Former Australian Treasurer Peter Costello has warned that the current national migrant intake must be managed carefully to find an equilibrium in which a struggling economy is supported without placing upward pressure on inflation.

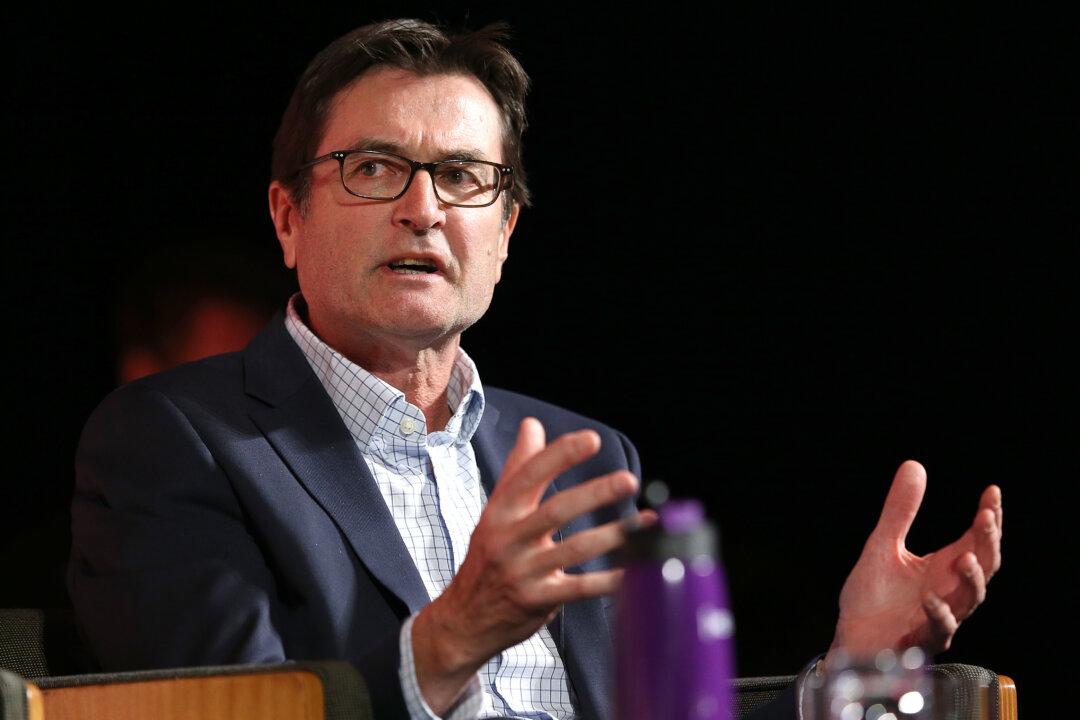

Speaking at the UBS Australasia Conference on Monday, Mr. Costello drew comparisons between Australia’s current and past immigration levels.