The New York Times has ignored, downplayed, or misrepresented large swaths of human rights abuses in China, a new report says, arguing the paper’s sins against journalistic integrity have likely cost lives by skewing policy debate and propping up the regime’s dehumanizing propaganda.

Falun Gong, a spiritual practice consisting of slow-moving exercises and the study of teachings based on the tenets of truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance, was targeted for elimination by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1999, after a government survey indicated that more people practiced Falun Gong than belonged to the Party.

Despite its self-professed expertise in interpreting China developments, The New York Times’ coverage of the Falun Gong situation has been “shameful,” the report said.

“The impact of the Times’ distorted reporting and irresponsible treatment of Falun Gong practitioners as ‘unworthy victims’ has contributed to the impunity enjoyed by perpetrators and robbed their victims of vital international support, undoubtedly resulting in greater suffering and loss of life throughout Mainland China,” it states.

That’s not to say the paper has ignored the CCP’s human rights abuses writ large, the report noted. When it came to ethnic minorities such as Tibetans and Uyghurs, “The New York Times has devoted significant resources, attention, and column space to such accounts.”

But if the story involves Falun Gong, “the paper’s perspective is strikingly different,” it said.

Parroting Propaganda

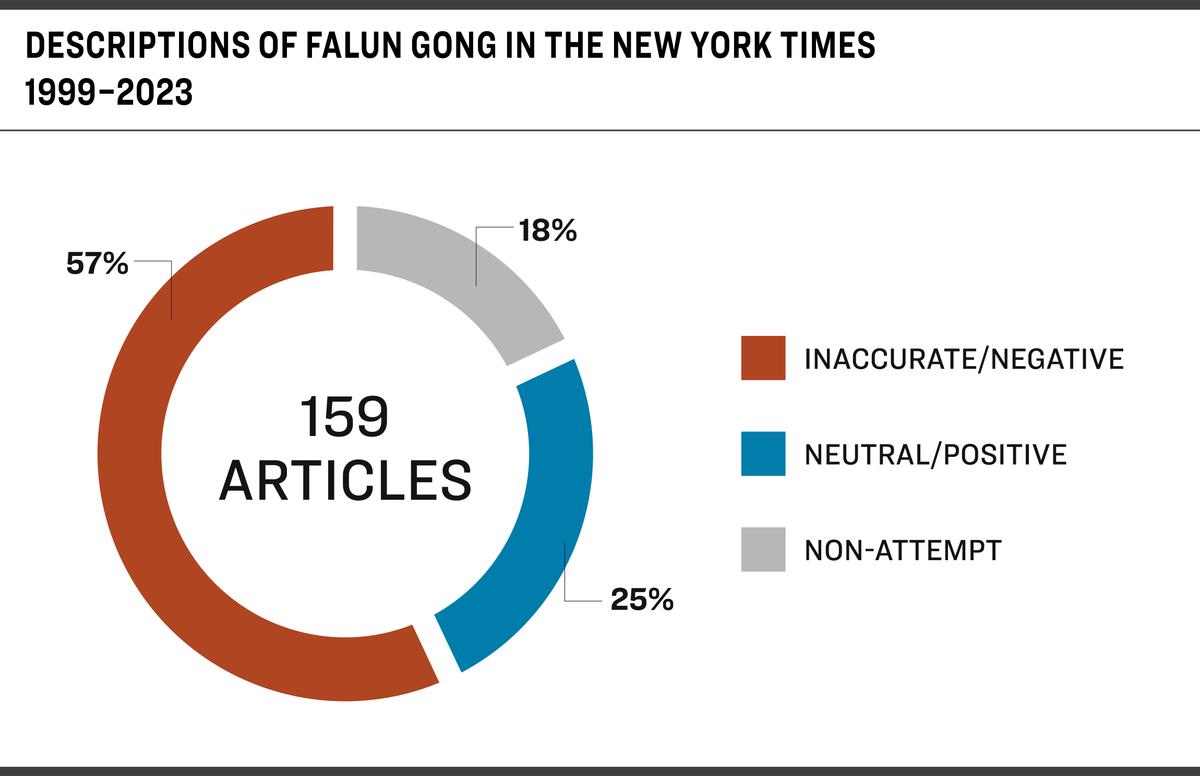

Over the past 25 years, the majority of The New York Times’ coverage of Falun Gong has been negative or inaccurate, with the common use of pejorative labels that echo the CCP anti-Falun Gong propaganda, the report said.In dozens of articles, the paper described Falun Gong as an “evil cult, an “evil sect,” a “cult,” or a “sect.”

In some cases, the paper noted that the “cult” label came from the CCP, but without further explanation of whether it’s true or not. In others, it ascribed the label in its own voice.

Scholars of Chinese religion, human rights researchers, and even journalists who did try to assess the veracity of the label concluded it’s unwarranted.

Ian Johnson, who authored a series of reports on Falun Gong for The Wall Street Journal in 2000, observed that the practice “didn’t meet many common definitions of a cult.”

“Its members marry outside the group, have outside friends, hold normal jobs, do not live isolated from society, do not believe that the world’s end is imminent and do not give significant amounts of money to the organization. Most importantly, suicide is not accepted, nor is physical violence,” he wrote.

“[Falun Gong] is at heart an apolitical, inward-oriented discipline, one aimed at cleansing oneself spiritually and improving one’s health.”

While other outlets, such as The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal, ran on-the-ground investigations into the persecution of Falun Gong, The New York Times’ early coverage was reactive and superficial by comparison, “relying almost entirely on statements from Chinese government sources or highly visible protests to drive its news coverage,” the FDIC said.

Repeating the regime’s propaganda is reckless and dangerous, the report said, highlighting an Amnesty International report saying that “the official campaign of public vilification of Falun Gong in the official Chinese press has created a climate of hatred against Falun Gong practitioners, which may be encouraging acts of violence against them.”

On the other hand, only about 3 percent of The New York Times’ articles on Falun Gong included the most basic description of the practice—its core tenets of truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance.

The report highlighted two notable exceptions to the paper’s trend of skewed reporting: Andrew Jacobs, who no longer covers China for the paper, authored a report in 2009 on the plight of several Falun Gong detainees and torture survivors and another one in 2013 after a note from a Chinese labor camp detainee was found in a Kmart product in the United States.

Lies About Numbers

Before the CCP’s persecution of Falun Gong began, multiple Western and Chinese media, including The Associated Press and The New York Times, reported that Falun Gong had 70 million to 100 million practitioners, generally attributing the numbers to the Chinese State Sports Administration. The Sports Administration conducted an extensive survey on Falun Gong in the late 1990s.Falun Gong practitioners themselves had no way to confirm the figures since the practice has no membership, the FDIC noted.

Once the persecution began, however, the CCP had an interest in portraying Falun Gong as marginal. It put forward a claim that it never had more than 2 million followers. The number was never backed by evidence.

The New York Times, however, started to uncritically use the 2 million figure. It went a step further, suggesting that the 70 million number was made up by Falun Gong, ignoring even its own reporting from just a few years prior, the FDIC report documented.

