creations that laid the foundations for the technology we see today.

The museum was an initiative of engineer Kostas Kotsanas who has also established the Museum of Ancient Greek Technology in Katakolo, southern Greece. According to Kotsanas, the museum aims to highlight even the most unknown aspects of Archimedes’ scientific work, which shows that the technology of the ancient Greeks was not that far from the beginnings of modern technology.

Here are just five of the impressive inventions featured in the new exhibition:

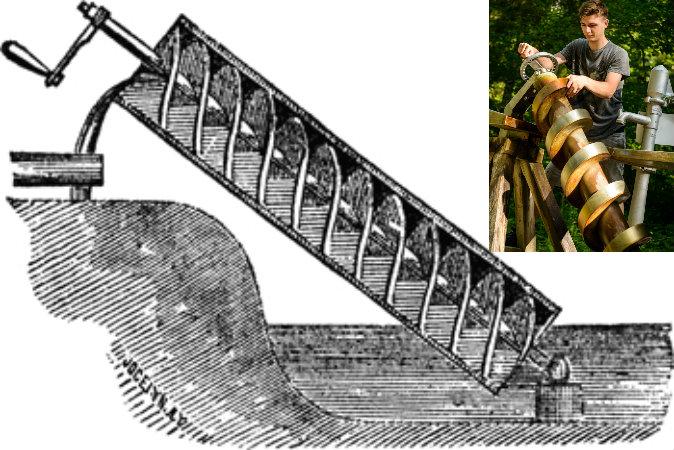

Archimedes’ Screw

Archimedes of Syracuse (c. 287 BC–212 BC) was an Ancient Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, inventor, and astronomer. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists in classical antiquity. A large part of Archimedes’ work in engineering arose from fulfilling the needs of his home city of Syracuse. King Hiero II commissioned Archimedes to design a huge ship, the Syracusia, which could carry 600 people and would be used for luxury travel, carrying supplies, and as a naval warship. Since a ship of this size would leak a considerable amount of water through the hull, the Archimedes’ screw was purportedly developed in order to remove the bilge water. Archimedes’ machine was a device with a revolving screw-shaped blade inside a cylinder. It was turned by hand, and could also be used to transfer water from a low-lying body of water into irrigation canals. The Archimedes’ screw is still in use today for pumping liquids and granulated solids such as coal and grain.

Main image: Archimedes’ screw. (lanmacm via wikimedia commons); Top right: Young man pumping water with spiral pump/Archimedean pump. (Shutterstock)

The Robot Servant of Philon

Philo of Byzantium, also known as Philo Mechanicus, was a Greek engineer and writer on mechanics, who lived during the latter half of the 3rd century BC. Among his many inventions was a human-like robot in the form of a maid, who held a jug of wine in her right hand. When the visitor placed a cup in the palm of her left hand, she automatically poured wine initially and then she poured water into the cup mixing it when desired. The robot was created through a complex construction consisting of containers, tubes, air pipes, and winding springs, which interacted through variants in weight, air pressure, and vacuum. The result is the oldest known robot created by man.

Heron’s Automatic Theatre

Heron of Alexandria (c. 10 – 70 AD) was a Greek mathematician and engineer who is considered to be one of the greatest experimenters of antiquity. One of his more artistic creations was an automatic theatre that presented Nauplius, a tragic tale set in the period after the Trojan War. As (presumably) amazed playgoers watched, the doors to a miniature theater swung open, and animated figures acted out a series of dramatic events, including the repair of Ajax’s ship by nymphs wielding hammers, the Greek fleet sailing the seas accompanied by leaping dolphins, and the final destruction of Ajax by a lightning bolt hurled at him by the goddess Athena. The entirely mechanical play, which was almost ten minutes in length, was powered by a binary-like system of ropes, knots, and machines operated by a rotating cylindrical cogwheel. Even the sound of thunder was produced, created by the mechanically-timed dropping of metal balls onto a hidden drum.

