“I rarely tell people that I’m a shoemaker. In fact, I have an unspoken agreement with my friends when we go out for a drink together, that when people ask questions about what each of us does, we don’t say that I’m a shoemaker because otherwise, suddenly, I have five girls around me taking off their shoes in public and showing them to me.” So says Brendan Dwyer whose Melbourne CBD workshop is suspended in the 1920’s Nicholas Building with a pair of endearingly worn out iron cage elevators above a row of military precision fast food outlets in the shadow of St Paul’s Cathedral.

His nook harks back to an “ethos of 1920’s and 1960’s manufacturing where you could look at something and see how it was produced and I like that aspect of it,” he says.

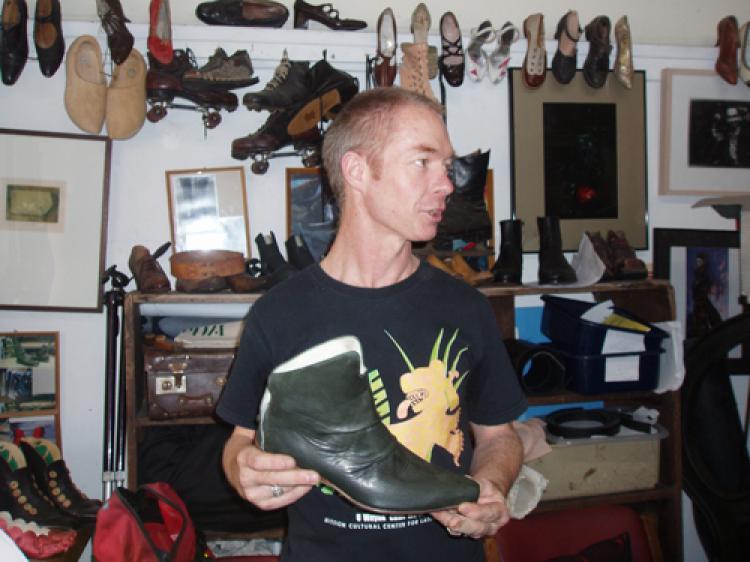

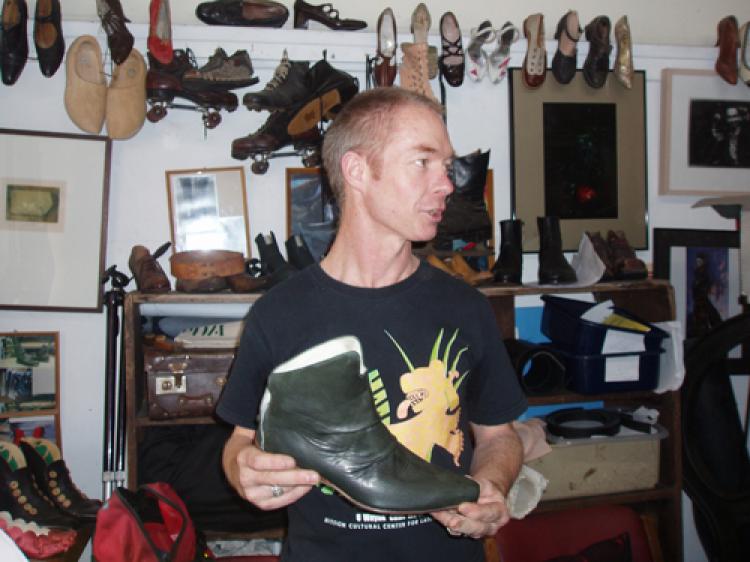

One foot into Brendan’s workshop and you’re already standing in the middle, surrounded by all things shoe business – rolled up coloured leather sheets, tools, lots of lasts (wooden foot moulds) to fit almost any shape foot and shoes, of course. All in all, a bit frustrating for a tactile person. There are pairs of liquorice black boots with creamy velvety lining; the sewing machine looks like some sort of gothic device whose function is far from obvious and that smell – leather, glue, old metal and dust.

Then, there’s the diminutive Brendan Dwyer himself dressed in the “form meets function” attire of a seasoned rave party-goer.

There’s a sense that meeting people is not an altogether comfortable undertaking for Brendan and that he’s somehow precariously suspended in the tension between the necessity of having to meet his clients and the freedom he gets to make what he loves.

“If you’re really involved in shoemaking, you take on the troubles of the world, as in, you have to listen to your clients and take that on, there’s a philosophical side as well. If you want to get the nitty-gritty of a client, to make them a pair of shoes that works for them, you have to get into them a little bit.”

His clientele ranges between 20 to 70 year olds and the price can be anywhere between $300 to $700 or more. This is a conservative cost, considering the 280 processes involved in making a pair of shoes and that mass produced, standard fit designer footwear can be bought for $1400 upwards, minus the personal touch and involvement.

Once upon a time, Melbourne was the shoemaking capital of Australia with factories everywhere. Now all have been moved overseas due to the cost of labour, but in Brendan’s opinion, this was avoidable. He explains: “One of the biggest failings of the Melbourne shoe industry, when I watched it go into decline in the 80s and 90s, was that most of the manufacturers, when there was a flood of cheaper imports, tried to match them by making cheap shoes, rather than pursuing quality shoes.”

There are a few scattered shoemakers, but it is clearly a dying craft. Brendan Dwyer’s niche is relatively narrow and sustained not just by his private clients, but also by the commissions he receives from Victoria Opera, the Malthouse Theatre, occasional films and footwear for acrobats in Circus Oz.

And no, the global economic crisis did not affect his business, with most clients becoming repeat customers.

It’s hard to imagine that anyone would not like anything that Brendan Dwyer makes, but he tells of a couple of instances when clients have returned the shoes because they either elicited too much response from the public, as in, too many people wanted to talk to them about their shoes or they just had bad responses from their partners.

“People want shoes that look ‘them’. They don’t want the shoes to be the object for people to look at. It has to be the whole thing,” Brendan says.

“I made shoes for a girl that everybody loved and she came back and she cried because they were funky, but she wasn’t funky. She wanted a very classic 1920’s shoe. That’s a case of people not really figuring out the breadth of what I can make or missing something about what and how I make shoes.”

And, just in case you’re thinking of ordering a pair of shoes from him, the “I’ve got the money, you’ve got the goods” motto does not apply in the Brendan Dwyer workshop.

“I’ve cancelled orders on customers,” he explains. “I’ve said: ‘Look, we’re not getting along here, the fruition is not going to happen.’ Some people come to me and say: ‘Well, you’re a craftsperson, you can make this,’ and other people come to me as an artisan and say: ‘You have to have the passion to make this for me,’ and if the passion’s not there, then the passion’s not there. The money doesn’t pay for passion. You can buy passion out there on the street with money, but not here.”

So do your research and when he asks you what you have in mind, you can say something like “a pair of liquorice black Argentinean tango shoes with the most violent emerald green lining, please.”