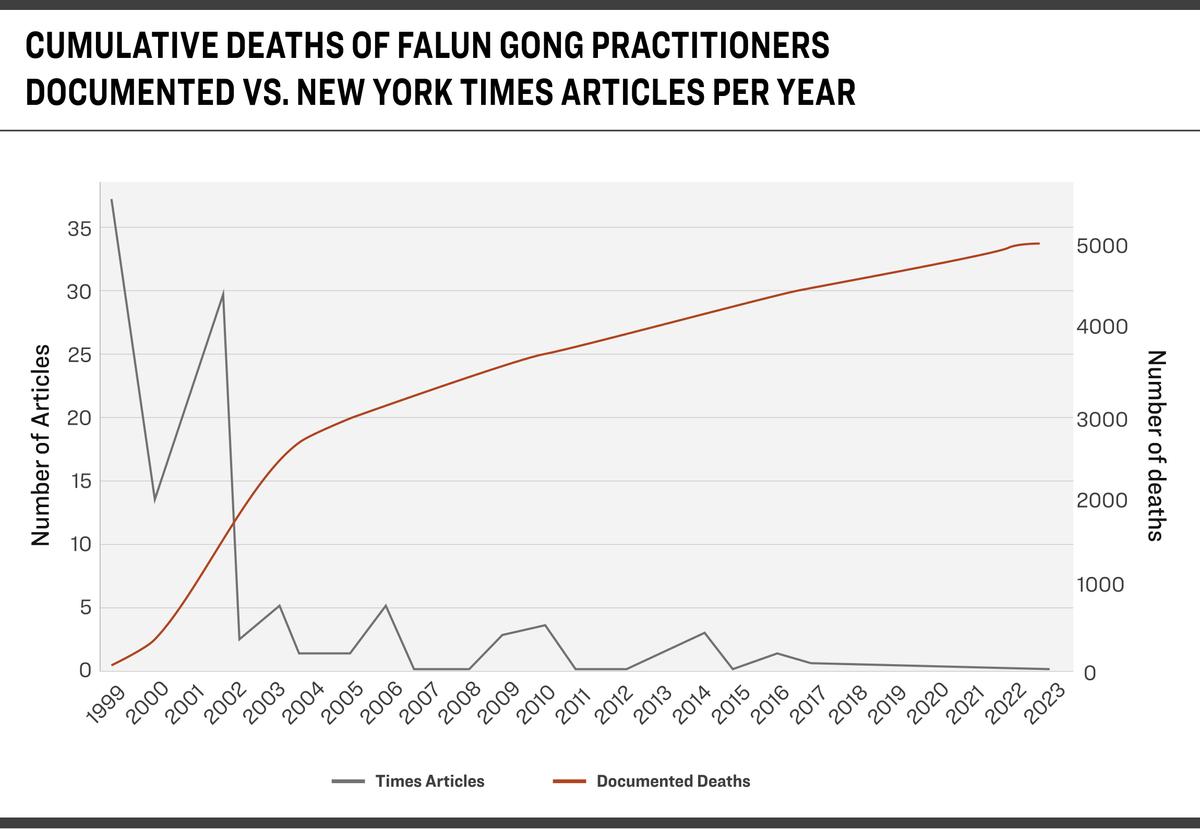

By 2002, The New York Times declared that Falun Gong had been “crushed” and thus was not a newsworthy subject. But that proved to be yet more CCP propaganda.

Washington-based nonprofit Freedom House estimated in 2017 that there were 7 million to 20 million Falun Gong practitioners in China.

“Despite a 17-year Chinese Communist Party (CCP) campaign to eradicate the spiritual group, millions of people in China continue to practice Falun Gong, including many individuals who took up the discipline after the repression began. This represents a striking failure of the CCP’s security apparatus,” it said.

As more evidence of the brutalities against Falun Gong amassed, The New York Times all but ignored it, according to the FDIC.

In 2016, New York Times reporter Didi Kirsten Tatlow met with several Chinese transplant doctors and overheard their conversation suggesting that prisoners of conscience were used in China as a source of organs for transplants. By that time, some human rights lawyers and researchers already had collated substantial evidence indicating that the CCP was indeed killing prisoners of conscience to fuel its booming transplant industry and that the primary target was practitioners of Falun Gong.

After authoring two articles on China’s organ transplant controversies that touched upon the issue of forced organ harvesting, Ms. Tatlow wanted to investigate the matter further but said she was blocked by her editors.

The tribunal concluded in June 2019 that “forced organ harvesting [had] been committed for years throughout China on a significant scale and that Falun Gong practitioners [had] been one—and probably the main—source of organ supply.”

