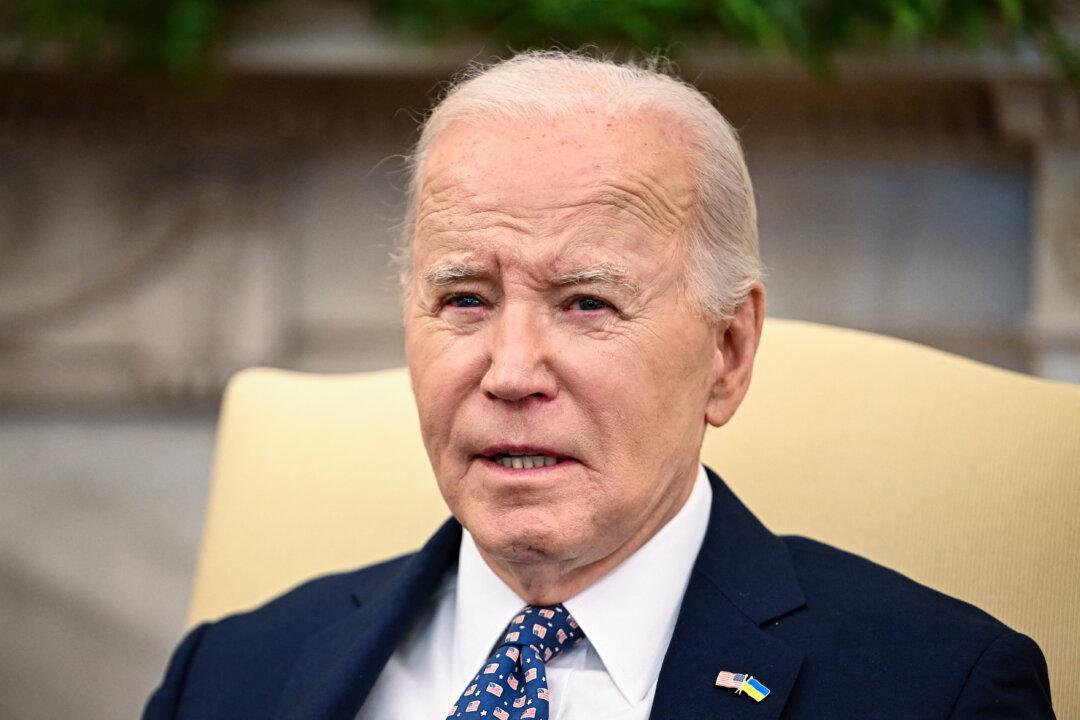

As part of efforts to clamp down on what the current administration calls greed-flation, President Joe Biden will launch a new joint “strike force” to fight “unfair and illegal” corporate pricing, the White House announced.

The latest task force creation will be led by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice.