Report: Disparity in Bank Branches

More than 825,000 New Yorkers do not have bank or credit union accounts.

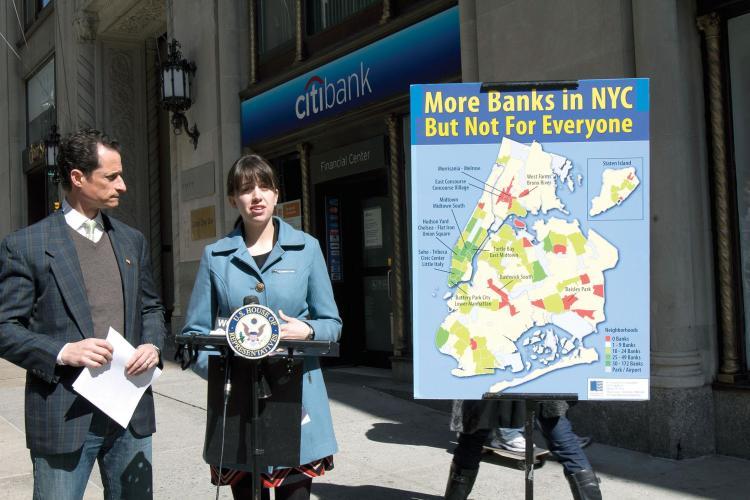

BANK ON IT: Rep. Anthony Weiner (L) and Megan Ahearn, Consumer Rights Organizer for the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), revealed the report on Sunday. Phoebe Zheng/The Epoch Times

|Updated: