The last of Indonesia’s critically endangered Javan rhinoceroses have survived poachers, rapid deforestation and life in the shadow of one of the archipelago’s most active volcanoes. But an invasive plant is now posing a new threat to the world’s rarest species of rhino.

Once the most common of the Asian rhinoceroses, the Javan rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus) started its decline at least 3,000 years ago with the growth of human populations and increased hunting pressures. With its horn fetching $30,000 on the black market, poaching is considered the driver of much of its decline in modern times.

As few as 58 Javan rhinos exist in the world today, and the species is quite possibly the rarest large mammal on earth. All are found in one small population in Ujung Kulon — a sprawling 1,200-square-kilometer (463-square-mile) national park on the westernmost tip of West Java and the island of Panaitan. In addition the rhinos, the park is home to dozens of other mammals, more than 270 species of birds and 57 rare plant species.

But a single species of plant is threatening the park’s fragile ecosystem.

“The issue in Ujung Kulon is not deforestation — but an invasive species called the arenga palm,” said Elisabeth Purastuti, WWF’s Ujung Kulon leader.

Once covered in old-growth forest, the cataclysmic eruption of nearby Krakatoa in 1883 wiped out much of Ujung Kulon’s primary forest cover, creating a patchy network of secondary forest where the rhino thrived.

“Much of Ujung Kulon was secondary forest with a lot of gaps,” says Indonesian Rhino Foundation (YABI) executive director Widodo Ramono. A fact, he is quick to note, that was very favorable for the Javan rhino.

The gaps in plant life have also supported the proliferation of the arenga palm. Arenga obtusifolia, or “langkap” in Indonesian, is an invasive species that has also found a comfortable home in Ujung Kulon. The plant has demonstrated a voracious ability to thrive with precious little sunlight, spreading rapidly to the point where it covers as much as 60 percent of the national park on Java’s mainland. The arenga’s large arcing palms fronds cover the more fragile vegetation eaten by the Javan rhino, shading them from the sunlight.

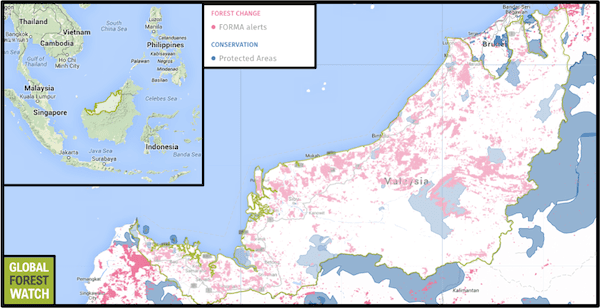

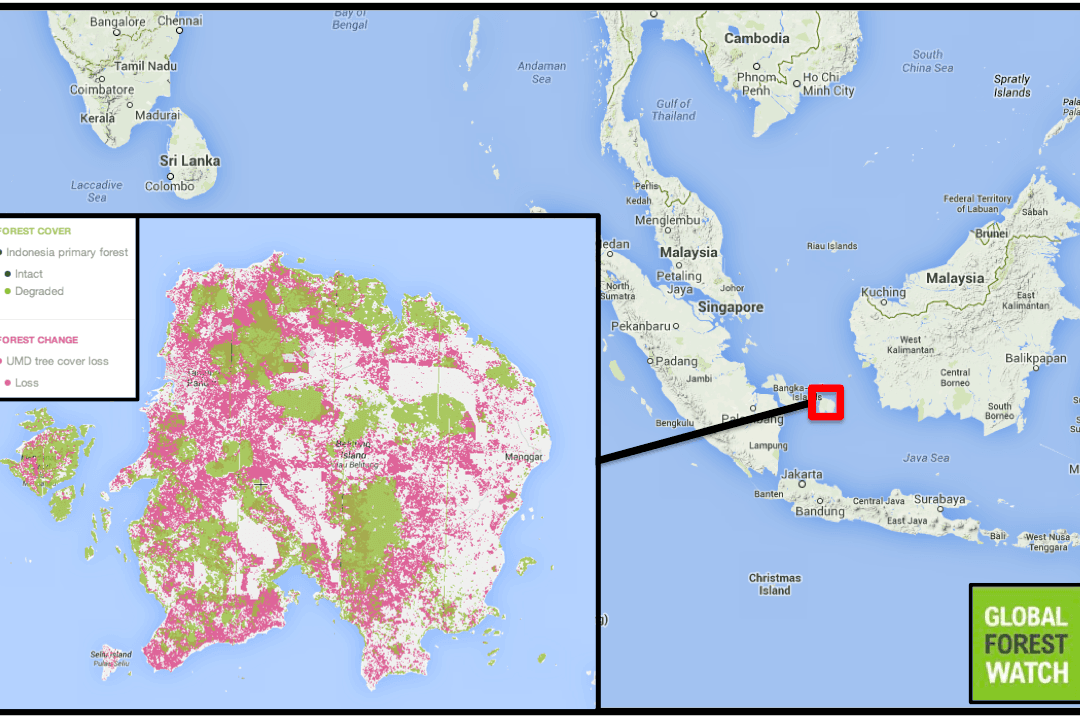

“When the canopy of the arenga palm closes, no other plants can grow,” Ramono said. This includes many of the rhino’s 250 food plants found in the park. The issue is unique to Indonesia, a country, according to data from Global Forest Watch data, which lost more than two million hectares of forest in 2012. Other species throughout the country, including the Sumatran tiger and orangutan, have been at the mercy of the country’s egregious deforestation practices.

The rate of deforestation in Java, according to Ministry of Forestry data, in 2010, was more than 7,000 hectares. According to Global Forest Watch, that rate increased to 18,000 hectares in 2011 — still a relatively small number compared to other parts of the country, but significant for forest-poor Java. And although, according to UNESCO’s website, the “poaching of the Javan Rhino has historically been the main management issue within the property,” the arenga palm has added a new challenge to this historically fluctuating population.

Ujung Kulon conservation chairman Mohammed Haryono told the Jakarta Globe in February that the park gained seven rhinos in 2013. But Ramono maintains that consistent population growth for the species has not been achieved yet.

“The population goes up and down,” he said. “There has been an upward trend, but it fluctuates and remains stagnant.”

The two organizations have set up cameras in the park to monitor the rhinos, and have also worked to control or eradicate the arenga palm within the park’s grounds.

YABI, which also works with Sumatran rhino populations in Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park and Way Kambas National Park, is conducting genetic research on the Javan rhino population. The foundation also works to empower locals living near the parks and explain the benefits of the areas.

“We are working to protect the rhinos,” Romano said.

Conservationists trying to save the Javan rhino maintain that saving the species from extinction remains an uphill battle. Perhaps the biggest risk for the species is that its one, tiny population is at risk of inbreeding depression, a condition in which rare, harmful genes become more common over time as relatives breed with each other. This can cause malformation, sterility, and death. Breeding females, of which there are precious few, need to be transferred to another possible habitat in order for the species to beat the odds over the longer term.

However, this will all be moot if the rhinos doesn’t have enough to eat. According to Purastuti, the WWF and YABI are working together to obtain a better understanding of the arenga palm’s affect on the rhino, and how to more effectively control it.

“We are conducting research on how to eradicate the arenga palm,” she said.

This article was originally written and posted by Ethan Harfenist, a correspondent for news.mongabay.com. For the original article and more information, please click HERE.