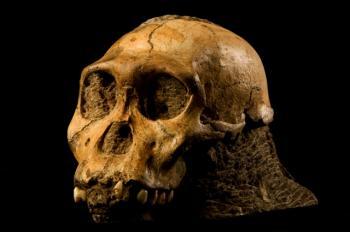

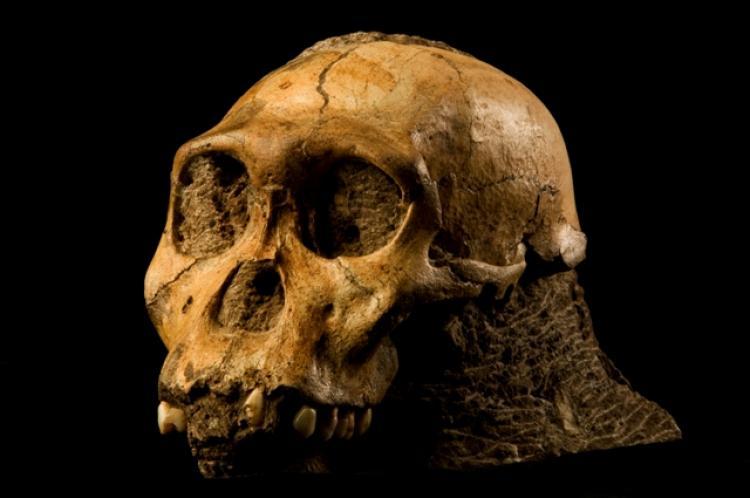

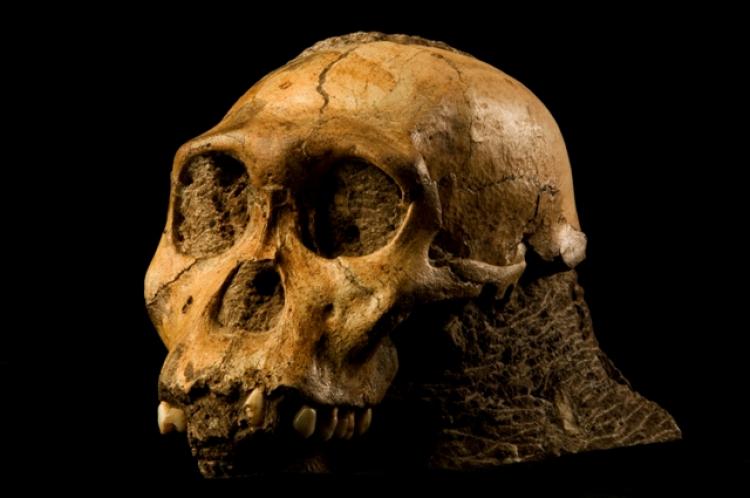

Two hominid skeletons that date back to about 1.9 million years ago were recently discovered in Africa. The fossils, of a nine-year-old male and an adult female, are said to be of a new hominid species named Australopithecus sediba. They have long legs and can stand and stride like modern humans. Scientists think they can probably run, too.

“It is estimated that they were both about 1.27 metres, although the child would certainly have grown taller. The female probably weighed about 33 kilograms and the child about 27 kilograms at the time of his death,” said Dr. Lee Berger of Wits University.

The skull and fragments of the child—about 40 percent of his entire body—were transported to the ESRF in Grenoble, France, where a nondestructive tool known as X-ray synchrotron microtomography was used to examine them.

Although found under avalanche deposits, the fossil was very well preserved, to the extent that you can count the teeth in the skull. Its remarkable preservation encouraged scientists to fully examine it, according to a press release from European Synchrotron Radiation Facility.

Paleoanthropologist Dr. Paul Tafforeau, who developed the instrument, originally started to use it to study fossil primate teeth and develop synchrotron imaging for paleontology. The technology enables scientists to visualize the inside of a fossil block, sometimes even up to micron scale without breaking the fossil.

Two papers about this find were published on April 9 in Science.

“It is estimated that they were both about 1.27 metres, although the child would certainly have grown taller. The female probably weighed about 33 kilograms and the child about 27 kilograms at the time of his death,” said Dr. Lee Berger of Wits University.

The skull and fragments of the child—about 40 percent of his entire body—were transported to the ESRF in Grenoble, France, where a nondestructive tool known as X-ray synchrotron microtomography was used to examine them.

Although found under avalanche deposits, the fossil was very well preserved, to the extent that you can count the teeth in the skull. Its remarkable preservation encouraged scientists to fully examine it, according to a press release from European Synchrotron Radiation Facility.

Paleoanthropologist Dr. Paul Tafforeau, who developed the instrument, originally started to use it to study fossil primate teeth and develop synchrotron imaging for paleontology. The technology enables scientists to visualize the inside of a fossil block, sometimes even up to micron scale without breaking the fossil.

Two papers about this find were published on April 9 in Science.