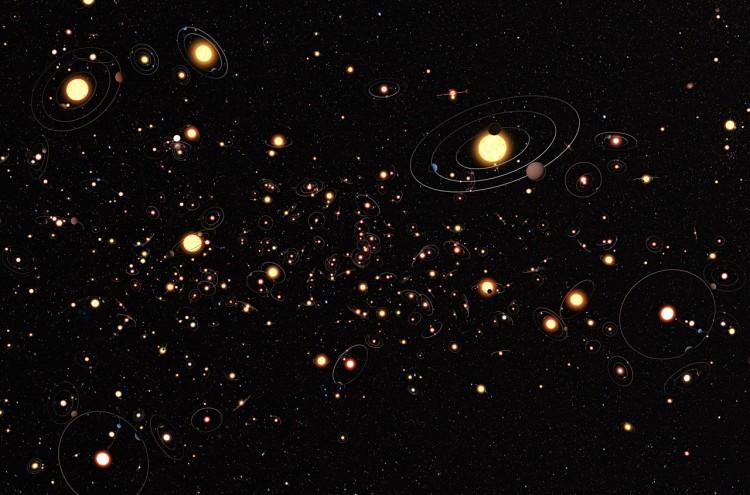

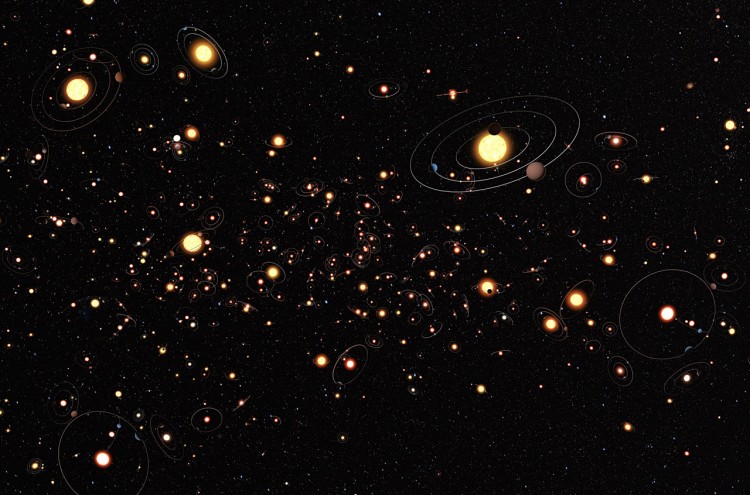

Extrasolar planets may be more abundant in our galaxy than previously thought, according to new research to be published in Nature on Jan. 12.

Using a technique called gravitational microlensing, astronomers from the European Southern Observatory (ESO) spent six years surveying millions of stars in the Milky Way and found that a star will probably be orbited by more than one planet.

Previously, two methods have been used to find exoplanets: detection of the planet’s gravitational pull on its host star, and observing the planet dimming its star’s light as it passes in front of it.

However, these techniques are best for locating planets that are massive or circling their stars closely. Consequently, many other exoplanets may be missed. In contrast, gravitational lensing can find planets with a wide range of masses, as well as those orbiting their suns at a distance.

“We have searched for evidence for exoplanets in six years of microlensing observations,” said study lead author Arnaud Cassan at France’s Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris in a press release. “Remarkably, these data show that planets are more common than stars in our galaxy.”

“We also found that lighter planets, such as super-Earths or cool Neptunes, must be more common than heavier ones.”

The gravitational field of a star can act as a lens, magnifying the brightness of a background star. If a planet is circling the lensing star, it adds to the magnifying effect. The scientists looked for this effect in data from the PLANET (Probing Lensing Anomalies NETwork) and OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) surveys.

Despite the technique’s power, its planet-hunting potential is limited by the coincidence of two factors: the chance that a background and lensing star will align correctly is very rare, and the planet’s orbit needs to be aligned too.

Three exoplanets were discovered during the six-year search—a super-Earth and two planets with masses similar to Neptune and Jupiter. This is a good outcome for such a fine-tuned technique, suggesting that the astronomers were either very lucky or exoplanets are commonplace in our galaxy.

In their statistical analysis, the scientists included seven other exoplanets, and the many non-detections from the observations, to determine that one in six of the stars surveyed hosts a Jupiter-like planet, half of them have Neptune-mass planets, and two-thirds have super-Earths.

“We used to think that the Earth might be unique in our galaxy,” concluded study co-lead author Daniel Kubas at the ESO in the release. “But now it seems that there are literally billions of planets with masses similar to Earth orbiting stars in the Milky Way.”