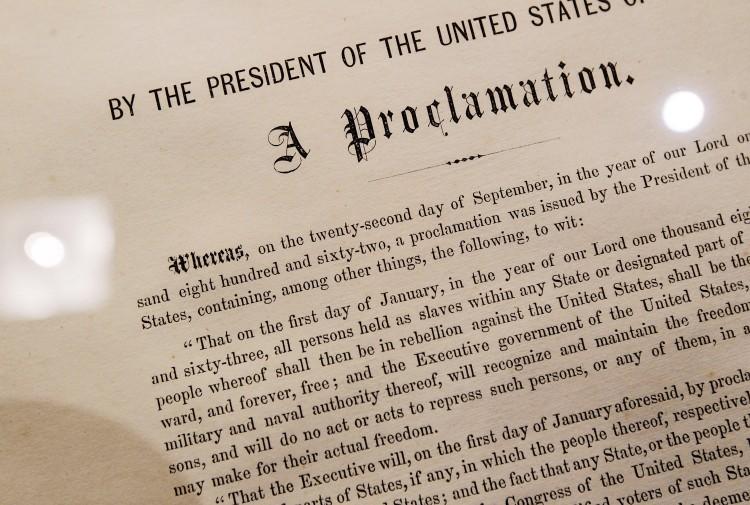

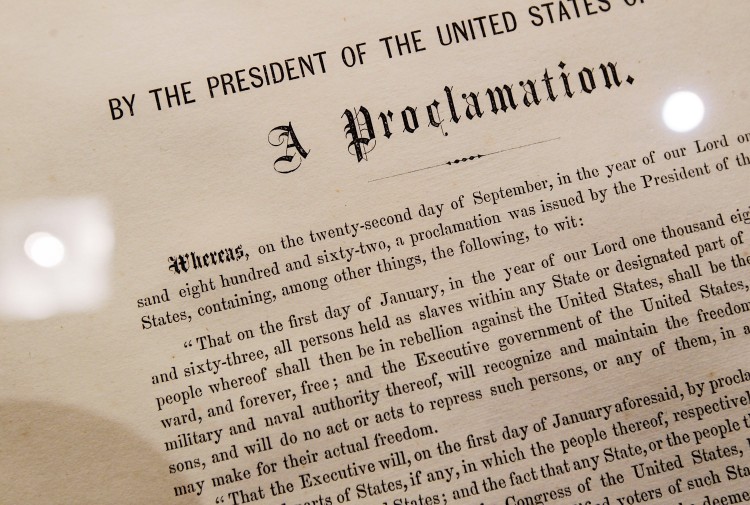

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation Turns 150

The Emancipation Proclamation marked the end of American slavery, but the document was actually a military measure.

One of only 25 copies of the Emancipation Proclamation: Abraham Lincoln's historic edict that led to outlawing slavery in America. The document, originally a military measure, is now 150 years old. Chris Hondros/Getty Images

|Updated: