Less than three years after the Treaty of Paris ended America’s War for Independence in 1783, the infant nation still struggled to find its footing. Great Britain’s overreach of power—its writs of assistance, quartering of troops, and lack of jury trials—was still fresh in Americans’ memories, making many wary of concentrating too much authority in a centralized government. Yet it had become clear that the new nation’s Articles of Confederation were too weak to command order among the 13 states. Something had to be done.

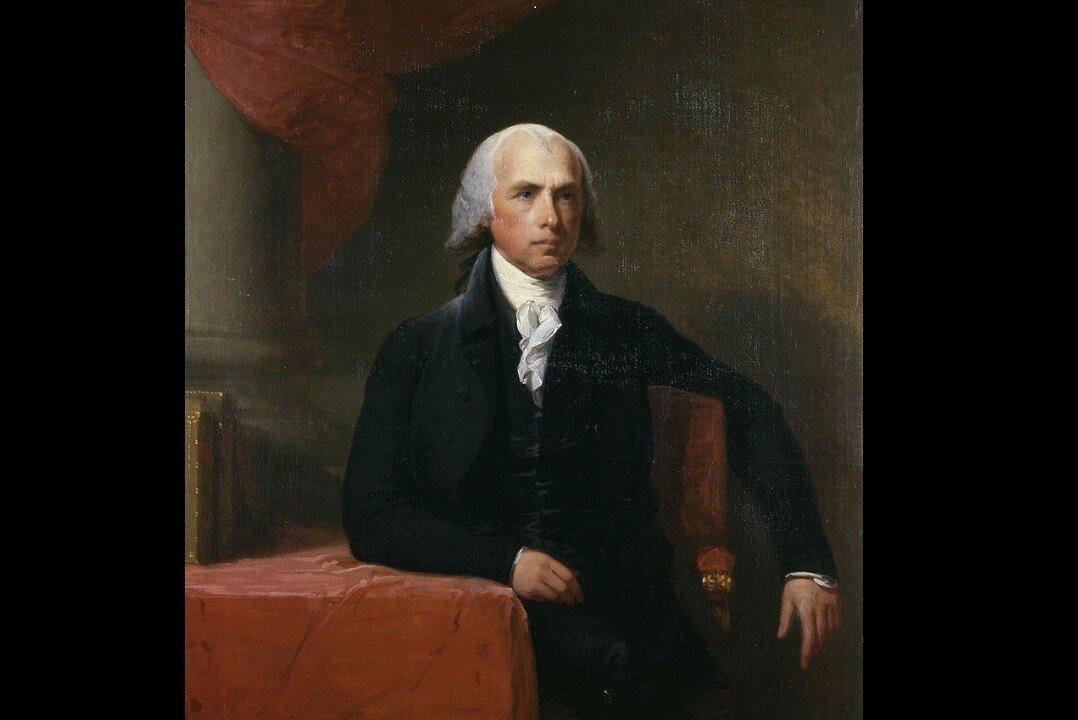

In May 1787, delegates convened in Philadelphia to discuss a solution. For the next four grueling months, they debated, dissembled, and ultimately discarded the Articles of Confederation, drafting in its place the framework for the United States Constitution. Many issues were on the table—most heatedly, federal and executive power, representation in Congress, and commerce across state borders. Of the 55 delegates in attendance, only 39 signed the final document.