Throughout his campaign, President-elect Donald Trump has been saying his immediate goal after taking office would be to deport the 2 million or so illegal immigrants with criminal records.

“Gang members, drug dealers, we have a lot of these people,” he said during the Nov. 13 “60 Minute” interview. “We are getting them out of our country or we are going to incarcerate.”

That pledge raises the issue of resources, though Trump hinted in a Time interview on Nov. 13 that he would take a softer position on Dreamers—people brought to the country illegally as children.

“We’re going to work something out that’s going to make people happy and proud,” he said. “They got brought here at a very young age, they’ve worked here, they’ve gone to school here. Some were good students. Some have wonderful jobs.”

That softer treatment, however, does not seem to include rescinding his campaign promise to scrap President Barack Obama’s executive orders that handed Dreamers work permits and protection from deportation.

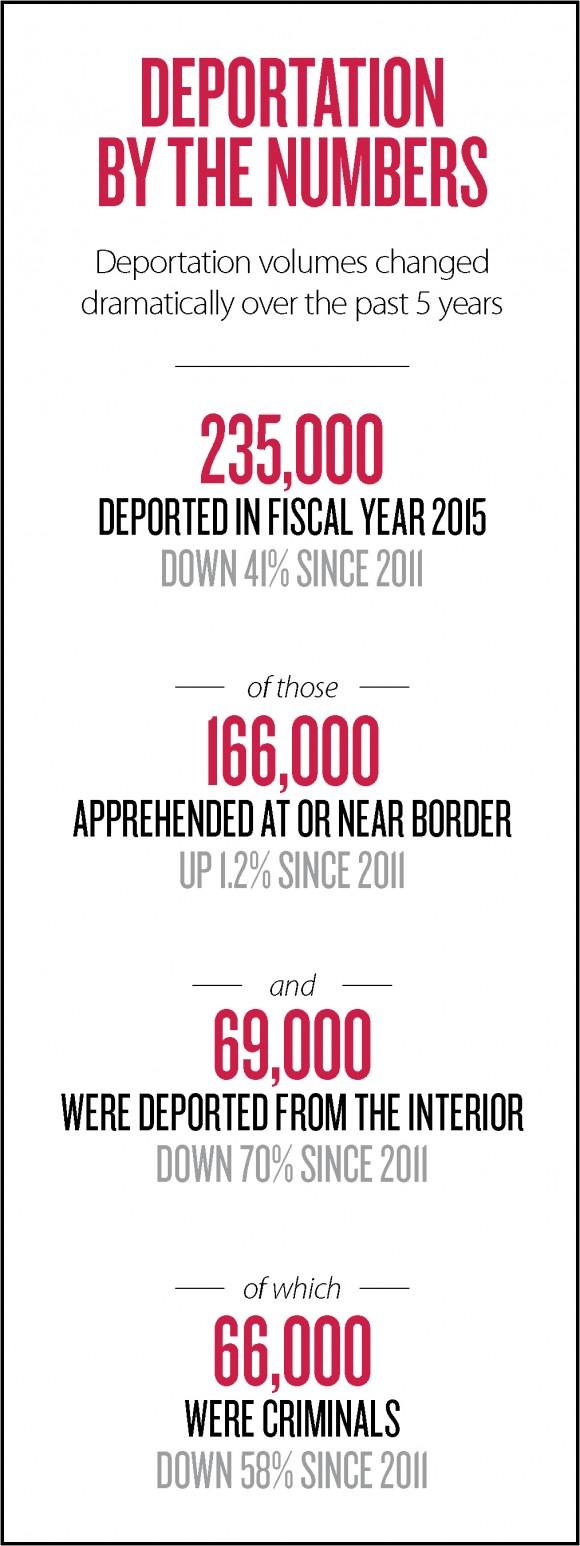

Whoever he decides to deport, Trump will face budgetary, logistical, and legislative constraints.

Courts and Detention Centers

Immigration courts, which decide the majority of deportation cases, are sinking under a backlog of over 526,000 cases (and counting), making people wait years for a court hearing.