Opinion

For Mother’s Day: Mother, You are in My Heart Forever

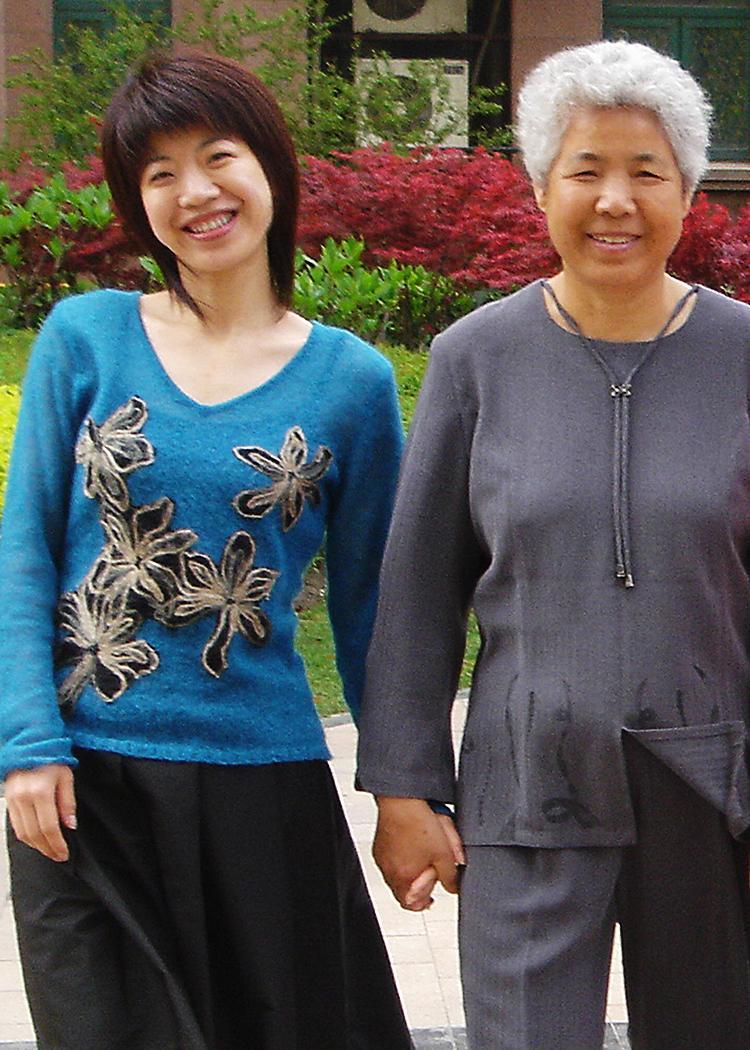

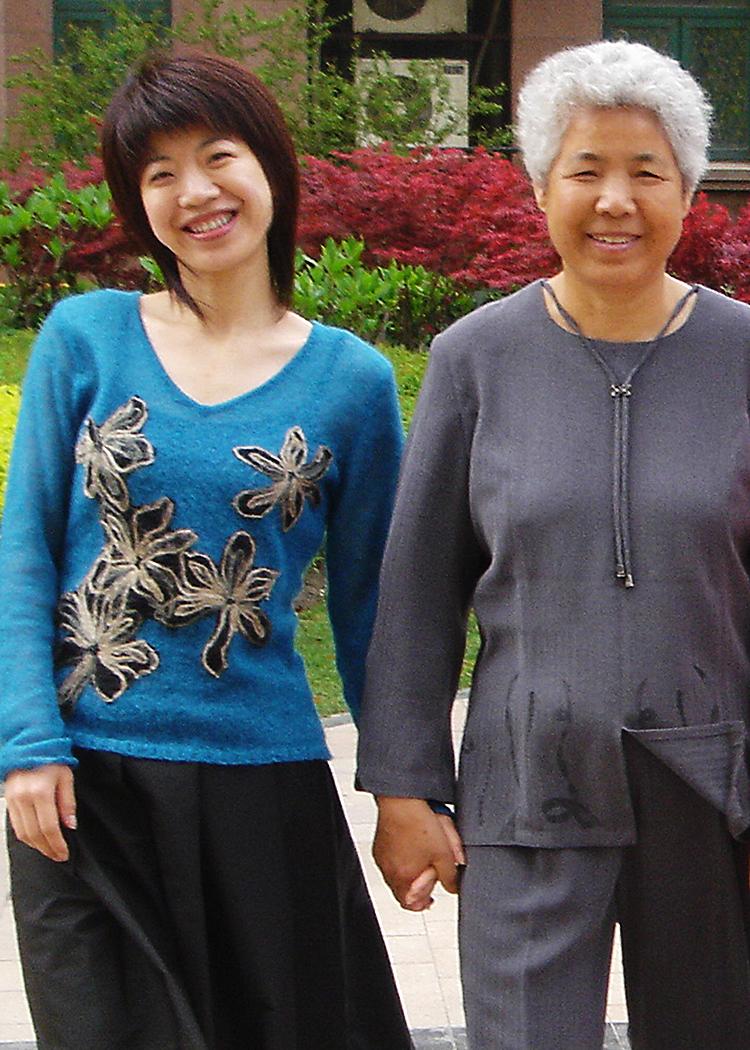

As Mother’s Day approaches, being in the U.S., I cannot help but think of my mother still living in China. She was a beauty, and while going through the black and white photos of her youth, I often joke as to why she did not pass her looks on to me.

Hui Yuan Gao (L) and her mother. Courtesy of Hui Yuan Gao

|Updated: