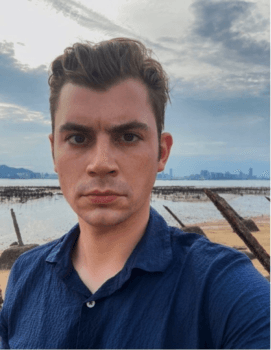

I’m on the front lines.

Alone on a fortified island beach, steel-spiked anti-invasion barriers around me.

An American face-to-face, facing off against totalitarian China.

It’s been 10 months since I stood on the steps of the U.S. Capitol building, meeting with my House representative, a decorated war veteran, asking if the result-changing presidential election fraud—a well-documented disenfranchisement of American voters facilitated by the cover of China’s coronavirus—would be corrected in Congress the next day.

It’s been 10 years since I was last here on Taiwan-governed Quemoy (also known as Kinmen), the previous time having ferried over from the Chinese city of Xiamen, its skyline now looming across the water only a few kilometers away.

How did I get here?

The story I want to tell is a journey of geography, knowledge, and spirit, as well as a perspective on global geopolitical developments over the past decades.

It’s a story of how I’m discovering my destiny, fighting for the future of the United States, and working to defend freedom, democracy, and human rights around the world.

‘The World Is Flat’

As a college freshman in 2005, after graduating from a Catholic high school one mile south of Gary, Indiana, I attended a student conference titled “Entrepreneurship in a Globalized World.” At the conference, which focused on “socially responsible business for a flat world,” it was strongly recommended that attendees read “The World Is Flat,” a then newly-published book by New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman.I did so, and through this book learned that China was essentially projected to be the future of the global economy. As a business major with a passion for language, I decided, despite being enamored of the French language and having no real prior interest in Chinese culture, that learning Mandarin would be a smart and practical course of action.

I dived in and registered in college Mandarin courses the next fall, before completing an internship during the summer of 2007 in Beijing at a Chinese real estate listing website, SouFun.com, three years before it went public on the New York Stock Exchange. The internship took place a year before the 2008 Beijing Olympics, and there was a buzz of excitement in the country’s capital. China was the place to be, with reported gross domestic product (GDP) growth of more than 11 percent that year, and people from around the world wanted a piece of the action.

I went on SouFun-hosted tours of seemingly endless new real estate developments, honed my Chinese-language bargaining skills at Beijing markets, picked up the game of squash at the Kempinski Hotel, where my mother’s cousin—a successful energy entrepreneur and engineer —was staying as a newly appointed Beijing-based executive at an American company, and traveled with him on a field trip to an energy production site in China’s coal-rich Shanxi province.

Ever the charismatic and encouraging mentor, my second cousin, whom I call an uncle, told me that I was joining the trip in the capacity of his Chinese-language interpreter. As a 20-year-old with a year of entry-level university Mandarin courses in the United States and a couple months’ worth of fierce market haggling in Beijing under my belt, I took this seriously and brought along my paperback English-Chinese dictionary, just in case I would need some vocabulary that I hadn’t yet acquired in class. We visited the production site during the day, where drills were boring into the ground and farmers in the surrounding fields were loading cabbage, which they would later sell for a few yuan per kilogram, onto motorized tricycles.

Later, following a dinner with a local Communist Party official and his entourage, I ended up in an empty village nightclub, on a dance floor with flashing disco lights and smoke machines, attempting to sing “Auld Lang Syne” as the smiling official, his face red from baijiu —Chinese firewater—nodded along and applauded with as much enthusiasm as he could muster. Having already sung a few songs in Mandarin with his underlings, the official insisted, despite my initial demurral, that I also sing a song. The only Mandarin song that I had learned up to that point was a classic called “The Moon Represents My Heart,” which did not seem to be an appropriate choice for the situation. Scanning the outdated and very limited English-language options that the karaoke machine presented, I opted for the New Year celebration staple “Auld Lang Syne,” the only song that I readily recognized. Such fun and awkward adventures were commonplace for foreigners in China then, and this was just one of the many memorable experiences I had early on in the country. I was confident that my choice to learn Chinese had been the right one indeed.

The Girl with the Cello

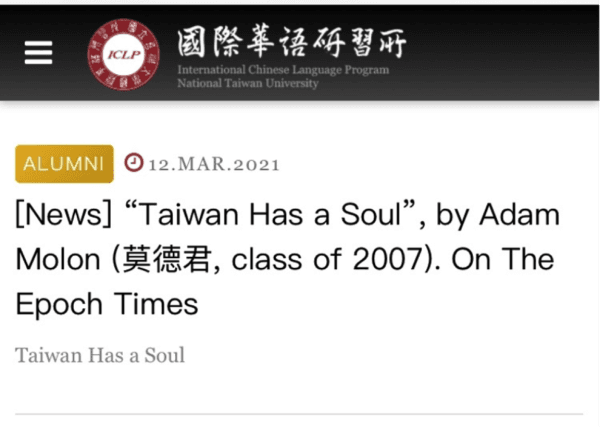

In September 2007, following my summer in Beijing, I arrived in Taiwan for an academic year of study at National Taiwan University’s International Chinese Language Program (ICLP). I did not know much about Taiwan, a democratic island nation of 23 million people, other than the Chinese Communist Party’s spurious claims on it and continuous threats to take it by force. I assumed that, since Taiwanese people also speak Mandarin, things would operate similarly to China there. I soon learned that this was in many ways an incorrect assumption, and gradually dropped my Beijing-influenced accent as I began to pick up the light and clear tones of Taiwanese Mandarin.I rented a room in the Taipei apartment of an octogenarian Taiwanese couple, and they told me to call them “ah-po” and “ah-gong,” Taiwanese words for grandmother and grandfather. Every day, when I left for class, my ah-po and ah-gong would call out, “shang ke le,” meaning “you are going to class,” and would pair this traditional acknowledgment with reminders to “duo chuan yi-dian” (wear a coat) if it was cold or “dai yu-san” (bring an umbrella) if it was raining. When I returned from class, they would call out, “hui lai le,” or “you’re back.” Through daily interactions with my Taiwanese grandparents, I learned much about the traditional values and upright nature of Taiwanese society.

Several weeks after arriving in Taipei, I met a special girl at the squash courts of National Taiwan University. Knocking on the glass wall of the court where she was playing alone, I asked if she would like to play together. A fresh graduate of National Taiwan University who was applying to graduate schools in the United States, she introduced me to Taiwanese culture, and I provided as much insight as I could into America’s.

Late on the evening of October 9, a few weeks after first meeting, we sat together on the stage of an amphitheater in Da’an Forest Park, Taipei’s version of Central Park, and shared tranquil moments that felt transcendent in their clarity. Wearing a peach-colored dress that evening, she described, as we looked out at the empty seats and night sky, how she had played the cello in a concert here years before. I only discovered several hours later that the new day, October 10, was Taiwan’s National Day, called Double-Ten Day. This was the first time that I learned of Taiwan’s National Day, and I associate it with this girl, these moments, this stage.

As we’ve stayed in touch through the years, meeting in different countries and across continents, this special girl has become a muse, for me representing the essence of Taiwan.

What would it mean if China were to invade Taiwan, taking away the freedom, democracy, and human rights of the Taiwanese people?

What about that bright and beautiful girl on stage playing the cello, who would go on to graduate from Taiwan’s best university and pursue her dreams?

