Impact of Radiation on Ocean Water May Be Seen in Long Term

The radioactive consequence for marine life and ocean water could be harmful in the long run after the Japanese nuclear plant disaster.

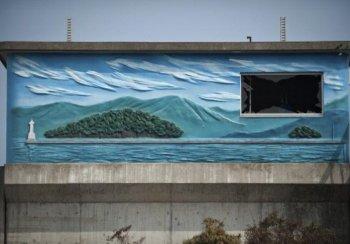

A mural depicting the sea is seen in the tsunami-damaged city of Yamada, in Iwate prefecture on March 25, 2011. Nicolas Asfouri/AFP/Getty Images

|Updated: