House prices in China can fall fast, especially around the Chinese New Year, just to quickly recover soon after. We saw this in 2011 and 2012. This year seems to be different though, and not in a good way.

On March 17, the National Bureau of Statistics announced prices in 70 of China’s major cities dropped 5.7 percent on average in February 2015 compared to a year earlier. This is the sixth consecutive decline on record and January was also bad with minus 5.1 percent.

According to private surveys, units sold in 48 cities declined by 10.9 percent over the year as government revenue from land sales cratered 36.2 percent in the first two months of the year, according to Shanghai Daily.

In a nutshell, people aren’t buying from developers and developers aren’t buying more land from the government. This is a big deal in a country where real estate contributes 20 percent to GDP and houses make up the bulk of the people’s savings.

According to a 2013 survey by economist Gan Li, professor at Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in Chengdu, Sichuan, and at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas, 65 percent of China’s household wealth is invested in real estate.

He told Bloomberg in the beginning of 2014, “Existing housing stock is sufficient for every household to own one home, and we are supplying about 15 million new units a year. The housing bubble has to burst. No one knows when.”

Developers the Biggest Debtors

Despite the similarity of the price declines between the early subprime crisis days and the Chinese housing bust, there are stark differences. Most Chinese pay for their homes in cash and don’t borrow heavily. So they are under far less pressure to sell than their U.S. subprime counterparts who are pressured by interest and principal payments.

On the other hand, the Chinese housing bubble seems to be of a greater magnitude and not all depends on the consumer, whose debt load at the end of 2013 was only 23 percent of GDP, a big part of it mortgages.

HSBC compared the total value of residential housing to total GDP and found that China has surpassed the level Japan saw before its stock and real estate markets collapsed in 1990.

At that time, all residential real estate in Japan was worth 3.7 times its GDP. Hong Kong at 3 in 1997 and the United States at 1.7 in 2006 pale in comparison.

Numbers by the Survey and Research Center for China Household Finance stretch the imagination: More than one in five homes in China’s urban areas is vacant, with 49 million sold but vacant units, and 3.5 million homes that remain unsold.

The other problem is that most of the debt incurred building this huge bubble is on the books of property developers.

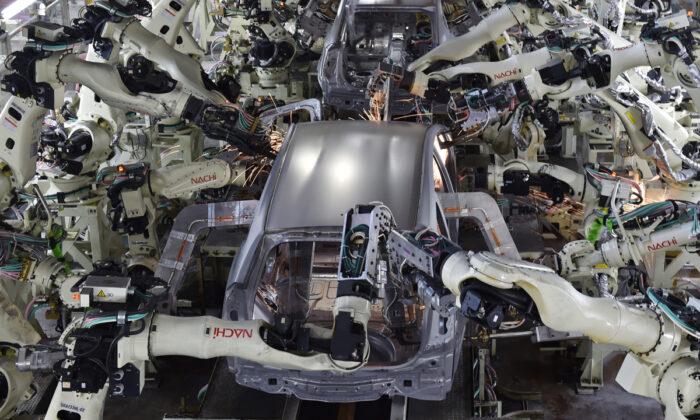

“Quite simply, China has produced and built far too much capacity, through overinvestment in steel and cement firms and in accelerated housing development. In the process, it has amassed the largest buildup of bad debt in history,” writes economist Richard Vague.

Private debt now stands at 211 percent of GDP, according to Vague, similar to levels seen in Japan before the crash and a big part of that is debt backed by real estate.

“China today is likely to have an estimated $1.75 trillion to $3.5 trillion in problem loans—a figure well in excess of the $1.5 trillion of total capital in China’s banking system,” wrote Vague.

Evergrande First to Go

Similar to U.S. subprime in 2008 (Countrywide Financial), we are starting to see cracks, also on the corporate level.

On March 17, Evergrande Real Estate Group, one of the country’s largest developers announced it had secured new financing (i.e. a bailout) from large state-owned banks. How much? A staggering $16 billion.

This makes the $4.1 billion Bank of America spent on Countrywide Financial at the beginning of 2008 pale in comparison. It can only be hoped that losses don’t multiply the same way they did at Countrywide, but chances are they will.

According to company filings as of June 2014, it only had equity of $15.74 billion. So without the $16 billion bailout, the company would have gone bankrupt.

Rumor on the street has it Evergrande could not repay the debt it owed to one of its major construction contractors, which subsequently stopped all activity. Before the bailout, analysts were speculating the company would have to sell all of its assets at a 55 percent discount to stay afloat.

This story is hardly surprising, given that trade and other payables made up $18.5 billion of all of Evergrande’s liabilities ($38.5 billion), around half of the total in percentage terms.

As with Countrywide and Bank of America, Chinese banks did well to plug the hole in the sinking ship because Chinese developers and construction companies are interwoven in an obscure chain of Ponzi credit. If one doesn’t pay, the other will almost certainly default.

At the end of this chain stands the Chinese banking system and by extension the Chinese regime. Both are too big to fail and too big to bail out at the same time.