Crash Landing in China

During my academic year in Taiwan, I won a language study scholarship from the U.S. State Department, and in the summer of 2008 arrived in the city of Suzhou, located in China’s coastal Jiangsu province near Shanghai, to complete the State Department’s Critical Language Scholarship (CLS) program.Sometimes called “the Venice of the East,” Suzhou was famously visited by Marco Polo in the 1200s, and has long been known for its commerce, canals, and gardens. In Chinese, there is a well-known saying, “While there is heaven above, the world below has the cities of Suzhou and Hangzhou.” A classmate put it more prosaically one day, having had a few weeks to size up the city. “I would call this ‘white bread’ China,” he said to the class before the day’s lessons began. “It’s the China you grew up seeing in National Geographic documentaries.” During the summer, our class made a trip to the cities of Kunming, Dali, and Lijiang in the southwestern province of Yunnan, which borders Tibet. While not in class, I completed an internship that I had lined up at the Suzhou Industrial Park branch of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), one of China’s “big four” state-owned commercial banks, in order to learn more about China’s economy.

It was the summer of the long-awaited Beijing Olympics, and, on Aug. 8, American classmates and our local Chinese instructors gathered around old televisions pushed into a dormitory hallway for a makeshift viewing party of the opening ceremony. Tuned in to state broadcaster China Central Television, we watched what for totalitarian China served as an announcement of its arrival on the world stage as a global power after decades of rapid economic growth, greatly accelerated by their admission to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001.

While China’s reported economic growth continued at breakneck speed in 2008, the U.S. economy was headed for an imminent crash. In September 2008, just after I had returned to the United States for the fall semester, the investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed, marking the defining moment of the global financial crisis. The crisis plunged America’s economy into the Great Recession, a downturn spanning years that was at the time considered the worst global economic crisis since the Great Depression. Having previously worked, during the summer of 2006, as a trader’s assistant on the trading floor of the Chicago Board of Trade, I had vague aspirations to become an investment banker or a securities trader. Those aspirations were checked by reality in 2008, with financial institutions across the United States laying off large portions of their staff and implementing hiring freezes.

At that time in my junior year as a finance and Chinese language double major, my prospects for landing a career-launching position in America’s financial industry looked bleak. China, however, was being hailed as the engine that would pull the global economy out of the doldrums. My choice to study Chinese appeared even more prudent.

The following summer in 2009, I completed the State Department’s Critical Language Scholarship Program for a second time, this time at Heilongjiang University in the northeastern Chinese city of Harbin, while also interning in my free time at ICBC. Harbin sits near Russia, and its architecture shows the strong Russian influence that has molded the city during its history. The city hosts a popular ice sculpture festival each winter, and even in the summer, strong winds from across the steppes provided an indication of how bitterly cold it would be there in only a few months’ time. Highlights from the summer included a visit to Confucius’ hometown, Qufu, in the Shandong province, a climb up Mount Tai, which is famed for its cultural significance and prominence in historical Chinese literature, a trek through the region of Inner Mongolia to the city of Manzhouli on the Sino-Russian border, as well as a trip to the top of volcanic Mount Paektu, which has a mythical status in Korean culture and straddles China’s border with North Korea. Looking out across Mount Paektu’s crater lake, called Heaven Lake, I took in a scenic, spruce-lined view of the Hermit Kingdom.

After returning to the United States for the fall semester of my senior year, I again departed for China, arriving at Nanjing University in January 2010, as a student in the U.S. Department of Defense’s Chinese Language Flagship Program, which is administered by the National Security Education Program (NSEP). My spring semester in Nanjing, which is the capital of the Jiangsu province and was previously China’s national capital before the Communist revolution in 1949, was my final as an undergraduate, and after finishing it I became the first student from Indiana University to complete the Chinese Language Flagship Program.

