Commentary

During the snowstorm, I was congested, tired, and finally forced into something I rarely allow myself—real rest. I ended up binge-watching 1883, a series I had first watched after the birth of my fourth child. Re-watching it now, years later, I saw it differently.

There are many parallels between that story and our lives today, but one theme stood out above all: the more civilized we become, the weaker we become. The closer we are to the land, the more “savage” life is—and the stronger we must be to survive it.

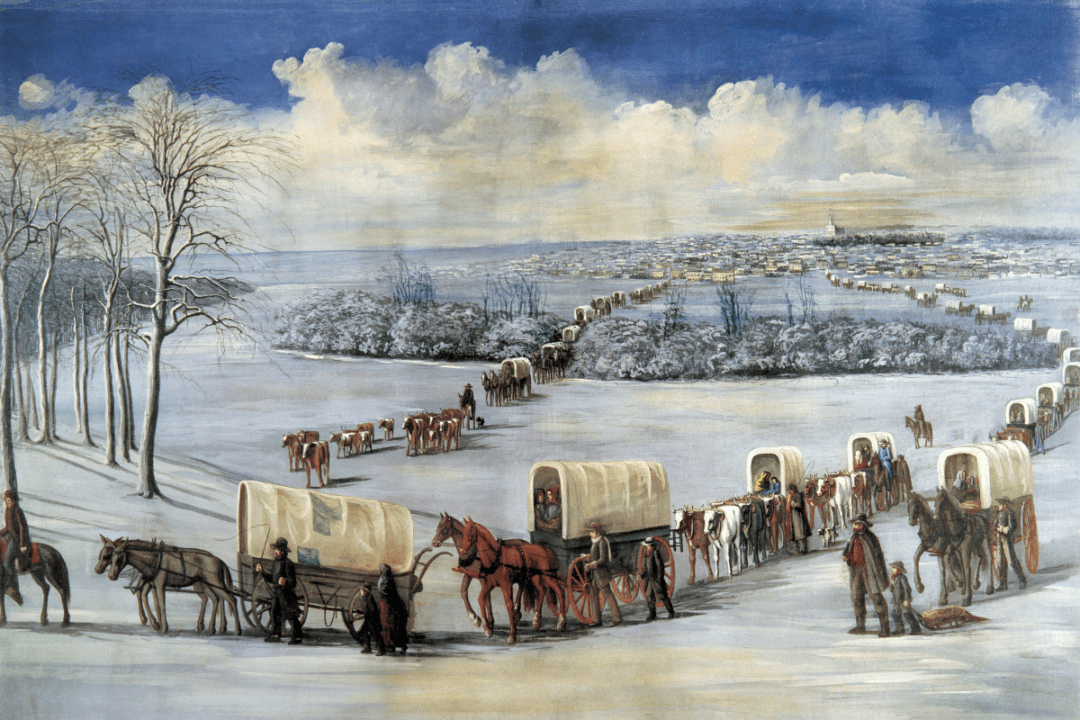

1883 follows a caravan of immigrants and dreamers trying to make it to Oregon. The perils are endless. People die again and again—horse accidents, gunfights, rattlesnakes, infected water, brutal weather, starvation, and violence. Every decision has weight. There is no buffering system. Mistakes bring swift and often fatal consequences. Survival demands constant awareness.

At the beginning of Episode 5, the narrator reflects on how cities have softened people—how civilization removes immediate consequences and creates the illusion of safety.

If that was true in 1883, it is even more true today.

We are not just softened by cities now. We are softened by systems, conveniences, and layers of protection between ourselves and reality. In many ways this is good. No one truly wants to live in a world where death is around every corner. Modern medicine, sanitation, infrastructure, and safety regulations have saved countless lives.

But there is another side to that coin.

We have strayed so far from living with the natural consequences of our actions that we now exist inside a padded version of reality. A world where bad decisions rarely carry immediate cost. A world designed to keep us comfortable at almost any price.

So where is the middle ground?

Where is the place where we can stay rooted in reality and connected to the consequences of our choices—without living in a world where going to the bathroom might mean getting bitten by a snake?

Are we even capable of finding that balance? Or has comfort become our north star?

In universities and institutions today, we see the rise of “trigger warnings” and “safe spaces,” built around the idea that discomfort itself is a form of harm. Yet discomfort is not an error in the human experience. It is part of being alive. It is part of growth. It is part of resilience.

Human beings are designed to withstand discomfort. And when we remove physical challenges from our lives, we don’t eliminate struggle—we relocate it into the mind.

We begin to manufacture problems. We magnify minor stressors. We search for identity through suffering because our biology expects resistance to push against. Without real adversity, our minds invent it.

I suspect much of modern despair is rooted in this mismatch. We evolved for survival, for movement, for uncertainty, for sunlight and cold mornings and meaningful labor. Now we live in temperature-controlled boxes, staring at blue-lit screens, insulated from both danger and purpose.

There are studies showing that blue light at night disrupts our biology, while sunrise light and firelight support mitochondrial function and overall health. Our bodies still respond to the rhythms of nature even if our lifestyles no longer do.

The pioneers navigating rivers, disease, and violence didn’t have time to wonder if they were born in the wrong body. Survival left little room for existential spirals. Their hardship was brutal, but it was real. Their minds were occupied with survival, contribution, and community.

I think about my own life. The level of restriction and pressure I felt in California was enough to make me move my family across the country. But we did not load into a wagon for a yearlong journey. We got in an RV and drove for two days. The unknown was still scary. The risks were real. But they were nothing compared to families fleeing famine, war, and oppression in earlier generations—most of whom never survived the journey.

So I find myself asking: Is comfort quietly eroding our resilience?

Have we buffered ourselves so thoroughly from consequences that we no longer know how to be strong?

Or are we, despite all this, still better off than those who came before us?

Discomfort is a necessary part of being alive. If we are always trying to avoid it, our minds will find it anyway. The answer isn’t in eliminating discomfort. The answer is in choosing hard things—and knowing we can return to the gifts of modern comfort when we truly need rest.

We have indoor plumbing. We have electricity. We have heat and air conditioning. We have safety that previous generations could not imagine. Those comforts are blessings, but they should be a place we recover, not a place we hide from life.

For some people, choosing discomfort might mean training for a marathon. For others, it might mean climbing a mountain or learning a new skill that feels intimidating.

For me, it’s trying to farm in Central Texas. It’s raising four children. It’s working to build a life and livelihood in a way that sometimes feels impossible.

And maybe that’s the balance we’re looking for—not a return to constant danger, but a return to meaningful effort. Not rejecting comfort, but refusing to let comfort define us.