The panel’s final judgment spurred a barrage of media reports in The Guardian, Reuters, Sky News, the New York Post, and dozens more.

“The New York Times, however, was silent,” the FDIC noted.

‘Hostile’

In recent years, the paper’s coverage of Falun Gong turned “openly hostile,” the FDIC said.In 2020, playing into the anti-racism fervor at the time, the paper included a claim that Falun Gong prohibited interracial marriage—an obvious falsehood, as interracial marriages are common among Falun Gong practitioners.

Articles also portrayed Falun Gong as “secretive,” “extreme,” and “dangerous” without bothering to substantiate the claims, the report said.

The brutality of the persecution, on the other hand, was downplayed as mere accusations. Falun Gong’s effort to counter it was characterized as a ”PR campaign.”

One 2020 article glossed over the decades of bloody repression with one sentence: “The group ... accuses [the CCP] of torturing Falun Gong practitioners and harvesting the organs of those executed.”

The persecution has in fact been extensively documented, including in dozens of reports by the United Nations, the U.S. State Department, Amnesty International, and Freedom House, the FDIC says.

Shen Yun has long been a thorn in Beijing’s side, by depicting the persecution of Falun Gong in some of its dance pieces and openly declaring its shows present “China before communism.”

Contrast

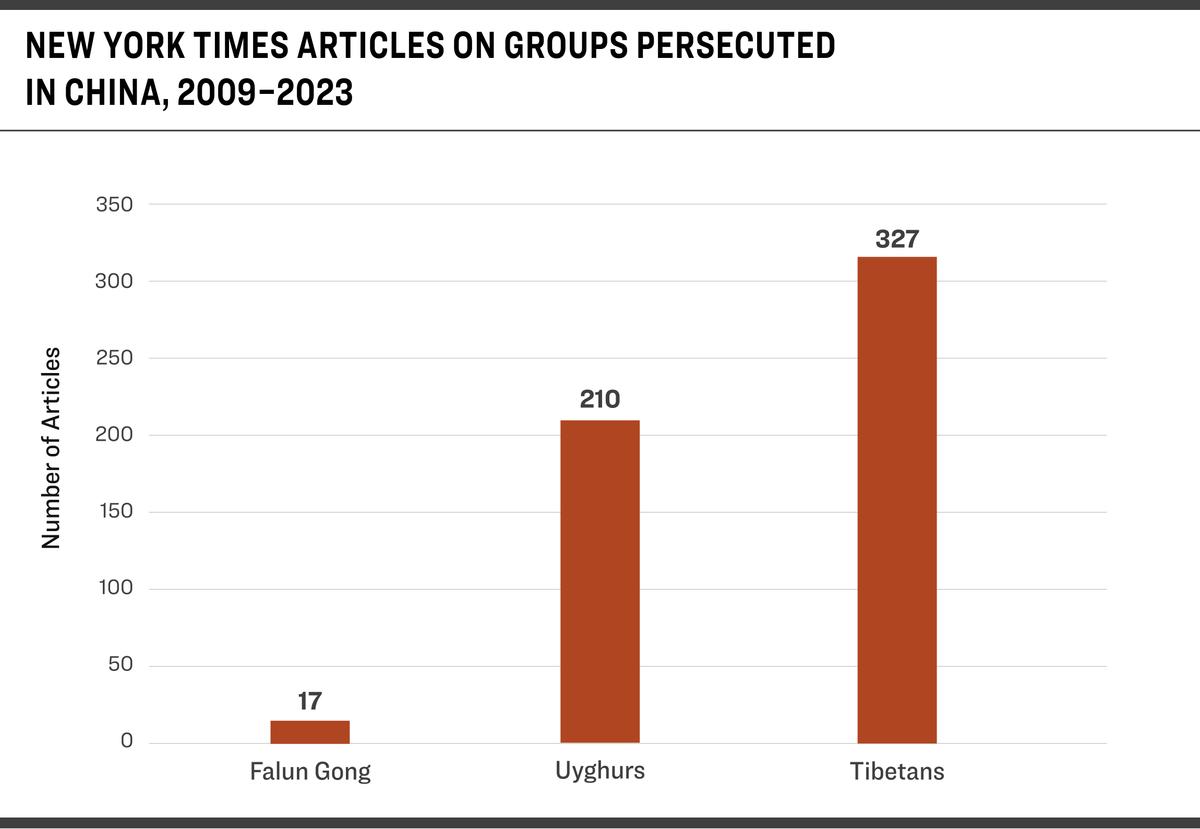

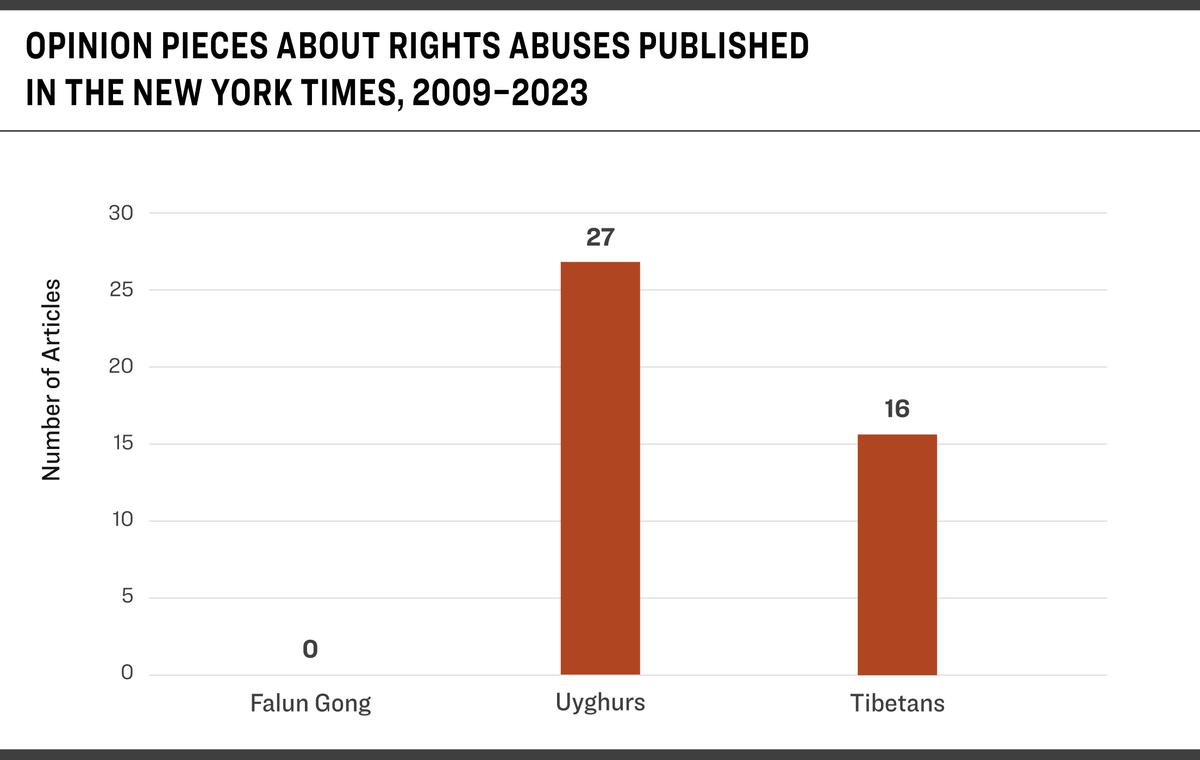

The New York Times’ treatment of Falun Gong stands in contrast to its handling of some other human rights abuses in China, particularly the persecution of Tibetans and the Uyghur Muslim minority in Xinjiang, the FDIC report says.Between 2009 and 2023, the paper ran more than 200 articles on the Uyghur issue, more than 300 on Tibet, and only 17 on Falun Gong.

