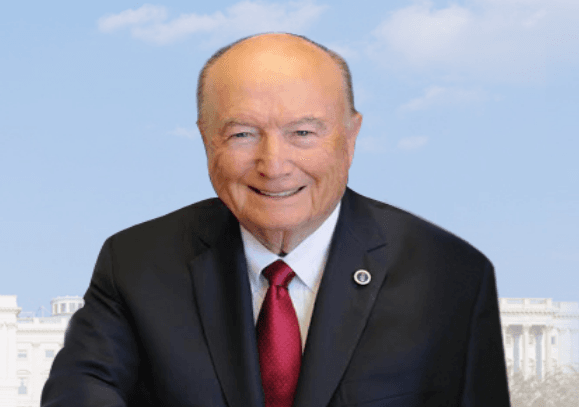

Greg Conlon, the Republican candidate for California state treasurer, is pushing for changes to the public employee pension system in order to try to save California’s credit rating.

“We [California] have the fourth-worst credit rating in the United States, while we are the wealthiest state in the Union,“ Conlon told The Epoch Times. ”It is really a disgrace to be the fourth from the last. Only Kentucky, Illinois, and New Jersey have worse ratings than we do.”