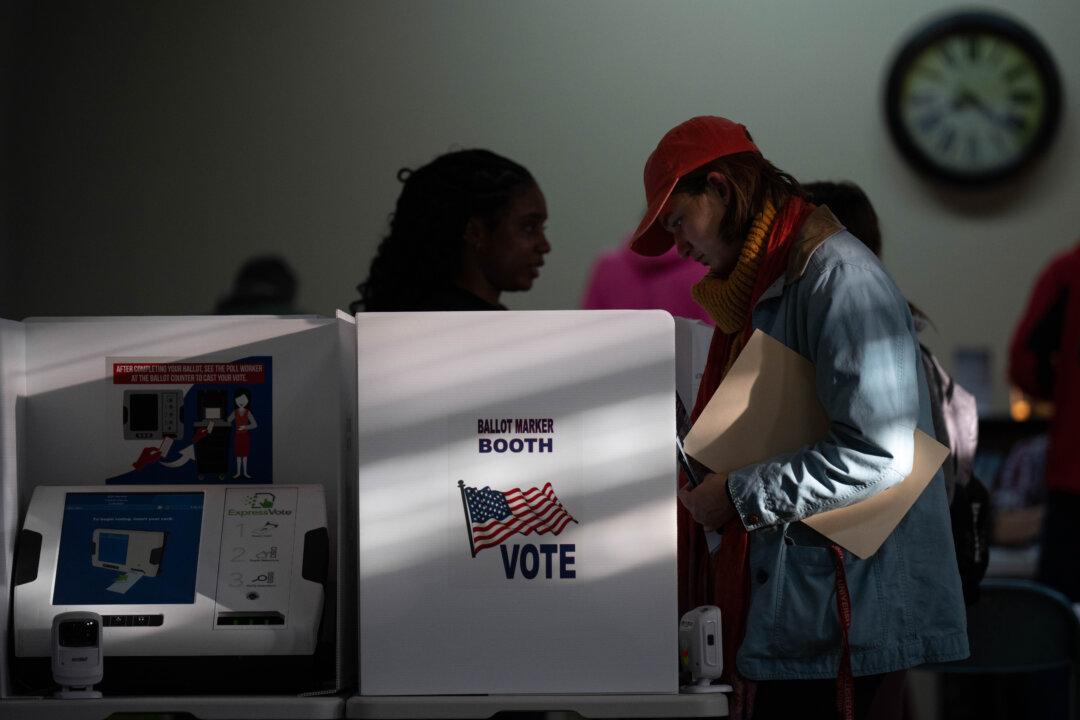

Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose says many municipal and county elections are decided by one vote, so it’s vital that citizens cast their votes with confidence.

“If an election can come down to a single vote, then a single fraudulent vote is too many,” LaRose told The Epoch Times.