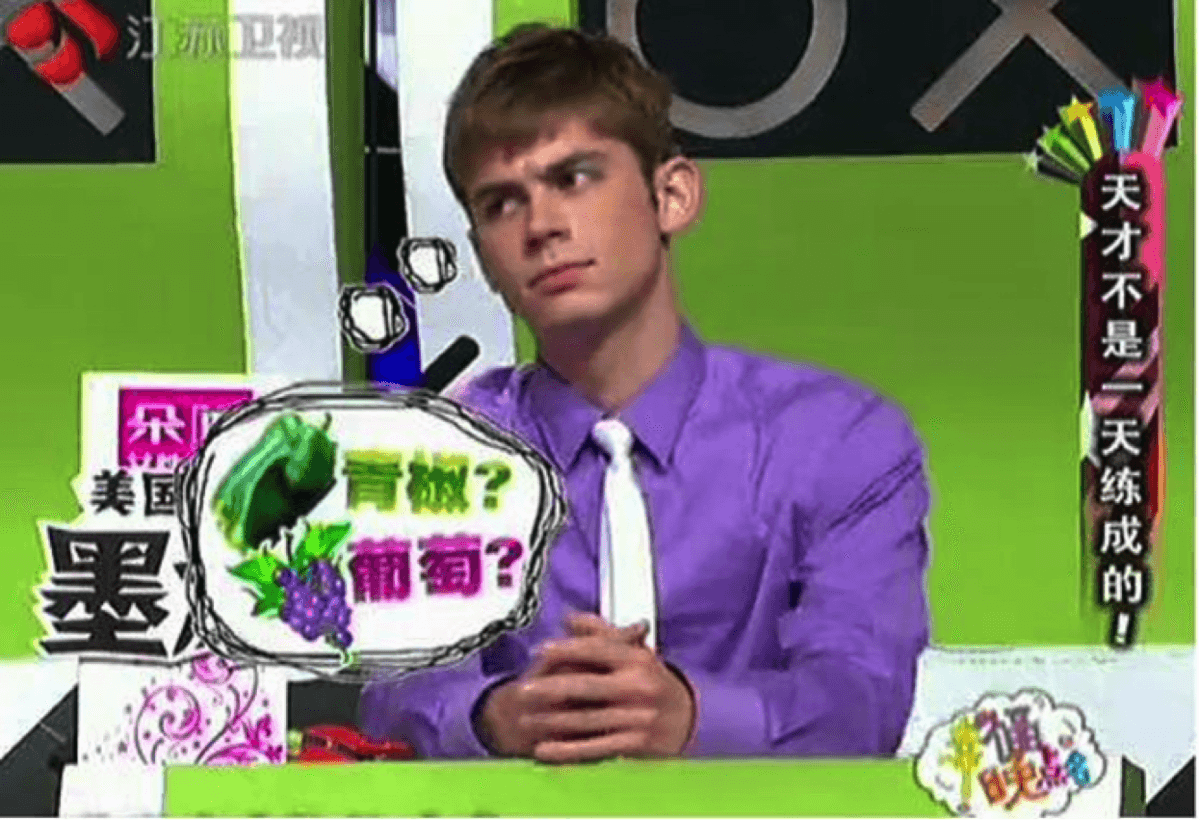

In June 2010, shortly after the language competition, I was invited to join a nationally broadcast, Chinese-language variety show called “Happy Night” on Jiangsu TV, one of China’s largest television networks. Through the show, seen by millions across China, I became known to viewers by my Chinese name “Ink Dragon,” pronounced “Mo-long” in Mandarin, an approximation of my surname.

Becoming Ink Dragon

On the late-night variety show “Happy Night,” co-hosted by former supermodel Li Ai and a quick-witted jokester named Peng Yu, I had the opportunity to joust and parry in Mandarin with an on-set panel of some of China’s most talented and entertaining young people, many of whom would continue on to increased prominence in Chinese media, including as TV hosts and movie actors. As part of a special arrangement that Jiangsu TV had made in order to improve its production capabilities and learn from Taiwanese media, the show was co-produced by the well-known Taiwanese company Golden Star Entertainment, which had produced the hit Taiwanese entertainment shows “Here Comes Kangxi” and “University.”

