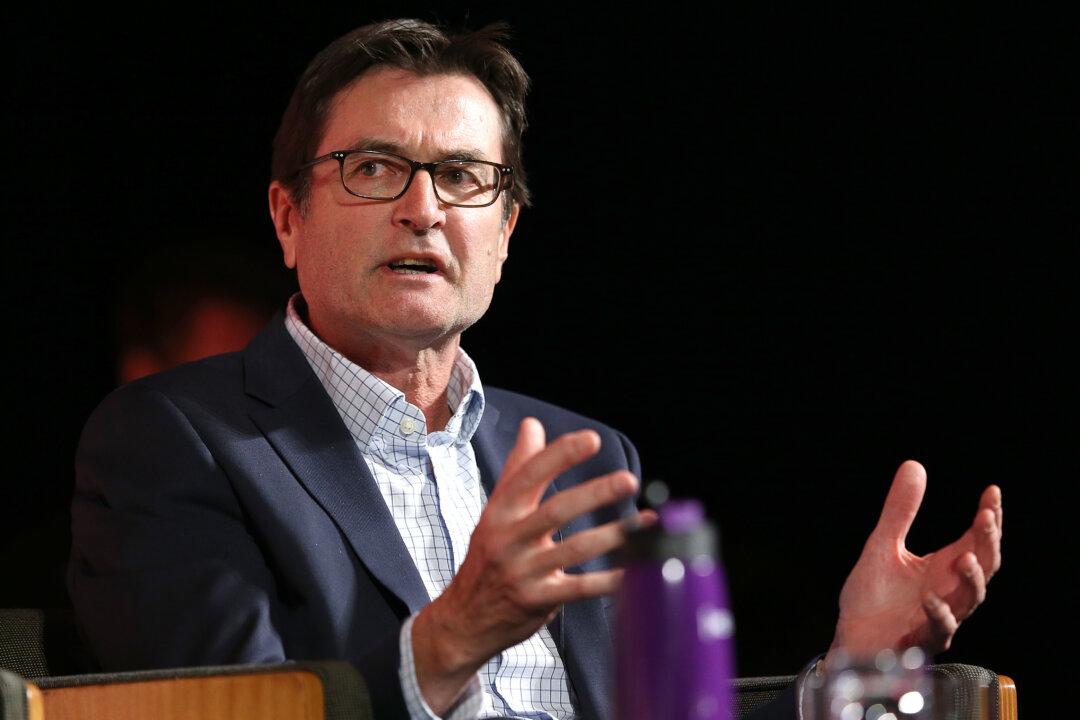

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has recently acknowledged the economic risks that many purport climate change poses to Australia but is confident the nation is more than capable of weathering the storm.

“We have an optimistic view about the future, and one of the reasons we are optimistic about the future is if we get the policy settings right in this defining decade, then we can be major beneficiaries and not victims of the shifts underway,” Mr. Chalmers said at a press conference in Canberra today.