Commentary

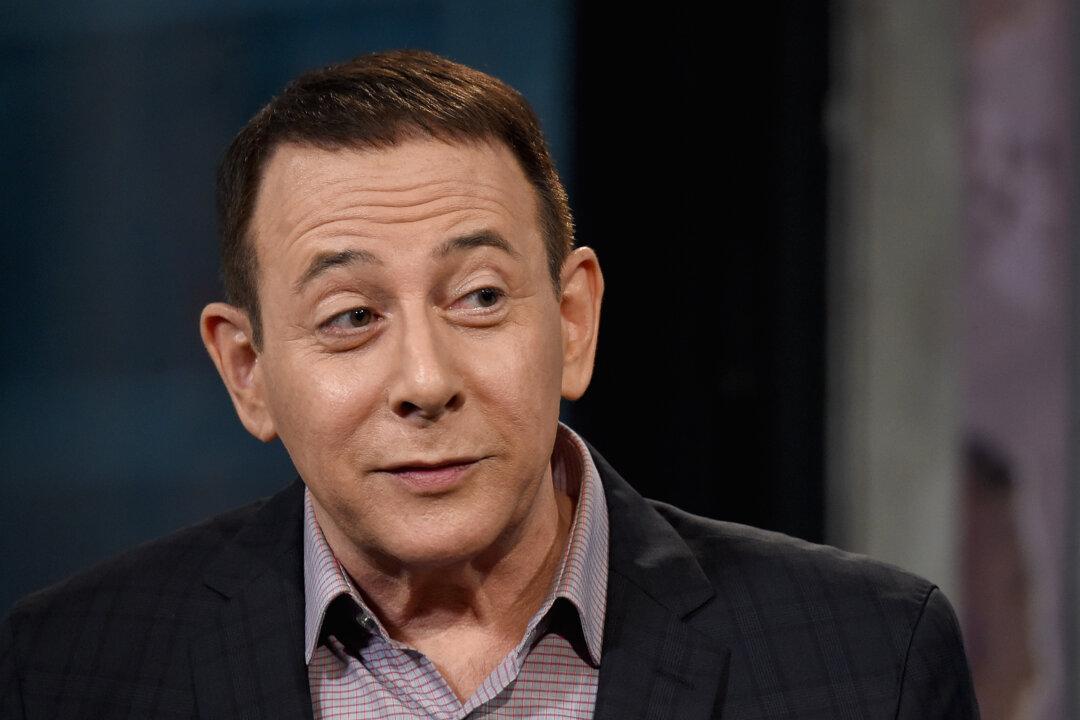

Paul Reubens, the legendary creator of Pee-wee Herman, has died at the age of 70. And this sad day gave me a chance to reflect on reasons to love the movie “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure” (1985) so much. It isn’t obvious what’s profound and meaningful about the movie. Yes, while it’s incredibly imaginative, hilarious, and oddly magical, it surely isn’t morally or philosophically sophisticated.