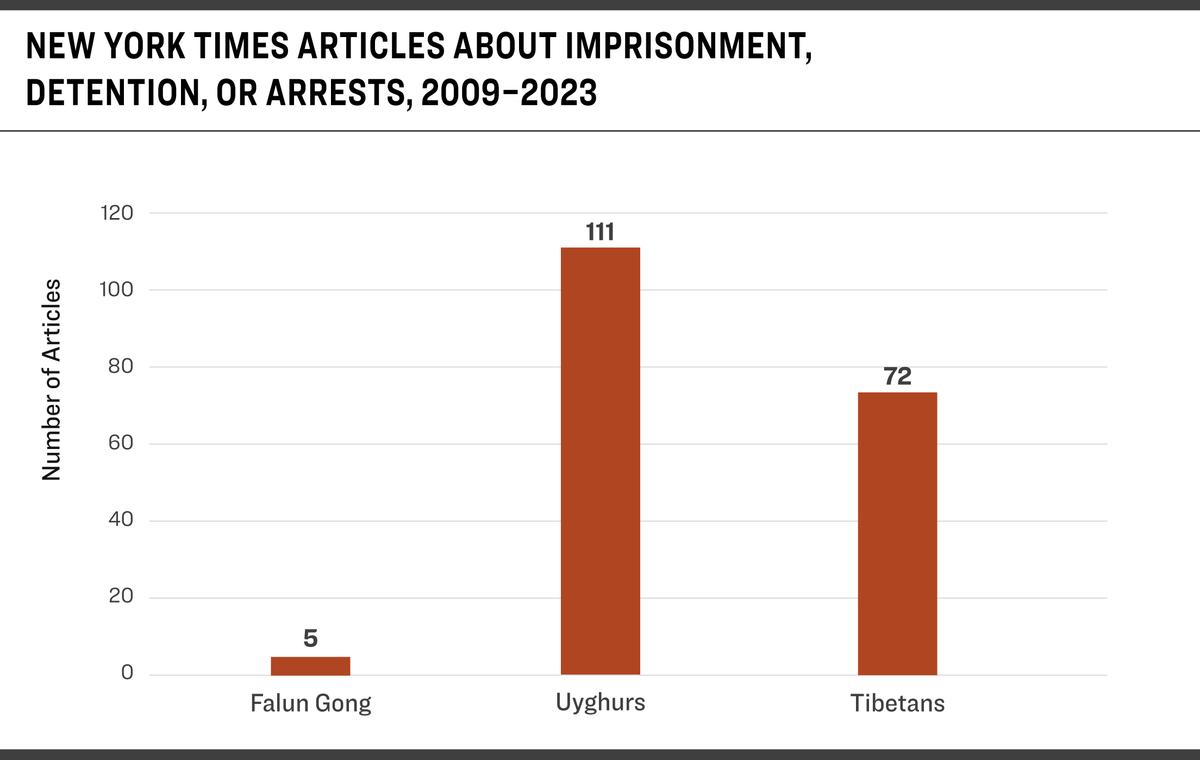

The quality of the coverage diverged dramatically, too. On Tibetans and Uyghurs, the paper extensively reported on the methods of repression, the conditions in detention facilities, and the stories of individual victims. The coverage was underscored by dozens of editorials or op-eds.

In the same time period, The New York Times ran no editorials, no op-eds, no columns—not even a letter to the editor—on the persecution of Falun Gong.

“This is not because no submission attempts were made,” the FDIC noted.

Stories on Tibetans and Uyghurs were “deserving of such coverage and international attention, while entailing risks for Times’ reporters and sources,” the report said.

“From this perspective, the contrast with the paper’s reporting on Falun Gong is stark. Even when the Times has reported on the persecution of Falun Gong, it has typically lacked the humanizing, personal focus evident in the above examples.”

