Locked inside the crowded Chinese prison, blind lawyer Chen Guancheng hid his most treasured possession from the guards—inside a single serve milk box.

A pocket-size shortwave radio.

For three years, Mr. Chen looked forward to the hours after curfew. With a blanket wrapped over his head and the radio’s metal antenna parallel to his body, he lay still as the vibrating device under his ear brought to life a world outside the prison’s walls. Petitioners, protesters, human rights abuses, a grassroots movement to cut ties with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—in that tiny murmuring voice, he saw them all. He was free.

Radio powerhouses—BBC, Deutsche Welle, Voice of America—have either cut back on their China service or moved programs online. Meanwhile, the “Great Firewall,” the regime’s censorship apparatus aimed at isolating China digitally, seems only to grow taller by the day.

Bucking the trend is a largely volunteer-run radio network called Sound of Hope, whose 10 p.m. and midnight segments kept Mr. Chen informed about current affairs in China during his years in prison.

The company now boasts one of the largest shortwave broadcasting networks around China, with about 120 stations beaming signals to China 24/7.

Allen Zeng, Sound of Hope’s co-founder and CEO, sees shortwave as the answer to the regime’s information blackout.

With shortwave radio, though, “they have nowhere to turn it off,” Mr. Zeng said.

A Voice to Trust

An unlikely journey began in 2004 for Mr. Zeng, then a Silicon Valley engineer.Inside China, a massive nationwide campaign had been underway, targeting virtually one in 13 Chinese who live by truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance, the three tenets of the faith group Falun Gong.

“We had to do something about it. We needed to stop the killing,” he said.

The first thing that came to mind was the shortwave radio that had been a household item in China since the Cold War era, one that in 1989, Mr. Zeng and other college students had turned to for information when authorities rolled their tanks over democracy-loving demonstrators in Tiananmen Square.

“Because nothing else could be trusted,” he said.

With little budget and know-how, the team started small: leasing one hour of airtime from Taiwanese national broadcaster Radio Taiwan International.

It was such a hit in Beijing that shortwave radios were out of stock for months.

The response, and occasional words of encouragement from listeners who managed to bypass China’s internet censorship, kept Mr. Zeng’s team going. Dissidents chipped in and programs diversified. Soon, they were Radio Taiwan International’s biggest contractor.

Gauging the size of the network’s audience is difficult given the opacity of data from China.

But Sound of Hope became so influential that it caught Beijing’s attention. The Chinese regime began to pressure the radio network’s Taiwanese partner.

‘Walking in the Dark’

Giving up wasn’t in Mr. Zeng’s vocabulary.As the partnership with Taiwan unraveled, the engineers raced to develop their own solutions. They drew inspiration from fishing vessels’ radio waves to build their own transmitter.

The result was a mini-tower based in Taiwan with upward-facing antennas that spread out like wings. They nicknamed it “Seagull.”

The team set its sights low. The first “seagull” had a power level of 100 watts—a thousandth of the smallest radio service they had leased from the Taiwanese broadcaster.

“It was the only thing we could afford,” Mr. Zeng said.

“Seagull” No. 1 was short-lived, and so were many of its successors whose signals the Chinese authorities quickly jammed. But to the team, it was a major discovery: At 100 watts, they still had a chance to be heard.

They kept producing and tweaking their equipment with each new creation.

“It was just like walking in the dark—we didn’t know whether there would be an end to this tunnel,” Mr. Zeng said.

Finally, on the 16th try, they saw a breakthrough. The signal broke through and held steady.

Mr. Zeng figured that they had, for the moment, consumed all the jamming power from China.

Expansion

Technical challenges aside, getting the stations to work was no easy feat.The wilderness, their best location for an uninterrupted signal, is also a haven for creepy crawlers, from scorpions to snakes. Hsieh Shih-mu, a volunteer, stepped on a snake once and sighted many more while building some of the earliest “seagulls” in Taiwan’s southern tip. Often, after wobbling back home on a motorcycle on the pitch-black mountain road, he was covered in mosquito bites.

Narrow and muddy, the path became doubly treacherous after rain. One time, another volunteer nearly fell off the hill—and would have, if not for the roadside tree branches that caught his motorcycle. They had to call a tow truck to haul the man back up.

Mixing concrete, welding metals, and erecting shafts, they put it all together from scratch. If one step went wrong, their lives were on the line.

