The Discount Model

The hallmarks of both Aldi and Lidl are low prices and no frills, attained by having a hyper-efficient business model. Supermarkets run by Aldi and Lidl place a premium on shopping efficiency. The stores are often around 20,000 square feet—about one-third smaller than typical U.S. supermarkets—and have fewer employees.Aldi stores in the United States have coin-operated shopping carts, do not provide free plastic bags, and employ no baggers. A common trait shared by both grocery stores is that many of their products are store brand rather than name brand. A small selection of specialty items, such as sporting goods, gardening supplies, and technology products, is available in each store.

Lidl’s U.S. arrival is a major test for new CEO Jesper Hojer, a 10-year Lidl veteran who previously ran the company’s Belgian operations. The company, which is private, is owned by Germany’s richest man, Dieter Schwarz.

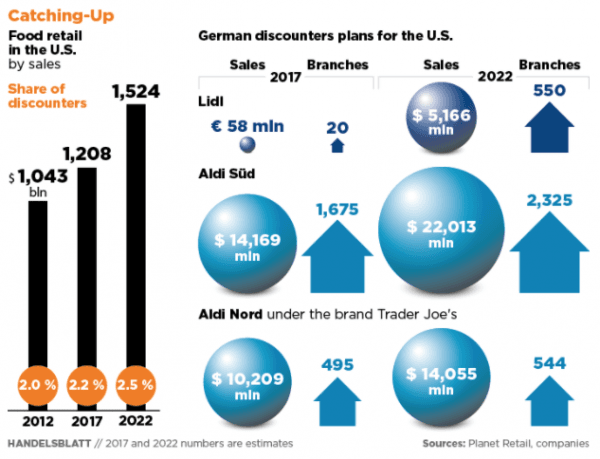

The size and scope of Lidl’s U.S. expansion strategy are unclear. But German publication Lebensmittel Zeitung speculated that Lidl wants to match Aldi’s success in the United States as quickly as possible. It has also signed up German supermodel Heidi Klum, who debuted a line of female clothing at the retailer in September.

While Aldi already has a 41-year head start in the United States, earlier this year it announced its own $5 billion investment in the country—$1.6 billion to renovate 1,300 stores by 2020, and another $3.4 billion to open 900 new stores by the end of 2022.

A Vulnerable Industry

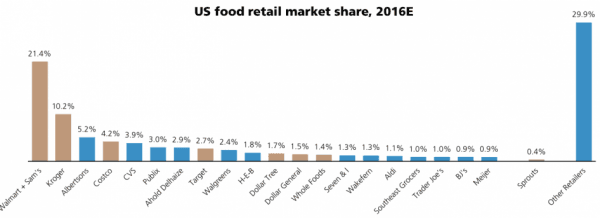

The food retail market in the United States is extremely fragmented. UBS estimates that the biggest single U.S. food retailer is Walmart, with a 21.4 percent market share, followed by Kroger at 10.2 percent, Albertson’s at 5.2 percent, and Costco at 4.2 percent. The majority of market share is shared among thousands of regional and specialty grocery retail chains.Traditional food retailers are facing challenges from online retailers as well as discounters.

According to market research firm YouGov, online grocery market sales will reach $30 billion in 2021, up from $12 billion in 2016.

While online retail emphasizes convenience and efficiency on the higher end of the market, discount retailers put additional pressure on prices and margins. YouGov reports that 42 percent of grocery shoppers it surveyed say that discount supermarkets are just as good as regular supermarkets. “Aldi and Lidl follow a pricing strategy that might change the customer’s perception of prices: good food for a good price might convince customers as it did already in other markets,” the YouGov report states.

In the long term, can Lidl and Aldi convince more U.S. shoppers that their private-label items are just as good as name-brand products? If history can be used as a guide, the answer is yes. Over the last 10 years, Lidl and Aldi have already disrupted the food retail industry in the UK, hurting the business of established players such as Tesco, Sainsbury, and Asda (a unit of Walmart).

In addition, the recent success of Trader Joe’s, which also sells a majority of private-label products at moderate prices, also offers a constructive blueprint. In fact, Trader Joe’s is owned by a company that spun off from Aldi in the 1960s.