New York Times spokeswoman Maria Case called the report’s conclusions “categorically false.”

“We have extensively and independently reported on the Falun Gong movement for more than two decades, including revealing accounts of abuse in Chinese labor camps, covering the debate around forced organ donation in China, and examining its expanding global influence, particularly in American media and politics,” she said via email.

The FDIC took issue with such a characterization.

“Our study carefully and thoroughly analyzed New York Times’ coverage, finding consistent use of inaccurate and pejorative labels that malign the practice and its believers and glaring gaps in coverage especially over the past decade,” said Levi Browde, the FDIC’s executive director. “That’s the reality of the paper’s coverage of Falun Gong, which is far from what might reasonably be called ‘extensive.’”

‘Virtue Signaling’

Despite repeated setbacks, The New York Times has put substantial effort into expanding its presence in China and penetrating the Chinese market.In 2001, The New York Times’ then-publisher, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., led a delegation of the paper’s writers and editors to Beijing, where they negotiated with the CCP to unblock the paper’s website within China. A few days after the newspaper published a flattering interview with then-CCP leader Jiang Zemin, the website was unblocked.

As The Washington Post reported, it was Jiang who personally launched the campaign to “eradicate” Falun Gong, against the wishes of other top CCP officials.

The New York Times’ website remained unblocked until 2012, when the paper irked the regime by running an article on the family wealth of China’s then-premier, Wen Jiabao.

Despite tightening media rules under current CCP leader Xi Jinping, the paper maintains offices in Beijing and Shanghai.

From the perspective of the paper’s vested interests in China, criticizing human rights abuses in the far-away Tibet or Xinjiang could be seen as relatively “safe,” according to Trevor Loudon, an expert on communist regimes.

“That’s virtue signaling—‘See we stand for human rights.’ But they would never do that with Falun Gong because that would really offend the CCP. The CCP would throw a fit over that,” he said.

While exposing abuses against Tibetans or Uyghurs sparks outrage overseas, it causes little instability domestically, Mr. Loudon said, because the ethnic minorities carry limited influence in China’s heartland.

Falun Gong, on the other hand, is “rooted in Chinese culture,” giving it an immediate appeal, he said.

“Chinese are not going to adopt Islam tomorrow. The Chinese are not going to adopt Tibetan Buddhism. But millions of Chinese have some sympathy for Falun Gong,” he said

It’s also easier for the CCP to use propaganda against ethnic minorities because it can assign them labels with clear political dimensions. In the case of Tibetans, the label is “separatists,” while Uyghurs are portrayed as “terrorists.”

Falun Gong practitioners, however, are mostly ordinary Chinese, scattered across the societal strata. Their only political demand has been for the regime to stop the persecution, Mr. Loudon noted.

“The Chinese can’t say that Falun Gong are separatists. They can’t say they’re terrorists. They can’t say they’re political, really. All they can say is that they’re weird or crazy,” he said.

If The New York Times were to extensively cover Falun Gong in a humanizing manner, it would directly assail the CCP propaganda wall, Mr. Loudon said. And that, he said, would challenge the regime’s legitimacy in the cultural realm.

“The CCP claims to be the inheritor of Chinese culture. Falun Gong is a rival to that and offers a very different vision,” he said.

‘What If’

The FDIC report concludes by asking several questions.“What if the Times had continued to tell the Falun Gong story—honestly, completely, and sympathetically, much like it does for Uighurs and Tibetans—to the world, even as accounts of atrocities piled up, and despite the CCP’s growing influence on the world’s stage?” it asks.

“How many Chinese families might not be separated? How many Falun Gong practitioners might still be alive?”

More broadly, the report posits, if the paper, with its unique “agenda setting” influence, covered the Falun Gong issue “to its full scale,” would that have prompted a more decisive international action “to counter these abuses and rein in the CCP’s excesses”?

“Would foreign companies and policymakers have awoken sooner to the risks of doing business with the CCP?” it asks.