Jiangsu TV’s “Happy Night” featured guests like the then-up-and-coming Chinese pop singer Hu Xia, the Taiwanese star Jolin Tsai, known as the “Queen of Mandarin Pop,” and silver screen megastars Fan Bingbing and Huang Xiaoming, among others. The national television exposure that I gained from my appearances on “Happy Night” led to more media opportunities, including the chance to participate in a nationally broadcast competition on Shanghai TV. The show pitted me against four Chinese actors in a series of challenges, and the five of us were voted on each round by an in-studio audience. Partnering with a famous Taiwanese model named Makiyo as part of the show’s format, I ultimately won, and was surprised with a literal shower of champagne when the final votes came in. When I left the studio, I took an empty champagne bottle with me as a trophy by which to remember this amazing moment.

In less than four years’ time, I had gone from a Chinese 101 student in the United States to a Mandarin-speaking actor who was winning nationally televised competitions in China. It felt like the fun and excitement would only continue. But as a Chinese proverb says, “There is no such thing as a banquet that never ends.” A few months into 2011, it was announced that “Happy Night” would be canceled. Having appeared in more than 70 episodes of the show, “Happy Night” had been my mainstay in Chinese media, and my future became more uncertain.

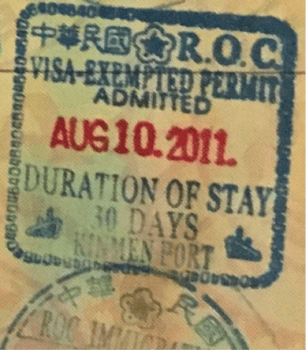

After “Happy Night” ended, I was able to pick up piecemeal media work, like a role in a short-lived regional variety show broadcast within the Jiangsu province, as well as a one-off job as a Chinese-English interpreter for one of the international guests on another Jiangsu TV program. Shortly, thereafter, I found an opportunity to source and book guests for a variety show called “Marvelous Encounters,” sponsored by Wrigley’s Doublemint Gum and broadcast nationally by Zhejiang TV from the city of Hangzhou, located a little more than an hour southeast of Nanjing by high-speed rail. In August 2011, after traveling to Hangzhou and spending a day in the “Marvelous Encounters” studio, during the filming of an episode that featured as special guests a Hong Kong pop duo called Twins, I embarked on a quest well-known to foreigners in China at that time: a visa run.

Visa runs were periodic rituals in which, to meet the requirements of a Chinese visa and stay within the law, a foreigner had to periodically leave China, have their passport stamped with a proof of exit, and then re-enter. Having to make a visa run could be one of the most nerve-wracking, exhilarating, and outright fun aspects of being a foreigner in China, sometimes all at once. It could be full of unexpected adventure that would be remembered for a lifetime.

The trip that I made at this moment in time turned out to be just such an adventure. It served as a meditative interlude in my life and has maintained a mystical quality in my memory. Finding myself at an intersection of youth, roving freedom to wander without a set itinerary, and uncertainty surrounding my future, with the endless possibilities that accompanied it, I hopped on a high-speed train bound for the semitropical city of Xiamen on China’s southeastern coast, with the destination of the Taiwan-governed island of Quemoy in my sights.

Peach Blossom Spring

Xiamen faces the heavily militarized island of Quemoy, separated by only a few miles of ocean. In the 1600s, Koxinga, one of Taiwan’s national heroes, had maintained a base on Quemoy. In more recent times, Quemoy had been regularly shelled by mainland China from the 1950s until the late 1970s. The island’s most well-known products, in addition to its famous brand of firewater, are knives made from the plentiful metal of Chinese-fired shells. It had been decades since the last shellings, and tensions had eased to a level that allowed the establishment of a regular civilian ferry service between Xiamen and Quemoy. I was able to take a ferry to Quemoy, where I would have my passport stamped before re-entering the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The slow-moving island of Quemoy, featuring quiet palm-lined streets, distinctly Taiwanese shops, and kindly locals, felt like a hidden paradise. It reminded me of the story of “The Peach Blossom Spring,” written by my favorite Chinese literary figure, Tao Yuanming, whom I had cited in the interview that I gave for The Yangtse Evening Post article featuring my Chinese-language poem, as well as in my appearance on Shanghai TV.

