Australia’s domestic spy agency will no longer use terms such as ‘left-wing,’ ‘right-wing,’ and ‘Islamic extremism’ when describing potential terrorist or security threats to the nation.

Mike Burgess, director-general of the Australian Intelligence Security Organisation (ASIO) said the left-right and Islamic labels were “no longer fit for purpose”, and the agency would, instead, use the categories “religiously motivated violent extremism” and “ideologically motivated violent extremism.”

“We are seeing a growing number of individuals and groups that don’t fit on the left-right spectrum at all; instead, they’re motivated by a fear of societal collapse or a specific social or economic grievance or conspiracy.

“More often than not, they are young, well-educated, articulate, and middle class—and not easily identified,” he said. “The average age of these investigative subjects is 25, and I’m particularly concerned by the number of 15 and 16-year-olds who are being radicalised. They are overwhelmingly male.”

Burgess also said extremists were reacting to COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, and the U.S. presidential election.

Investigations surrounding “ideological extremism” had grown from around one-third of the agency’s caseload to 40 percent, reflecting global trends.

“In November, police charged [an] individual with planning to undertake a terrorist attack in the Bundaberg region,” Burgess said. “And in February of this year, in New South Wales, an individual was arrested and charged with two counts of acts done in preparation for, or planning, a terrorist attack.”

The spy chief also said the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic had accelerated the evolution of domestic threats and that the spy agency was working to stay ahead of the game.

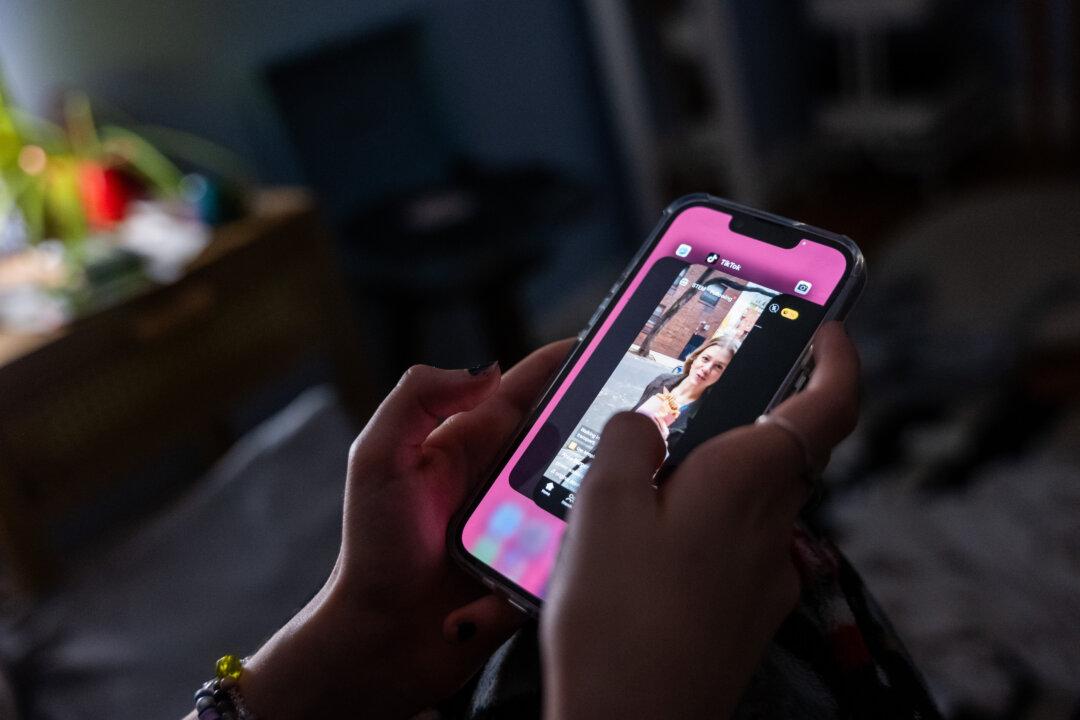

“For those intent on violence, more time at home online meant more time in the echo chamber of the internet on the pathway to radicalisation. They were able to access hate-filled manifestos and attack instructions, without some of the usual circuit breakers that contact with community provides,” he said.

Burgess warned that extreme right-wing propagandists were using COVID-19 to portray the government as an oppressor, and claiming globalisation, multiculturalism, and democracy were failing.

While Islamic extremists were portraying the pandemic as “divine retribution” against the West for alleged persecution against Muslims.

For foreign spy networks, the lack of international travel meant the tradecraft of spying simply evolved and moved online.

“Rather than a spy sidling up to a target in a train station, he or she is now more likely to send a friend request, or a job offer. Or a spy might spam out hundreds of messages, and then sit back to see who responds,” Burgess said.

In the last three years, however, the agency has also been disrupting traditional espionage activities, including “infiltration, coercion, or the recruitment of sources” across the country, sometimes targeting governments in each state and territory.

“Foreign spies are constantly seeking to penetrate government, defence, academia and business to steal classified information, military capabilities, policy plans and sensitive research,” Burgess said.

“Some of the spy clichés—like dead letter drops and writing in code—are real and are used by foreign spies and agents. Last year, an ASIO surveillance team spent a day following a spy around one of our capital cities as the spy scouted for dead letter drop sites.”

ASIO also identified a “nest of spies” working for a foreign intelligence service.

The spies had targeted current and former politicians, a foreign embassy, and state police service.

They even successfully recruited an Australian government security clearance holder who had access to sensitive defence technology.

ASIO intercepted the individual and cancelled their security clearance.

“We confronted the foreign spies, and quietly and professionally removed them from Australia,” Burgess said.

“Prosecutions are only one weapon,” he added. “Our advice helped Home Affairs deny and cancel a number of visas. And often, merely questioning a spy or their proxy is enough to make them pack up and flee the country because they know their cover is blown.”

“And before you jump to conclusions—and to underline my point that multiple countries are trying to conduct espionage and foreign interference in Australia—I want to point out that the foreign intelligence service was not from a country in our region,” he said.

“And no, I’m not going to name the country. That would be an unnecessary distraction.”