Mount Kasotachi, a little volcanic island that makes up part of Alaska’s Aleutian chain, sent an ash plume 45,000 feet up into the atmosphere in August of 2008.

Being very remote and uninhabited, except for researchers stationed there, this explosive event received little attention from the general public.

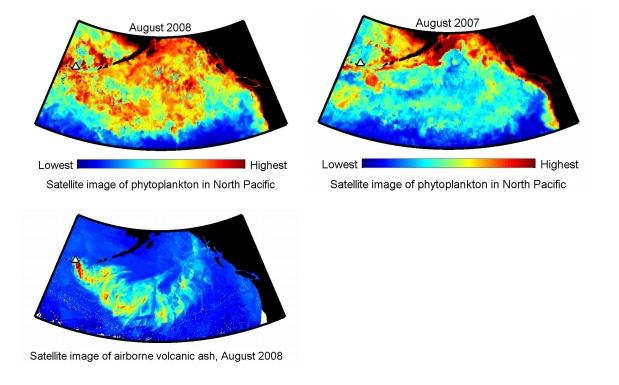

But fortunately researchers in North America noticed the effect via satellite.

Led by oceanographer Roberta Hamme at the University of Victoria, a joint U.S.-Canadian team observed that areas of the North Pacific affected by the iron-laden ash cloud underwent an “ocean productivity event of unprecedented magnitude,” Hamme said in a press release.

The bloom was the largest in the area at least since satellites began measuring ocean chlorophyll levels in 1997.

Phytoplankton are a variety of microscopic organisms that live near the surface of most sea- and freshwater, where plenty of sunlight is available for photosynthesis. They form the bottom of the marine food chain, and are thought to account for half of all the photosynthetic activity that takes place on Earth.

During their growth, phytoplankton absorb carbon dioxide. When they die, this carbon is carried deep into the ocean, away from the atmosphere where it could have contributed to the greenhouse effect.

The researchers believe the massive bloom was due to the ash cloud acting as a fertilizer. Oceans are generally low in iron, which may be a limiting factor in phytoplankton growth.

In the quest to offset carbon dioxide generated by fossil fuels, the idea of fertilizing the world’s oceans to encourage more photosynthesis to take place has been hotly debated.

However, the researchers estimate that only 0.01 petagrams of carbon dioxide was sequestered during this event. (A petagram is 1015 grams or a billion metric tonnes).

This is a modest increase when compared with the annual uptake by the world’s oceans of 2 petagrams of carbon dioxide and 6.5 petagrams released by burning fossil fuels each year.

“The event acts as an example of the necessary scale that purposeful iron fertilizations would need to be to have an impact on global atmospheric carbon dioxide levels,” Hamme concluded.