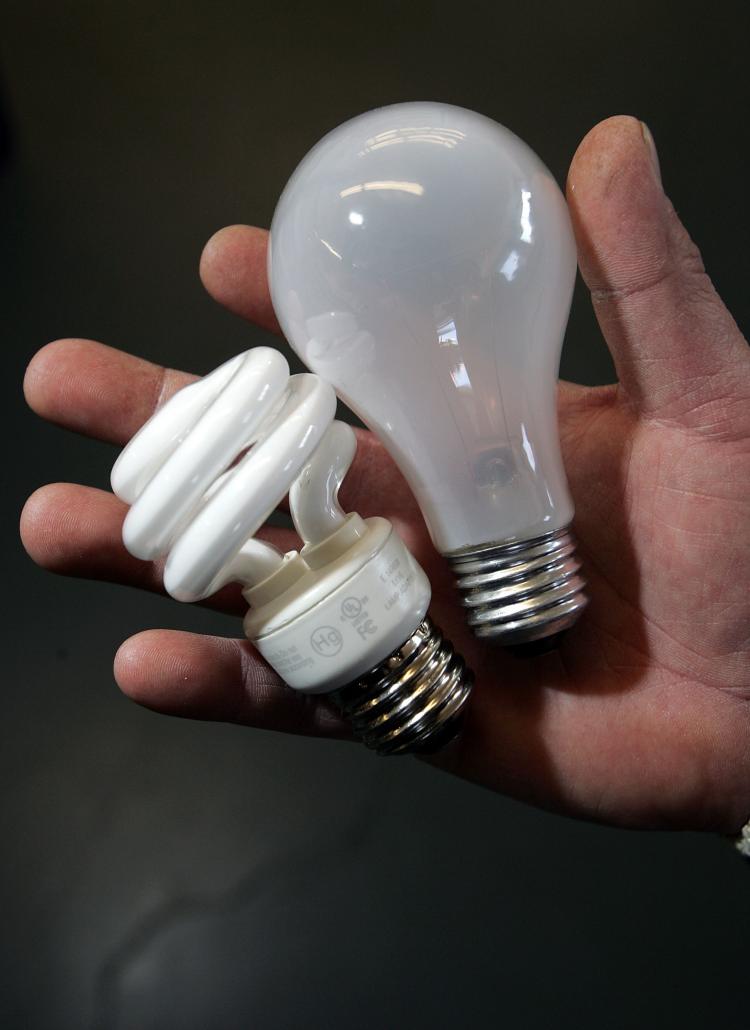

They contain mercury, cannot be easily recycled, and their production causes environmental damage, yet many of the world’s governments say compact flourescent lights (CFL) must replace the traditional incandescent bulbs within the next few years.

Over 40 countries, led by Australia and including Canada and the United States, have begun a phase-out of incandescent bulbs. Most plan to ban the sale of incandescents by 2011-2012 and legislate a switch to CFLs.

CFLs use only 75 percent of the energy needed to power standard bulbs, thereby lessening greenhouse gases, greatly reducing lighting energy demand, and saving money on residential electricity bills.

But the odd-shaped bulbs, which come in a range of styles and types, have been receiving some bad press of late, with critics saying the lights have to be kept on longer to run efficiently, are not environmentally friendly, and pose serious health risks for certain individuals.

Health Canada launched a study in December over concerns that the energy-saving light bulbs emit ultraviolet radiation. Preliminary results will be released in late summer or early fall.

In the U.K., the Health Protection Agency announced in October that, in close proximity, CFLs emit UV rays similar to outdoor exposure levels on a sunny summer day. When the light is more than 30 centimetres (one foot) away or if it’s encased in a glass covering there is no danger, the agency said.

The more intense light emitted by CFLs has been accused by Spectrum, an alliance of charities working with people with light sensitive conditions in the U.K., of triggering migraine headaches and skin rashes, and aggravating existing conditions such as lupus, eye disorders and epilepsy.

In response to the U.K. government’s decision to ban regular light bulbs by 2011, Spectrum is running a campaign to raise awareness of the health impacts of CFLs. They claim as many as 340,000 people could be affected.

