An experienced hostage negotiator has told a committee of MPs “state-level hostage situations” such as the case of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe often revolve around the importance of the Foreign Office recognising they are dealing with a “playground bully.”

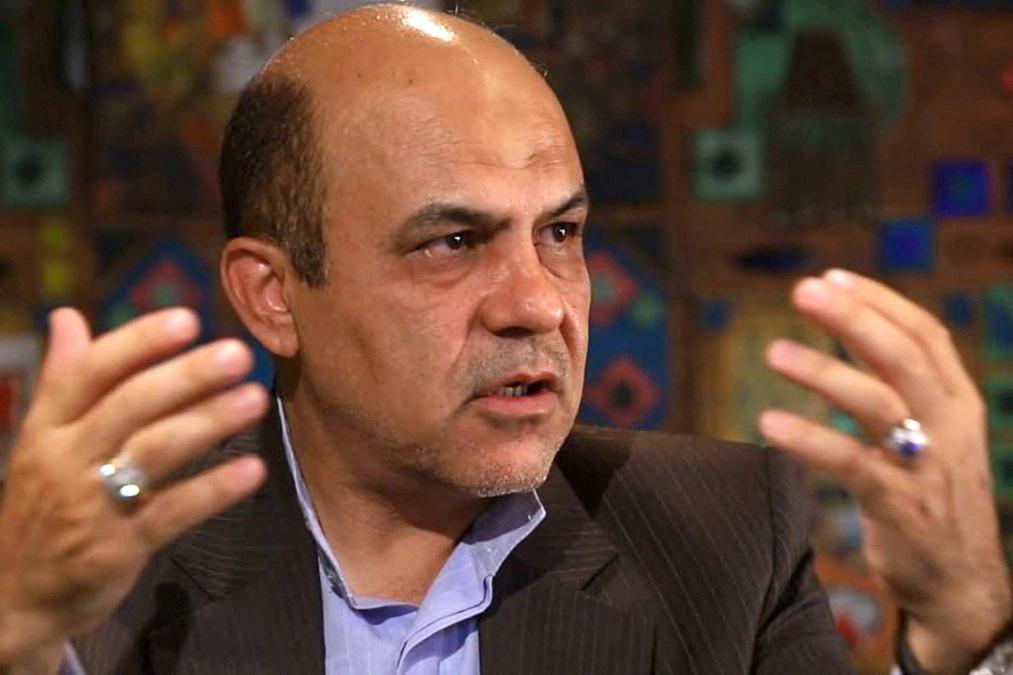

Last month Iran executed Alireza Akbari, a former deputy defence minister in Iran who was also a British national, despite an appeal by Foreign Secretary James Cleverly. Akbari was convicted of spying for MI6, an allegation which he and his family had insisted was false.