Even after a radio tower was up and running, parts aged and failed. Beijing’s interference, wildlife, harsh weather, anything could get in the way. Someone had to monitor the signal constantly, ready to mitigate any hiccup.

“We didn’t know how much impact we were having, but we heard that this was something workable, so we just got on with it,” Mr. Hsieh told The Epoch Times. “And we kept at it.”

His spot, perched atop a mountain one strait away from the mainland, covered southern China’s Pearl River Delta, a key Chinese manufacturing and economic hub.

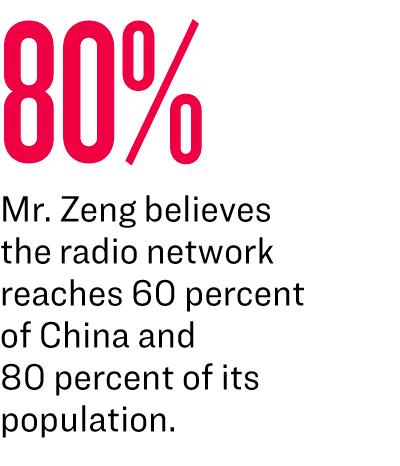

Today, by a “modest estimate,” Mr. Zeng believes the entire radio network reaches 60 percent of China and 80 percent of its population, including the heavily surveilled Tibet and Xinjiang.

Blows

Unable to block Sound of Hope’s airwaves in the sky, the CCP moved to target the network’s infrastructure on the ground.After tracking signals to find the locations of the “seagulls,” regime operatives pressured the host countries to wipe the radio network off the map.

One target was the Sound of Hope “seagull” in northern Thailand. In August 2018, the station was raided by police, who dismantled the equipment and took everything from the station—even electric fans, according to Taiwanese businessman Chiang Yun-hsin, who oversaw operations there.

“It was just mind-blowing,” he told The Epoch Times.

Mr. Chiang was arrested that November and driven overnight to a Bangkok police station.

Upon his arrest, Mr. Chiang learned from one of the police officers that Chinese police had located their office through satellite images. Chinese police were so intent on action that they flew to Bangkok to demand that their Thai counterparts take down the network. The prosecutor later told his attorney that the Chinese Embassy was adamant that he be sent to prison.

“They wanted to make an example of me,” Mr. Chiang said.

Mr. Chiang, who practices Falun Gong, said the Chinese authorities had strained to cast a negative impression of him by maligning his faith among their Thai counterparts. When Mr. Chiang was meditating on the first morning of his detention, a Thai officer was struck by his peaceful demeanor and wondered aloud why he was described as a dangerous man.

Eventually driven out of Thailand with a 10-year ban, Mr. Chiang returned to Taiwan with no regrets—he was doing the right thing, he said.

From across the strait, Mr. Chiang had read about the grueling torture that killed many participants in Chinese prisons and met several who had to forsake their homeland for survival.

The Precious Radio

Mr. Chen, a self-taught lawyer who advocated for the poor in China, got his first shortwave radio in the 1990s. Until 2012, when he fled to the American Embassy and won his bid for freedom in the United States, he never failed to have one around him for as long as he was able.During the intermittent home confinement and jail stints for his human rights advocacy, the device was his eyes and ears, allowing him to stay plugged in to the world.

When authorities threw him into prison for speaking out against the regime’s forced abortion policy, he smuggled in a radio, and with the milk box scheme, tricked omnipresent cameras, watchful inmates, and wardens who rummaged through their items every two weeks.

Even with smartphones and computers as ubiquitous as they are today, this time-tested technology is still relevant, especially in rural China, said Mr. Chen. Its low price tag remains hard to beat, as is its capacity to inform, independent of internet availability.

“It’s one-way communication, but it’s still critical,” he told The Epoch Times. “Even if you get locked up, at least your thoughts won’t become out of step with this society.”

Mr. Chen described Sound of Hope as “more grounded” for its detailed reporting on China’s social affairs.

“Someone has to keep an eye on the suffering in that part of the world and put it under the international limelight,” he said. “There should be more resources dedicated in this area.”

As many others retreat, Sound of Hope promises to do just that.

“This is what the Chinese government is afraid of most,” Mr. Zeng said. If it isn’t, “why do they take so much effort to jam it, even up to today?”