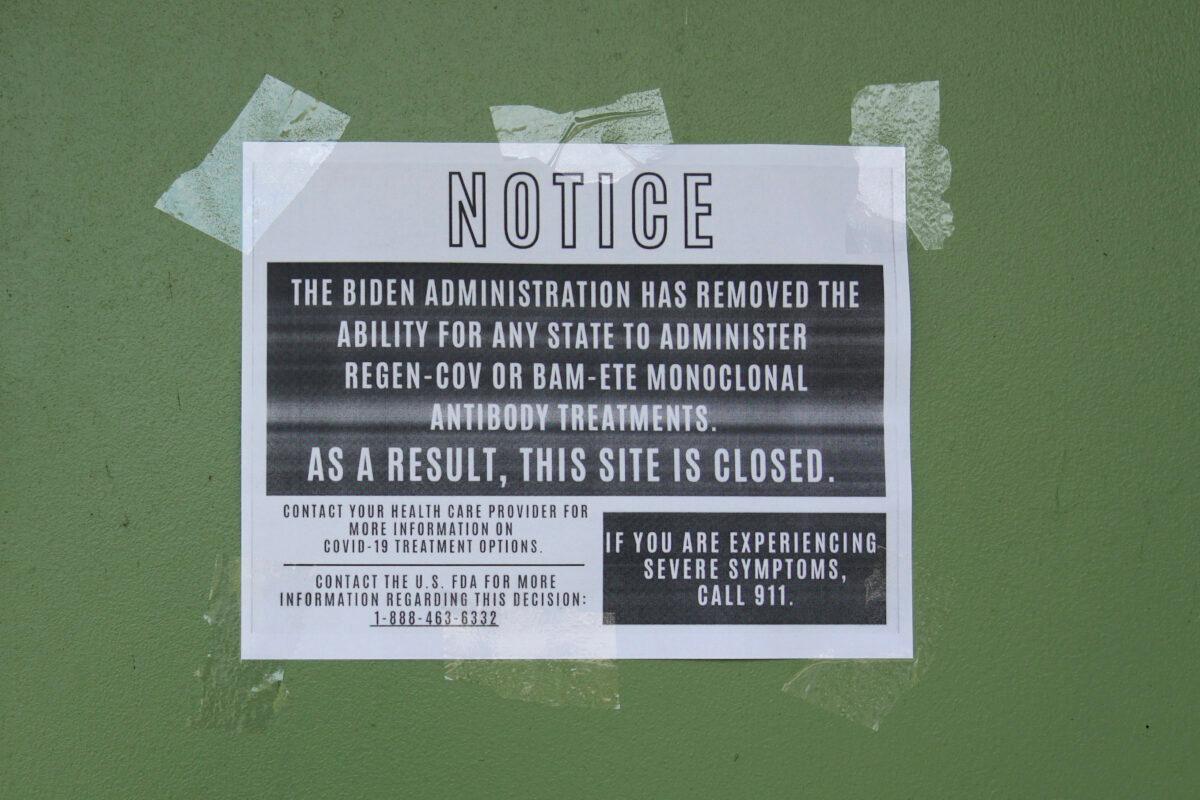

The Food and Drug Administration’s decision to effectively revoke emergency use authorization for two monoclonal antibody treatments has left experts divided, with some calling it the right move and others asserting it shouldn’t have been done.

Federal officials have defended the action.

“We have a really robust amount of scientific data, including from the companies themselves. Don’t forget, they discovered these monocolonals, and they set up assays to monitor them, and they also say these monoclonals don’t neutralize Omicron,” Woodcock said.

A Lilly spokesperson told The Epoch Times earlier this week that the company backed the FDA’s decision, while both companies have said they’re working on revamped monoclonals that work against the variant.

Studies

Apart from the data the FDA generated, the agency indirectly cited two studies that were utilized by the NIH panel.

Neither have been peer-reviewed.

The CCP virus causes the disease COVID-19.

The corresponding authors didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“It is clear from our work and from that of other teams that bamlanivimab/etesevimab and REGEN-COV lost any neutralization activity against Omicron in cell culture systems. It is thus highly unlikely that they might have any protective role in patients,” Olivier Schwartz, one of the authors, told The Epoch Times in an email, referring to the two treatments the FDA banned for now.

A third study, which was peer-reviewed and which U.S. officials didn’t reference, found certain monoclonal antibodies didn’t perform well against a cell isolate of Omicron, including the Regeneron and Eli Lilly treatments.

Dr. Michael Diamond, one of the authors, who consults for Vir Biotechnology and is on the scientific advisory board of Moderna, a COVID-19 vaccine maker, said he agreed with the FDA’s decision.

“The antibodies in all likelihood will not work—they lose all neutralizing activity (our data) and binding activity (others),” he told The Epoch Times via email.

The researchers wrote in the paper that “despite observing differences in neutralizing activity with certain mAbs, it remains to be determined how this finding translates into effects on clinical protection against B.1.1.529.”

Critics have pointed out that many of the authors of two of the studies either work for Vir Biotechnology, which has partnered with GlaxoSmithKline to make a monoclonal treatment called sotrovimab, or have other links to the company.

The GlaxoSmithKline monoclonal was said to be one of the only treatments of its kind to retain strong effectiveness against Omicron and has not had its emergency use authorization changed or revoked.

“You’re knocking out your competitors here. No one’s really talking about that, but it’s right there in the disclosures,” Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, said this week.

Diamond responded to the criticism, noting that he and other researchers with or linked to Vir have in the past published studies showing the effectiveness of the drugs.

“Our findings are now supported by work of SEVERAL other groups who found essentially the same thing,” Diamond wrote, “REGN and LILLY completely lose activity; AZ loses a lot but still retains some; VIR is much less affected.” AZ refers to AstraZeneca.

Dr. Benjamin Wilfond, professor and chief of the Division of Bioethics in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine, told The Epoch Times that research often involves a range of conflicts of interests, making disclosures important.

People reading the papers “ can make their own assessment of what to do with the information,” he said.

Companies often fund studies of their products and, less often, study their own product in comparison with rival products, he added.

Pushback

Some other experts disagree, saying the handful of studies weren’t enough to pull treatments that have, prior to Omicron, shown high effectiveness against hospitalization.On the one hand, the studies on cells suggest the treatments might not perform as well against Omicron, Dr. Kenneth Sheppke, the Florida Department of Health’s deputy secretary, told a roundtable in Miami on Jan. 26. On the other hand, “we have real-world experience in humans, where we see really excellent outcomes,” he said.

“Those two pieces of data conflict. And rather than saying, ‘well, then let’s just stop doing it,’ I think we need a third piece of data as the tiebreaker, which is, let’s do a formal study on humans to see if it works or not. Maybe it will, maybe it won’t work on humans, but I think that’s been a missing data piece,” he added.

Dr. David Farcy, chairman of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center, said he and others at the center administered the Regeneron treatment to 1,000 high-risk patients in recent weeks, and less than 5 percent required hospitalization.

Farcy said the center has trials underway to verify whether the monoclonals work against Omicron.

Dr. Dwight Reynolds, medical director and owner of Centers for Health Promotion, said he was upset when he heard of the FDA’s action because he’s used Regeneron’s drug on 200 patients in the past two weeks and none reported any problems afterward.

While federal data indicates the overwhelming majority of current COVID-19 cases are caused by Omicron, a percentage are still caused by Delta, the previous dominant strain, roundtable participants noted.

There’s no quick way at present to determine which strain has infected people.

“I think the FDA, it was a premature decision to remove it,” Farcy said.