The China Manned Space Engineering Office (CMSEO) claimed the 19,000 lb Tiangong-2 (Heavenly Palace 2) had exceeded its original mission life, and ground control adjusted its course in space to execute a stable de-orbit maneuver and targeted South Pacific Ocean splash landing.

That precision maneuver contrasts with the 18,000-pound

Tiangong-1 prototype Chinese space station launched in 2011 that went rogue traveling at 17,000 miles per hour. The “Heavenly Palace 1” broke up in April 2018 and burned in the atmosphere as debris hurtled uncontrollably towards Earth.

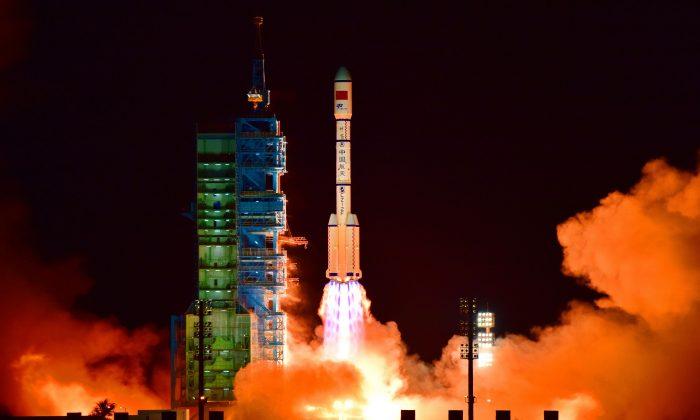

The 34-foot-long Tiangong-2 space station was launched from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center on September 15, 2016. A month later, Chinese astronauts (taikonauts) Jing Haipeng and Chen Dong piloted their

Shenzhou-11 spacecraft to successfully rendezvous and dock with the spacelab. The crew completed a record 33-day mission and safely returned to Siziwang Banner, Inner Mongolia on November 18, 2016.

The first two Tiangong space stations were designed as temporary orbital test vehicles to gain experience and prepare for the launch of the modular Tiangong-3. The 48,000-lb permanent space station will be 59.4 ft in length and have a width of 13.8 ft. Although substantially smaller than the 900,000-lb International Space Station (ISS) that measures 358 ft in length and 239 ft in width, ISS began construction in 1998 and is rapidly approaching its 2024 end of useful life.

The Tiangong-3

architecture includes a central module called “Tian He” scheduled for launch next year to provide quarters for three taikonauts. Two subsequent missions will each lift a 49-ft scientific laboratory that will graft to the orbiting Tain He. The Heavenly-3 modern design will provide about 25 percent of the ISS pressurized volume.

China also plans to launch a space telescope that will be similar to the U.S.

Hubble Space Telescope that was launched in 1990. The Chinese telescope will assume a similar orbit to the space station and be able to dock for ease of maintenance. But the Chinese telescope will be equipped with a 6-ft main mirror capable of a field of view 300 times greater than Hubble.

Although the Chinese regime advertises its space exploration as scientific, Enodo Economics calls space a “

virtually law-free domain” where China’s aspirations extend to establishing space colonies and to mining space for natural resources.

China has “rapidly become a front-rank space-faring power” engaged in a military contest with the U.S, according to Enodo. China is not subject to the

Outer Space Treaty signed in 1966 between the U.S. and the USSR that prohibits both nations from laying claim to celestial objects and from deploying weapons of mass destruction.

Enodo points out that the treaty is silent about space-based weapons and the use of terrestrial weapons against space-based facilities. With U.S. precision-guided weaponry dependent on global positioning satellites (GPS) for targeting, China demonstrated America’s satellite vulnerability in 2007 when it

launched a ballistic missile into space that successfully hit and destroyed one of its defunct low-earth-orbit satellites.

China is building its own duel use BeiDou Navigation Satellite System, as an alternative to GPS, and on June 25, 2019 successfully launched its

46th BDS satellite onboard a Long March 3B rocket from Xichang Satellite Launch Center.