One of Tao Yuanming’s most celebrated works is a story called “The Peach Blossom Spring.” It tells of a fisherman who one day happens upon a grove of peach trees by a stream, then follows the stream to its source: a spring in the side of a mountain. The fisherman is able to enter the mountain through the spring’s opening, and inside the mountain he finds an idyllic world where people whose ancestors had fled the turmoil of another dynasty hundreds of years before are living in contentment and happiness. The people of the Peach Blossom Spring had lost all touch with current events since their ancestors’ withdrawal from the known world and were dismayed by the fisherman’s news of the calamities that had continued to occur outside. Before the fisherman departs, the people ask him not to mention their presence to any outsiders so that they may continue to live in peace in their own utopia. After leaving, the fisherman marks the path to the Peach Blossom Spring and tells a government official of it. Others try to retrace the route, but are unable to find the Peach Blossom Spring.

From my perspective, Quemoy and Taiwan represent an ideal, like the Peach Blossom Spring chronicled in Tao Yuanming’s story. I see Taiwan as a refuge of freedom and tranquility, tucked just outside the reach of the oppression and cruel realities of life in totalitarian China.

While living in China, I had gradually discovered that, beyond the artificial bubble of bright lights and laughter in TV studios, China has already, to a great extent, lost its traditions and culture to totalitarianism under the Communist Party. I had learned firsthand how to navigate the systematic government censorship and individual self-censorship that takes place in China—including in TV and other media—had read the forbidden histories of totalitarian China’s deadly and disastrous Great Leap Forward, Cultural Revolution, and Tiananmen Square Massacre, and had seen and felt the desperation of Chinese people to escape the PRC, a nation that I sometimes thought of as the world’s largest prison. I had found that, overall, China has sadly become a largely soulless society without trust or a sense of common good. Subjects of the PRC readily sell each other out if practical or political circumstances call for it. There seem to be no higher beliefs or value systems beyond money and political power, which might provide a taste of the stability and security in life for which most in China are starving. Taiwan, by contrast, has maintained its culture, values, and traditions. Without a totalitarian government to brainwash, control, and oppress them, its citizens live in freedom, treat each other with dignity and respect, and nourish their souls and their humanity with beliefs in higher powers and causes.

In short, Taiwan is the country that China wishes it could be but can never become under its totalitarian system. Jealous and threatened by Taiwan’s existence and example, the Chinese Communist Party and their subjects in the PRC, nearly all of whom have been brainwashed by the Communist Party since elementary school, say that they are determined to take over Taiwan, by force if necessary, and integrate it into China. Their thought process, it seems, is that if Chinese have to live in misery and without freedom, the Taiwanese should have to also.

“The Taiwanese think they’re so special, but they’re no better than us,” is a resentful sentiment that I have heard expressed in numerous conversations with Chinese people from all walks of life. It’s a classic case of “misery loves company.”

Through all of this, the Taiwanese, like the hidden villagers that the fisherman encountered in Tao Yuanming’s Peach Blossom Spring, simply want to continue to live their lives in peace and harmony, despite the external threats and calamities swirling around them. I feel peace and harmony in Taiwan, and I’m thankful it exists. I want it to stay free for the sake of the Taiwanese people and the world.

Seeing all that I had before my first visit to Quemoy, I viewed China as a mostly lost cause. At the time, it had already been more than sixty years since the Communist Party took over. The Chinese people had been subjugated and, at that point, after sixty years, weren’t they complicit in upholding the Chinese Communist Party’s power and totalitarian system?

Nanjing to New York

In September 2011, shortly after returning to Nanjing from Quemoy, I learned that an anchor was needed for an English-language news program called “Hello, Jiangsu,” broadcast within the Jiangsu province and internationally. Following an interview and audition, I secured the job and, with it, a rare inside view of hard news production in Chinese state-controlled media.

Shortly after starting with the show, I began an application to Columbia University’s School of Journalism on the basis that I possessed fundamental credentials as a newly minted TV anchor. When auditioning for “Hello, Jiangsu,” I could see that the anchor role had the potential to serve as a seamless bridge back to the United States.