Meanwhile, Britons are stockpiling traditional bulbs. Stores such as John Lewis, Sainsbury’s and Homebase are reporting a shortage of 100 watt bulbs as consumers stock up before they are removed from the shelves for good.

Other complaints about CFLs are that most don’t work with dimmer switches or electronically triggered security lights, they are too dim for reading and give off a colder type of light, they don’t fit most lampshades, take time to warm up, and many are not usable in freezers, ovens or microwaves because these are either too cold or too hot for them to function.

Then there’s the thorny issue mercury. The five milligrams of mercury—an amount as small as the tip of a pen—that each compact fluorescent contains is in vapour form, which means it disperses through the air if a CFL is broken.

“When mercury is in vapour form and you inhale it, it can get into the brain very easily. If you’re pregnant it gets into the placenta, it gets into mother’s milk. So there’s a real problem with this form of mercury,” says Magda Havas, associate professor of environmental and resource studies at Trent University.

Both Natural Resources Canada and the Environmental Protection Agency in the U.S. advise that if a CFL is broken, the room should be cleared of people and pets and aired out immediately, and that the glass fragments should not be vacuumed.

Havas says this is because the vapour will remain in the vacuum and re-distribute it each time the vacuum is used.

Havas, who teaches and does research on the biological effects of electromagnetic fields, dirty electricity, and electrical hypersensitivity, says the Canadian government, for one, did not do its homework before jumping on the CFL bandwagon.

“Has the government done enough research—definitely not. They just accepted this as something that was the next best thing. They’ve just gone with it and I think it was a mistake.”

Theo Paradise-Hirst is head of lighting design for U.K.-based Max Fordham, an award-winning company of design technologists who specialize in energy efficient and sustainable systems for building services and the wider environment.

Paradise-Hirst says there are many “forgotten costs” in the production of CFLs, the vast majority of which are manufactured in China.

“The processes, waste and by-products created by manufacturing CFLs are hideous. I’ve been to the Far East and seen the factories where these lamps are produced, and the waste toxins and by-products are alarming.”

He says that because many CFLs are produced in countries where “environmental issues and human rights are just ignored,” continuing to import them is “offsetting our environmental responsibility.”

“By sourcing products in this way we are transferring our environmental responsibilities to unaccountable communities for commercial gain.”

Although some stores such as Canadian Tire, Home Depot and Ikea accept spent CFLs for recycling, both Paradise-Hirst and Havas fear that many will end up in landfills, leaching mercury and other chemicals into the environment.

Paradise-Hirst also says the disposal process of CFLs is “very complex and energy-consuming.”

However, the green movement holds that the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions by a projected five million tons a year offsets any shortcomings CFLs might have. Keith Stewart, a climate change analyst with the World Wildlife Fund, thinks CFLs have their place.

Stewart says despite the mercury content, “CFLs are still a good option because you can capture that mercury and reuse it, whereas once it goes up in a coal stack there’s nothing you can do about it. More mercury is released into the environment from burning coal for the extra energy needed to run a regular light bulb than is in a CFL.”

He says CFLs have improved greatly in the last 10 years and predicts that by 2012 there will be other options available.

Havas says a study in which she participated to be released later this year found that a far more efficient alternative to CFLs are light emitting diodes (LEDs).

To give the same amount of light as a 60 watt traditional bulb, a CFL would use 15 watts while LEDs use only about three or four watts and don’t contain mercury, she says. However, LEDs are new to the market and still quite pricey, just as CFLs were a few years ago.

Stewart says there are silicon-based bulbs currently being pioneered in Canada that also contain no mercury and use less energy than either CFLs or LEDs.

Because flourescents as a technology have been around since the turn of the last century, Paradise-Hirst believes the time has come to support new technologies, including LEDs, the plasma lamp invented by Nikola Tesla, and an environmentally friendly, high-energy efficiency bulb produced by Ceravision which uses microwave technology.

In the meantime, we should simply dim the lights.

“We need to examine our energy usage more thoughtfully,” he says. “If all the street lights around the globe were dimmed by 50 per cent after 2:00 a.m., that would save significant amounts of energy.”