Heron’s Automatic Theatre. (Screenshot/atelbauers/YouTube)

Archimedes’ Claw

The Claw of Archimedes (also known as the “iron hand”) was an ancient weapon devised by Archimedes to defend the seaward portion of Syracuse’s city wall against amphibious assault. Although its exact nature is unclear, the accounts of ancient historians seem to describe it as a sort of crane equipped with a grappling hook that was able to lift attacking ships partly out of the water, then either cause the ship to capsize or suddenly drop it. These machines featured prominently during the Second Punic War in 214 BC, when the Roman Republic attacked Syracuse with a fleet of 60 Quinqueremes under Marcus Claudius Marcellus. When the Roman fleet approached the city walls under cover of darkness, the machines were deployed, sinking many ships and throwing the attack into confusion. Historians such as Polybius and Livy attributed heavy Roman losses to these machines, together with catapults also devised by Archimedes.

Wall painting of the Claw of Archimedes sinking a ship, taking the name “iron hand” in the ancient sources literally. (Magnus Manske via wikimedia commons)

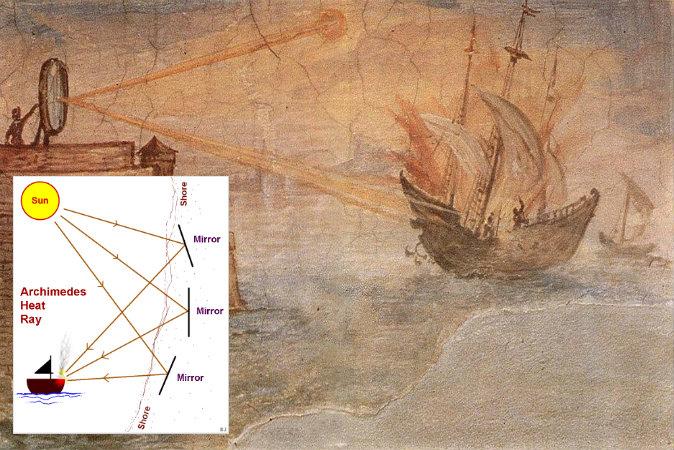

Archimedes’ Burning Mirrors

The 2nd century AD author Lucian wrote that during the Siege of Syracuse (c. 214–212 BC), Archimedes destroyed enemy ships with fire. Centuries later, Anthemius of Tralles mentions burning-glasses as Archimedes’ weapon. The device, sometimes called the “Archimedes heat ray”, was used to focus sunlight onto approaching ships, causing them to catch fire. It has been suggested that a large array of highly polished bronze or copper shields acting as mirrors could have been employed to focus sunlight onto a ship. This would have used the principle of the parabolic reflector in a manner similar to a solar furnace. A test of the Archimedes heat ray was carried out in 1973 by the Greek scientist Ioannis Sakkas. The experiment took place at the Skaramagas naval base outside Athens. On this occasion 70 mirrors were used, each with a copper coating and a size of around five by three feet (1.5 by 1 m). The mirrors were pointed at a plywood mock-up of a Roman warship at a distance of around 160 feet (50 m). When the mirrors were focused accurately, the ship burst into flames within a few seconds.

Main picture: Wall painting Archimedes’ mirror being used to burn Roman military ship. (Magnus Manske via wikimedia commons). Bottom left: A conceptual diagram of an Archimedes heat ray. (Tablizer via wikimedia commons)

The newly launched museum includes 24 replicas of Archimedes’ inventions such as Archimedes’ screw, Archimedes’ mechanical planetarium, the diopter, the odometer, the hydrostatic paradox, the burning mirrors and war machines, as well as the inventions of other ancient Greek scientists. City mayor Thymios Kotzias said that the museum will contribute to bringing more tourists to Ancient Olympia.

Republished with permission from Ancient Origins. Read the original.

*Vintage art showing drawings by Leonardo Da Vinci via shutterstock