For one of the essays required for my application to Columbia, I wrote, “While my work at [Jiangsu TV] affords me invaluable experience from technical and cultural perspectives, I am acutely aware of the restraints and controls to which Chinese media organizations are subject. By earning an M.S. at the Graduate School of Journalism, I hope to receive formal training in American journalistic standards, and transition to an American media organization… With the substantial resources of a large media conglomerate at my disposal, I will be able to use the next months to develop my technical skills on camera and in the voiceover and editing rooms, before returning home to the United States for training in journalistic standards and access to the freedoms of speech and press that I once took for granted.”

My application was successful and, in 2012, after receiving my admissions decision, I departed Nanjing for New York City. Following graduation, I landed a role as a journalist at CNBC headquarters. At CNBC, I coordinated with editors to report and write articles that were frequently ranked among CNBC.com’s daily most-read. Later, I transitioned into the private equity investment industry, working to make investments and raise new capital at firms with billions of dollars in assets under management.

Pandemic, Fraud, Protest, Censorship

Unexpectedly, the COVID-19 pandemic spread by totalitarian China and the massive fraud that this enabled in the 2020 presidential election necessitated that I exercise my civic responsibility as an American to stand up for the integrity of our electoral system and the franchise of American voters. For the first time in my life, I exercised my right to publicly protest on Jan. 6 in Washington, DC, and was subsequently censored for the first time in the United States, something that I never imagined would happen in a nation that cherishes freedom, including freedom of speech and press.Like other Americans, I was heartened to see Donald Trump lead the United States onto a renewed trajectory of national ascent by speaking and acting on truth, common sense, and noble principle in a way that no president during my lifetime, with the possible exception of President Reagan, ever has. A crucial reason why President Trump has been able to effectively push for policies that benefit American citizens and workers, rather than special interest groups and the political establishment in both major political parties, is that he is an independently successful entrepreneur who has largely self-financed his campaigns. He is therefore not beholden to donors or the political establishment and, to their great chagrin, isn’t answerable to their interested guidance as typical politicians unfortunately have been.

Despite relentless and unjustified opposition to President Trump from many in the political establishment, corporate media, and Big Tech who feel threatened by the loss of cozy, and too often corruption-tainted, power that he represents for them, President Trump has worked tirelessly to rehabilitate our domestic industrial base, stop the shipment of American jobs abroad, and stand up against abuses perpetrated upon the United States by geopolitical rivals and ideological adversaries, particularly totalitarian China.

During President Trump’s first term, unemployment levels in the United States fell to 50-year lows, stock markets reached all-time highs, and the economy was firing on all cylinders. All the while, President Trump helped further awaken Americans and the rest of the world to the fact that totalitarian China continues to pose the greatest external threat to the United States and to global freedom, democracy, and human rights. With President Trump’s leadership, the United States was on a path that would allow the next generation of young Americans to rightly view the free and democratic United States, rather than totalitarian China, as the land of opportunity and the future of the global economy.

Then, in 2019, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) covered up the emergence of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, and spread its coronavirus around the world, creating a global pandemic and throwing nations around the world, their citizens, and their economies into sustained states of shock by early 2020. At the same time, hyperbolic health concerns surrounding COVID-19 provided the perfect cover and pretext for the unconstitutional and short-notice expansion of mail-in voting procedures that were designed to be abused in the 2020 presidential election.

In response to the election fraud that occurred, President Trump called for a protest to take place in Washington, D.C. on Jan. 6, 2021, just two weeks before what rightly should have been the beginning of his second term as president. Closely following what had happened, I knew that I should be present in Washington, D.C. to stand with my fellow Americans for the franchise of American voters and the integrity of our electoral system in the face of what was then still an attempted, rather than a realized, heist of the presidency by way of election fraud.

