A History of Repression

Gladney, who spent the last four decades researching China’s Muslim minority communities, and who has extensively traveled Xinjiang and Central Asia before being blacklisted by the CCP as a pro-Uyghur scholar in the early 2000’s, believes that Wang’s appointment will ensure a continuation of Chen’s harsh anti-Uyghur measures and a further hardening of China’s western border.“Chen Quanguo was successful from a Chinese [CCP] viewpoint in really consolidating power and authority,” Gladney said. “It was very restive in Tibet until he arrived in 2011. In 2016, when he came to Xinjiang, he brought a lot of these similar ideas.”

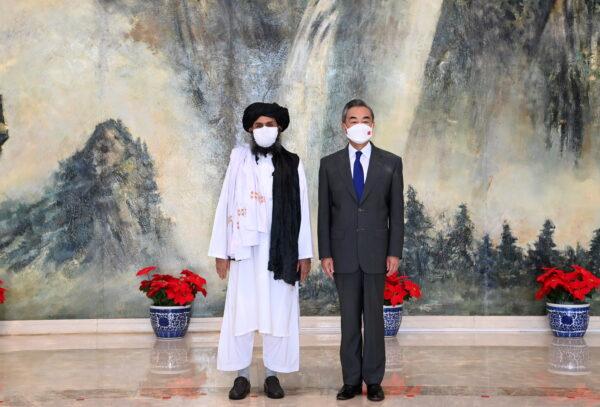

“Bringing in Wang Haijiang I think really reflects China’s concern about the restive regions around Xinjiang,” Gladney said. “Particularly Afghanistan now, with the withdrawal of the United States. It’s something that they’ve telegraphed, and China has always been worried about that border.”

The westernmost areas of Xinjiang share vast and desolate border areas with Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. Though the mountainous terrain makes it quite easy for the CCP to control major entryways to the country, the difficult topography means that there is always some porousness and a risk of infiltration by insurgents, particularly jihadis seeking to liberate the Uyghur homeland from the CCP. Further, the presence of Russian military elements in Tajikistan and radical Taliban elements in northeastern Afghanistan add a constant source of potential friction with China’s neighbors.

“In the military domain, Wang learned some valuable lessons in his capacity as deputy-commander of the Tibet Military District,” Lehberger said. “He was stationed on the contested Chinese border with India and Bhutan between 2016 and 2019. The lessons he learned then will now surely be applied in the XUAR at the Sino-Afghan border.”

Lehberger noted that Wang published several papers from his time in the Tibet Autonomous Region on the subject of training and fighting in mountainous regions and the types of defense structures to be used in such combat. Further, he said that Wang was commended for successfully coordinating the construction of high-altitude roads in border settlements in Doklam, a remote stretch of the Himalayas claimed by both China and Bhutan, which allowed the CCP to field troops in the area through the winter for the first time.

For effectively establishing the CCP’s permanent presence in the region, Wang was promoted to lieutenant general and made a delegate to the 13th National People’s Congress in 2017, the regime’s rubber-stamp legislature.

Lehberger also highlighted that Wang was something of a rarity among the CCP elite due to the fact that he had combat experience going back to China’s 1979 war with Vietnam.

Lehberger spoke to how the CCP has fostered increased antipathy from its Muslim population in recent years.

“During the last years, the Chinese regime has perfected a repressive apparatus and a catalogue of measures that are tailor-made for ethnic and Muslim minorities in the XUAR,” Lehberger said, “like forcing Muslim men to shave their beards and everyone to eat pork at daytime during the holy month of Ramadan.”

“What changed in Xinjiang I think was the rise in technology,” Gladney said. “Particularly digital surveillance technologies that Chen Quanguo managed to import, a lot of it from throughout the United States, Silicon Valley, and deploy to a level that nobody had ever imagined.”

![The Jieleixi No.13 village mosque with slogans “Love the [Chinese Communist] Party, Love China,” in Yangisar, south of Kashgar, in China's western Xinjiang region on June 4, 2019. (Greg Baker/AFP via Getty Images)](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimg.theepochtimes.com%2Fassets%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F05%2F10%2FGettyImages-1148084956-600x400.jpg&w=1200&q=75)

Following the incident, the CCP drastically centralized its authority and oversight over the everyday lives of the Uyghurs and others in the region.

“Terrorism made him [Xi] sort of support a radical crackdown,” Gladney said. “That’s when he brought in Chen Quanguo and now Chen Quanguo has brought in Wang Haijiang.”

Central Asia a ‘Pressure Cooker’

For now, Wang and Xinjiang are likely to be front and center in the CCP’s efforts to expand its influence and secure the Chinese interior. Feats that will be more fraught with peril than before following the fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban.“The truce between the CCP and the Taliban is a very tricky one for Beijing,” Kessler said. “There’s indications that they are going to recognize them as a more legitimate state actor but, at the same time, the Taliban still has ties to a lot of jihadist groups.”

Gladney too, expressed that a reactionary move to Islamic extremism that did not previously exist was being exacerbated by the CCP’s continued rights abuses against the Uyghurs. This is particularly true among the Uyghur diaspora, according to Gladney, who are increasingly looking to radical Islam as a means of liberating the Uyghurs they consider to be trapped in Xinjiang.

“China wants to make the Uyghurs more ‘Sinicized’, as Xi Jinping has said,” Gladney said. “This is probably driving them more strongly away from Chinese rule and building a great amount of resentment and anger, particularly in the diaspora.”

“Most of the violence and resentment was not inspired by radical Islam, or even independence. It was mostly inspired by a desire for greater human rights, greater freedom of expression,” Gladney added. “It drives these Uyghurs, who were not originally motivated by radical Islam or jihad, into the arms of those who are,” Gladney said.

In all, Gladney, Kessler and Lehberger agreed that the rising threat of extremism and unfolding events in Afghanistan meant that the likelihood of catastrophic violence in the region was increasing and, with it, the importance of Wang’s appointment in Xinjiang.

“I think it’s only a matter of time,” Gladney said. “Particularly in the diaspora, there’s many recent calls among the Uyghurs for violence, for independence. There’s been money flowing toward some of the more radical groups in central Asia, Turkey and south Asia.”

“This is like a pressure cooker situation. The more and more they [the CCP] tighten it, the more explosive will be the response.” Gladney added.

“I fear, with the fall of Kabul imminent, that the whole security situation is getting worse and for all involved,” Lehberger said.

“The situation with the U.S. and China, as well as Russia and Pakistan, it seems like it’s going to be very difficult to navigate from a diplomatic perspective without getting any bloodshed,” Kessler said. “It runs the risk of major conflict.”