Commentary

This week the U.S. Department of Justice announced indictments against

nine Chinese nationals for acting as illegal agents in the United States, roaming the country to intimidate and harass Chinese nationals living in the United States—including dissidents—with one clear aim: to force them to return to China “voluntarily.” One of the nine is even a Chinese prosecutor.

Unfortunately, nothing about this is shocking. In fact, already late last year, eight other Chinese nationals were accused of conducting “an aggressive harassment campaign on behalf of China to pressure political dissidents and fugitives in the United States to return home to face trial,” according to The New York Times.

These campaigns where agents are sent abroad to hunt Chinese nationals—often those critical of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—take different forms by which, according to the scattered official statistics available, at least thousands of people have thus been forced to return. A forthcoming report by Safeguard Defenders delves deeply into these different techniques and numbers, providing a first comprehensive overview of the CCP’s extra-judicial operations abroad.

Meanwhile across the pond, in Europe and its neighborhood, just in the last week alone Safeguard Defenders has witnessed a number of dramatic cases. At this very moment, as announced on July 25,

one Uyghur activist is detained in Morocco, facing deportation to China. While Yidiresi Aishan traveled to Morocco legally as a Turkish permanent resident, he was detained upon arrival at Casablanca Airport, as an Interpol Red Notice, of which he was unaware, had been issued by China. Yet another, Xu Zheng, was hiding from the Chinese police after having criticized the People’s Liberation Army (PLA or Chinese military) on Twitter in Ukraine. Xu was quickly identified and threatened to be returned via extradition if he did not oblige to the police’s orders. He managed to escape to the Netherlands just last week, and has just obtained asylum. His situation may sound familiar, as very recently I wrote about

teenage dissident Wang Jingyu. Wang, also living in Turkey, was detained in transit to the United States in Dubai, and to be deported to China. Dubai authorities, when pressed by international media, gave an evolving set of excuses for his detention. Like Xu, Wang is now seeking asylum in the Netherlands.

Still this week, a Hong Kong resident and his family applied for asylum in Sweden. They are the first Hongkongers seeking political asylum there, in what will be a test of Swedish commitment to human rights protections and which could set a positive or negative precedent. Only a few weeks have passed since

Sweden stopped the deportation of an Inner Mongolian man back to China.

I myself returned from Cyprus just days ago, preparing for the country’s very first extradition case to China of a Falun Gong adherent. What many of these cases have in common is that the victims have been sought out for “voluntary” return first, and when such attempts failed, other means are being employed.

Those “other means” take many forms, and new forms seem to appear step by step. As noted above, the use of roaming agents is one experienced by the United States; while across Europe and worldwide, people are often pressured via their families back home. Denying people the right to renew their passports abroad is another common tactic. On top of that—often with full knowledge of their Western counterparts—China seeks to retrieve people via “disguised extraditions,” getting a cooperating state to send the person back on the basis of immigration law, even though they should seek extradition and therefore afford proper due process. As has been noted in Hong Kong, and in multiple cases in Thailand, China’s public security bureau (Chinese police) and Ministry of State Security (MSS) are not above

direct kidnappings either.

While China expands these operations—as data presented by Safeguard Defenders in its forthcoming report will show—it is becoming ever more pressing that Western nations institute fast-track options for human rights defenders to seek asylum (

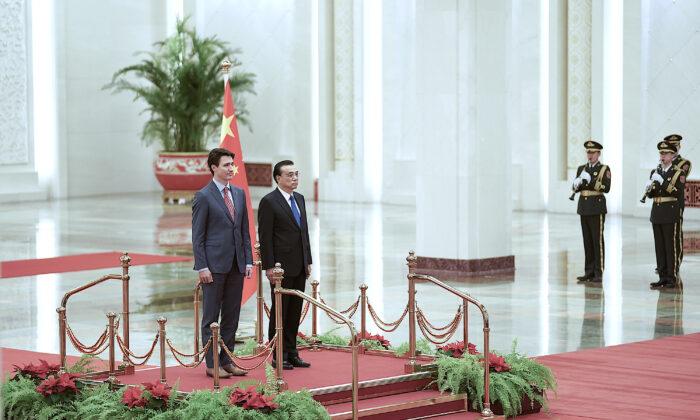

similar to what Canada announced this month), suspend and review existing extradition agreements, and pay closer attention to how China uses deportations to get its victims back.

Nowhere is that more important than across Europe and the European Union, which remains an almost free zone for China to operate unhindered, while Europe receives more and more Chinese dissidents seeking a safe haven for exile.

Peter Dahlin is the founder of the NGO Safeguard Defenders and the co-founder of the Beijing-based Chinese NGO China Action (2007–2016). He is the author of “Trial By Media,” and contributor to The People’s Republic of the Disappeared. He lived in Beijing from 2007, until detained and placed in a secret jail in 2016, subsequently deported and banned. Prior to living in China, he worked for the Swedish government with gender equality issues, and now lives in Madrid, Spain.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.