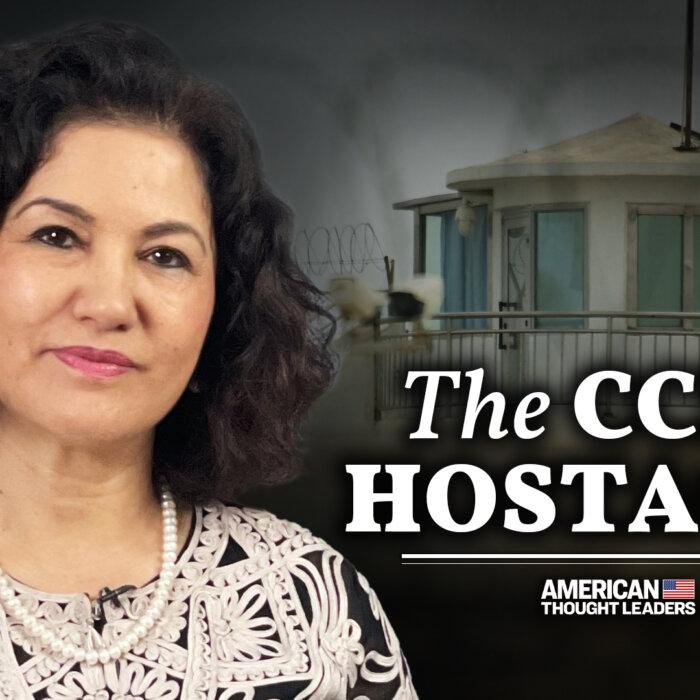

A well-known Uyghur scholar who disappeared from China’s Xinjiang region nearly six years ago has been sentenced to life imprisonment for endangering state security, a U.S.-based rights group said on Sept. 21.

Rahile Dawut, 57, was convicted of “splittism,” or pursuing factional interests in opposition to the ruling party, in December 2018, a year after her disappearance in December 2017. She filed an appeal, but it was denied, the San Francisco-based Dui Hua Foundation said in a statement.

Trials related to charges of splittism are often held in secret, the organization stated.

“The defendant’s lawyer is thought to have attended professor Rahile Dawut’s trials, but it is not known if members of her family were allowed to attend.

“Although there has been speculation that Professor Rahile Dawut was given a long sentence, this is believed to be the first time that a reliable source in the Chinese government has confirmed the sentence of life imprisonment,” it added.

The rights group said that Ms. Dawut’s sentence comes with “the supplemental sentence of deprivation of political rights for life.”

John Kamm, executive director of the Dui Hua Foundation, has called for her immediate release and safe return to her family.

“The sentencing of Professor Rahile Dawut to life in prison is a cruel tragedy, a great loss for the Uyghur people, and for all who treasure academic freedom,” he said.

Ms. Dawut was a professor at the Xinjiang University College of Humanities. She specializes in Uyghur folklore and traditions and has also received awards and grants from China’s Ministry of Culture.

Before her disappearance, Ms. Dawut told a relative that she planned to travel from Urumqi to Beijing. Her family and friends have been unable to contact her since, according to the Scholars At Risk Network.

Chinese authorities haven’t disclosed any information about her whereabouts, health condition, or access to legal counsel or the nature of the charges against her. Her family believed Ms. Dawut was being held at “reeducation camps” in Xinjiang.

“I worry about my mother every single day. The thought of my innocent mother having to spend her life in prison brings unbearable pain,” Ms. Dawut’s daughter, Akeda Pulati, was quoted as saying by Dui Hua.

“China, show your mercy and release my innocent mother.”

Ms. Dawut has written many articles and books, and she also served as a visiting scholar at the University of Pennsylvania, Washington University, Indiana University, and Cambridge University.

‘Serious Human Rights Violations’

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region is in the northwest of China and is supposed to operate as an autonomous region. It’s home to 25 million people of a variety of ethnicities.The Chinese Communist Party, which rules China as one-party state, arbitrarily detains citizens of the Xinjiang province in reeducation and forced labor facilities, under the guise of “anti-terror” or “anti-extremism” law enforcement. Reports of these abuses surfaced in 2016.

“Some of the reeducation camps have closed down, but the prison camps are expanding,” she said, referencing a report in which China said it was building more camps with more permanency.