On Jan. 5, I met with Jim Baird, my U.S. House Representative, on the steps of the U.S. Capitol building. I had arranged the meeting in advance, explaining to Representative Baird’s office that I would be in Washington to protest. Representative Baird, a Vietnam veteran who has earned two Purple Hearts, a Bronze Star with valor, and a Ph.D., was among those in Congress who demonstrated strength and integrity the next day, objecting to the certification of Electoral College slates from certain states that enacted new election rules without consent from their state legislatures.

On the Front Lines

Having been further awakened to the malign influence of totalitarian China following its COVID-19 attack on the United States—and in the wake of the damage this has done to the US economy and the integrity of the 2020 election—I’ve used the knowledge and skills I’ve developed to continue to write and stand up for the United States, freedom, democracy, and human rights.Restoring election integrity, strengthening the security of our borders, and defending against totalitarian China’s intensifying aggression are goals that we must all work toward together as Americans. And comprehensively maintaining and increasing pressure on totalitarian China in the face of its aggression is a policy with strong bipartisan support that can serve as an important foundation for increasing unity among Americans and securing the future of the United States.

While political polarization in the United States has been evident, something that Americans should be able to agree on is that, for the sake of our country, we want the current administration to act on common sense and work for the interests of American citizens rather than special interests.

Long-running and well-documented corruption and incompetence in the track records of key administration figures, however, necessitates that, though we wish to be pleasantly surprised with integrity and competence in the current administration, Americans must civically engage, make our voices heard, and work to strengthen our nation and the integrity of our institutions with more dedication than before.

As an American, I have taken what I wrote in “Taiwan Has a Soul” literally, and am standing side-by-side with our friends, the Taiwanese people, in Taiwan. Earlier this year, I returned to Taiwan, became a member of the Taiwan Foreign Correspondents’ Club, and as a journalist have so far interviewed top government officials, prominent scholars, and accomplished authors from the United States, Taiwan, and other nations who are standing up for freedom, democracy, and human rights. In September, I won a language study scholarship from the U.S. Department of State for a third time and, while continuing to publish articles, am also honing my Mandarin language skills through this scholarship at Taiwan’s National Cheng Kung University.

While the Peach Blossom Spring in Tao Yuanming’s story was not found again after the fisherman’s visit, I’ve found my way back to the peach blossom spring of Quemoy via a different route. Instead of taking a train from Hangzhou and a ferry from Xiamen in search of a respite from totalitarian China, this time I took a train from Taipei and a plane from Tainan to stand on the front lines of democracy in defense of the free world in which I live.

Though I am a foreigner here, the people of Quemoy have been more hospitable and welcoming than I could have hoped. After wandering the islands of Quemoy and Lieyu for a few days, I spoke with a Quemoy native and author who explained the island’s history and current events in detail, gave me a tour of important cultural and historical sites, and introduced me to other residents, thus giving me the opportunity to interview some of Quemoy’s most prominent officials, politicians, and scholars.

After meeting fellow journalists on Quemoy, a Chinese-language TV news report about my journey was broadcast on the New Tang Dynasty channel, an affiliate of The Epoch Times. In the report, I noted that, because it is on the front lines, across from totalitarian China, Taiwan is protecting the freedom, democracy, and human rights of the Taiwanese people and the entire world. I stated in Mandarin, “If the nation of Taiwan still exists, the whole world still has hope.”

Americans share fundamental common values with the Taiwanese people, and by continuing to support Taiwan’s sovereignty, we can help to ensure that the United States is ultimately victorious in the calculated and deadly war that the Chinese Communist Party has continuously waged against our nation and the bright beacon of liberty for which we stand. We, together with our allies around the world, can and must defeat the Chinese Communist Party and the creeping evil it propagates.

A decade after first visiting Quemoy, I now find myself at another crossroads in life. The future is uncertain, but the experience, knowledge, and wisdom I’ve gained give me confidence in my strength to shape it. I’m thankful for the beauty and meaning I’ve found, and look to what lies ahead with hope and determination.

I’m fighting for country, for freedom, and for those I care about.

And I know that here, on the front lines, is where I should be.