Several wildlife watchdog groups are calling for the rejection of a U.S. proposal to ban the international trade in polar bear products to be debated later this month in Qatar.

The U.S. government is seeking to convince 175 signatory countries to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) to join it in banning the trade of polar bear parts to protect populations from declining to dangerous levels.

The United States has asked CITES to change polar bears from Appendix II to Appendix I, making them an endangered species. This would effectively ban the commercial sale of hides and other products derived from the animals.

TRAFFIC, the international NGO that monitors the trade of wild animals and plants and their products, is opposing the proposed reclassification by the United States saying polar bears are not threatened by trade.

“The global population of polar bears is not small and has not undergone a marked decline in the recent past,” states a report by TRAFFIC. “Trade is not a significant threat to the species.”

A polar bear specialist group with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature has also said the bears are not threatened by trade at this time.

In addition, CITES has recommended rejecting the proposed ban, saying that for a ban to occur there has to be a marked decrease in polar bear populations.

Most of the world’s estimated 25,000 polar bears are in Canada. The 175 countries, including Canada, will vote on the U.S. proposal at the CITES meeting in Doha, Qatar, from March 13-25.

A U.S. ban on the import of polar bear products has been in place since May 2008 after the country elevated the animals to endangered species status. In other countries, however, polar bears are recognized as vulnerable, but not endangered.

Over half the world’s polar bear population can be found within the vast borders of Nunavut, Canada’s largest territory, and the possibility of a ban has officials there worried.

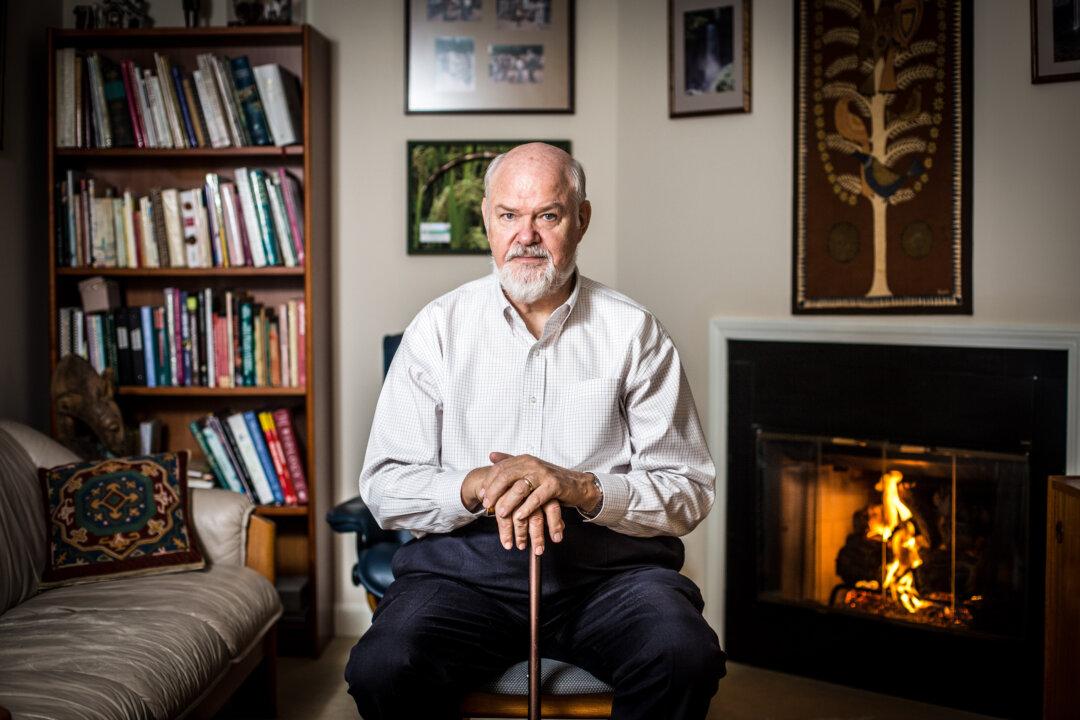

Gabriel Nirlungayuk, director of Wildlife for Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, a body that monitors and advocates for Inuit peoples on lands claims issues, is against the reclassification and says polar bear numbers are increasing rather than decreasing.

“We have seen a lot more polar bears than ever and science is agreeing with Inuit, so we’re a bit scratching our heads where the U.S. proposal is coming from,” says Nirlungayuk.

“Hunting is not a problem out here,” he says, adding that Nunavut works closely with area scientists and wildlife managers and complies with whatever decisions are made.

“OK, this is the allowable take and that’s what we follow, what’s according to science, so it’s a very small take and almost negligible,” says Nirlungayuk.

TRAFFIC and other groups say the biggest threat to polar bears is shrinking sea ice, which they attribute to climate change.

But Nirlungayuk says climate change is not a concern. Inuit traditional knowledge records periods of warming going back as far as 2,000 years, which the polar bears survived.

“The bears can survive in a warm climate,” he says. “Inuit don’t think that the polar bears are going to be disappearing so I hope that good heads will prevail in Qatar and vote against this proposal.”

Environmental and wildlife groups support a ban, viewing hunting as an additional threat the bears just don’t need. Canada’s scientist advisory body, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, has issued at least four reports advising the government to increase protections.

For now, Canada classifies polar bears as a species of “special concern.” So far, the Canadian government has been unwilling to up the level of this designation, opting for more discussion and cooperation with other countries with polar bear habitat, which includes the United States (Alaska), Russia, Greenland, and Norway.

In March 2009, the five countries concluded a polar bear summit with a joint declaration stating their concerns over climate change. They pledged to be good custodians of the polar bears and to use “traditional ecological knowledge in concert with western science” when making decisions.

According to Humane Society International, approximately 400 polar bear skins are traded worldwide annually, mostly to Japan from Canada.

The Inuit own exclusive bear hunting rights in Canada, and under a legal proviso the Canadian government allows hunting tickets—which were intended to allow traditional native food and clothing—to be sold to sport hunters. Wealthy trophy hunters pay as much as $25,000 to $40,000 to be able to hunt the bears.

Nirlungayuk says a hunting ban would create hardship for local hunters who have come to rely on polar bear hunting as a source of income in a difficult environment.

“There are no roads—almost everything has to be flown from the south and that’s very expensive, so what they do is offset some of the costs by hunting,” he says.

“All of the animal parts are utilized, and they share the meat with others, and then they are able to sell the hide in the open market to offset some of their costs.”

The U.S. government is seeking to convince 175 signatory countries to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) to join it in banning the trade of polar bear parts to protect populations from declining to dangerous levels.

The United States has asked CITES to change polar bears from Appendix II to Appendix I, making them an endangered species. This would effectively ban the commercial sale of hides and other products derived from the animals.

TRAFFIC, the international NGO that monitors the trade of wild animals and plants and their products, is opposing the proposed reclassification by the United States saying polar bears are not threatened by trade.

“The global population of polar bears is not small and has not undergone a marked decline in the recent past,” states a report by TRAFFIC. “Trade is not a significant threat to the species.”

A polar bear specialist group with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature has also said the bears are not threatened by trade at this time.

In addition, CITES has recommended rejecting the proposed ban, saying that for a ban to occur there has to be a marked decrease in polar bear populations.

Most of the world’s estimated 25,000 polar bears are in Canada. The 175 countries, including Canada, will vote on the U.S. proposal at the CITES meeting in Doha, Qatar, from March 13-25.

A U.S. ban on the import of polar bear products has been in place since May 2008 after the country elevated the animals to endangered species status. In other countries, however, polar bears are recognized as vulnerable, but not endangered.

Over half the world’s polar bear population can be found within the vast borders of Nunavut, Canada’s largest territory, and the possibility of a ban has officials there worried.

Gabriel Nirlungayuk, director of Wildlife for Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, a body that monitors and advocates for Inuit peoples on lands claims issues, is against the reclassification and says polar bear numbers are increasing rather than decreasing.

“We have seen a lot more polar bears than ever and science is agreeing with Inuit, so we’re a bit scratching our heads where the U.S. proposal is coming from,” says Nirlungayuk.

“Hunting is not a problem out here,” he says, adding that Nunavut works closely with area scientists and wildlife managers and complies with whatever decisions are made.

“OK, this is the allowable take and that’s what we follow, what’s according to science, so it’s a very small take and almost negligible,” says Nirlungayuk.

TRAFFIC and other groups say the biggest threat to polar bears is shrinking sea ice, which they attribute to climate change.

But Nirlungayuk says climate change is not a concern. Inuit traditional knowledge records periods of warming going back as far as 2,000 years, which the polar bears survived.

“The bears can survive in a warm climate,” he says. “Inuit don’t think that the polar bears are going to be disappearing so I hope that good heads will prevail in Qatar and vote against this proposal.”

Environmental and wildlife groups support a ban, viewing hunting as an additional threat the bears just don’t need. Canada’s scientist advisory body, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, has issued at least four reports advising the government to increase protections.

For now, Canada classifies polar bears as a species of “special concern.” So far, the Canadian government has been unwilling to up the level of this designation, opting for more discussion and cooperation with other countries with polar bear habitat, which includes the United States (Alaska), Russia, Greenland, and Norway.

In March 2009, the five countries concluded a polar bear summit with a joint declaration stating their concerns over climate change. They pledged to be good custodians of the polar bears and to use “traditional ecological knowledge in concert with western science” when making decisions.

According to Humane Society International, approximately 400 polar bear skins are traded worldwide annually, mostly to Japan from Canada.

The Inuit own exclusive bear hunting rights in Canada, and under a legal proviso the Canadian government allows hunting tickets—which were intended to allow traditional native food and clothing—to be sold to sport hunters. Wealthy trophy hunters pay as much as $25,000 to $40,000 to be able to hunt the bears.

Nirlungayuk says a hunting ban would create hardship for local hunters who have come to rely on polar bear hunting as a source of income in a difficult environment.

“There are no roads—almost everything has to be flown from the south and that’s very expensive, so what they do is offset some of the costs by hunting,” he says.

“All of the animal parts are utilized, and they share the meat with others, and then they are able to sell the hide in the open market to offset some of their costs.”