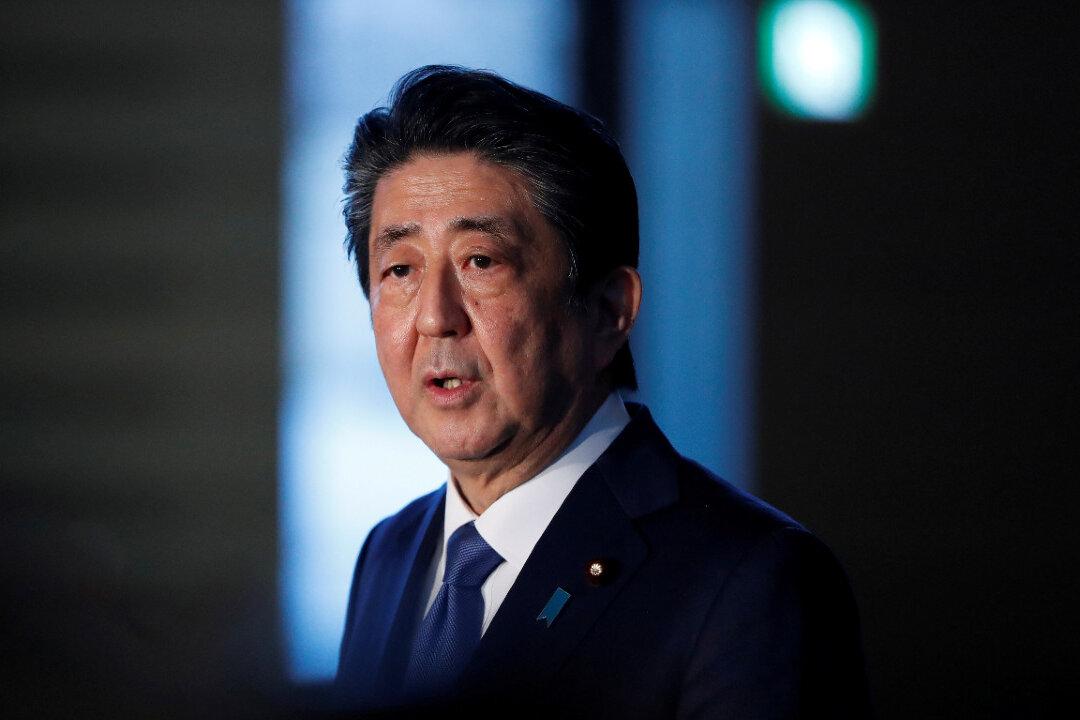

TOKYO—Japan is to impose a state of emergency in Tokyo and six other prefectures as early as Tuesday to contain the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) virus, commonly known as novel coronavirus, while the government prepares a $990 billion (108 trillion yen) stimulus package to soften the economic blow.

Domestic infections topped 4,000, Jiji news reported, and 93 have died—not a huge outbreak compared with some global hot spots. But the numbers keep rising, with particular alarm over the spread in Tokyo, which has more than 1,000 cases including 83 new ones on Monday.