Economic decoupling from China gathered steam during the pandemic when the vulnerability of supply chains came to the fore. But Canada’s economic linkages with China haven’t diminished, despite its closest ally the United States actively doing so.

Whether it’s called decoupling or friendshoring or nearshoring, international trade expert Eric Miller says it’s primarily about reducing risk—de-risking—in trade with China and then adjusting to the impacts.

“The bottom line is there is a process of slow decoupling that’s not being driven by governments. But government policy has tended to be heavy on the rhetoric and light on the implementation,” Mr. Miller, president of Rideau Potomac Strategy Group, said in an Aug. 1 interview.

Some policy-makers and analysts are strong advocates for reducing or cutting ties with China, while others say it’s basically impossible and would be too harmful economically. In an era of elevated inflation, governments recognize that reconfiguring supply chains would further exacerbate cost pressures.

But evidence suggests that decoupling of China from the West is quickening, wrote Adam Slater, lead economist at Oxford Economics (OE), in a July 24 analysis.

“Foreign direct investment (FDI) trends and surveys of China-based Western firms suggest decoupling is likely to be increasingly visible over the coming years,” Mr. Slater said.

“Besides the U.S., evidence of trade decoupling is harder to find.”

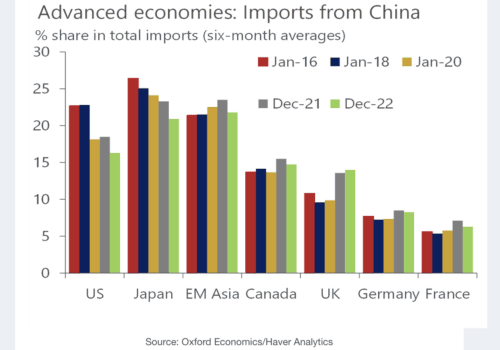

An OE chart of imports from China by advanced economies shows a notable drop from 2016 to 2022 by the United States and Japan, while Canada, among others, has either stayed level or gone up.

Canada Structurally Different From United States

The justifications for decoupling from China are compelling, especially for Canada given allegations of foreign interference such as in elections along with irritations like Beijing’s three-year trade ban on Canadian canola.

Canada has severed ties with the Beijing-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and has ordered China to divest from certain critical mineral investments. But in some respects, Canadian economic ties with China are stronger than many other Western democracies.

“Canada could do more if it wanted to. For example, it could look at how it can get more consumer goods from, say, Southeast Asia with Vietnam, where it has a free-trade agreement,” Mr. Miller said.

He added that Canada’s view on decoupling has been to work with allies on select initiatives rather than deal with the bulk of trade.

“Canada, as a country that relies much more on global supply chains to be traded as a share of GDP [gross domestic product], is much larger than the U.S. And so you have a situation where Canada hasn’t developed a strategy to really make more at home,” Mr. Miller said.

He gave the example that Canada has not seen an appreciable decline in imports of consumer goods from China, due to lack of an alternate source, and that the United States doesn’t really have this problem.