The promise to legislate for religious freedom protections was considered a key commitment of the Coalition during the 2019 election campaign.

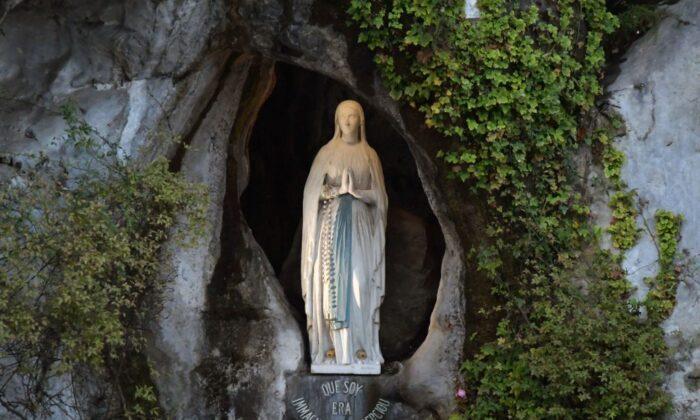

The case of the Catholic Archbishop of Hobart, Julian Porteous, who was brought to the Tasmanian anti-discrimination commission simply because he authorised the distribution of a booklet outlining the Church’s position on traditional marriage, made it clear some action to protect people of faith in this country was needed. However, while the promise to protect religious freedom was probably made with the best of intentions, it was always doomed to fail.

As Begg stated:

“Requiring secular courts to make assessments about religious beliefs represents a reversal of the separation of church and state, and this would confer on the courts the inappropriate role of defining religion and determining which religious practices or beliefs are legitimate. This is an inevitable consequence of the secular law intruding into the religious sphere.

“This is a dangerous threshold to cross. Once the courts are involved in making decisions about the legitimacy of religious beliefs, there is no limit to how far the secular state can mandate religious affairs.”

The fundamental problem is that the legislation was seen through the prism of discrimination, rather than that of fundamental freedom. Broadly speaking, under the Bill, religious organisations would have been “exempted” from anti-discrimination laws.

In Stead’s view, the Morrison government should have moved the debate away from discrimination.

Any reform should not use the language of discrimination, but actually put Australia in line with its international human rights obligations to protect religious freedom, most notably in article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Moreover, the government should protect not only religious freedom but freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, freedom of association and the right to peaceful assembly, which rights are also enshrined in the ICCPR.

There is a reason for this. These are all fundamental freedoms and are therefore intertwined. Indeed, in Evans v State of New South Wales (2008), the Full Court of the Federal Court declared that “religious beliefs and doctrines frequently attract public debate and sometimes have political consequences reflected in government laws and policies.”

In accordance with the more tolerant and inclusive values of our democratic society, the discussion should not be prohibited. On the contrary, a healthy liberal democracy depends on the good faith of its members to tolerate speech they may find disagreeable—and to disagree in open debate.

Australia is a society where people of different faiths and of no faith have to relate to one another and develop ways of living together. That being so, everyone should avoid being “uncomfortable” in robust conversations about religion.

Indeed, the idea that any group should be sheltered from criticism is totally inimical to freedom of speech, which is a cardinal precept of every free and democratic society and an indispensable shelter against totalitarianism.

Indeed, freedom of speech was described in 1966 by Enid Campbell and Harry Whitmore as “the freedom par excellence; for without it, no other freedom could survive.”

Prime Minister Scott Morrison should be reminded that it is simply impossible to protect any group’s right to not be offended without grievously infringing on the rights of others who strongly disagree.

Unfortunately, however, there have been several statements from the prime minister which done little to contribute to preserving the sanctity of freedom of speech.

According to Morrison, “Free speech doesn’t create one job, doesn’t open one business, doesn’t give anyone one extra hour. It doesn’t make housing more affordable or energy more affordable.”

And therein lies the problem.

It’s actually difficult to carry through with something if you don’t prioritise it, which explains why the government went the wrong way about trying to protect religious freedom, and why the Bill was doomed from the start.