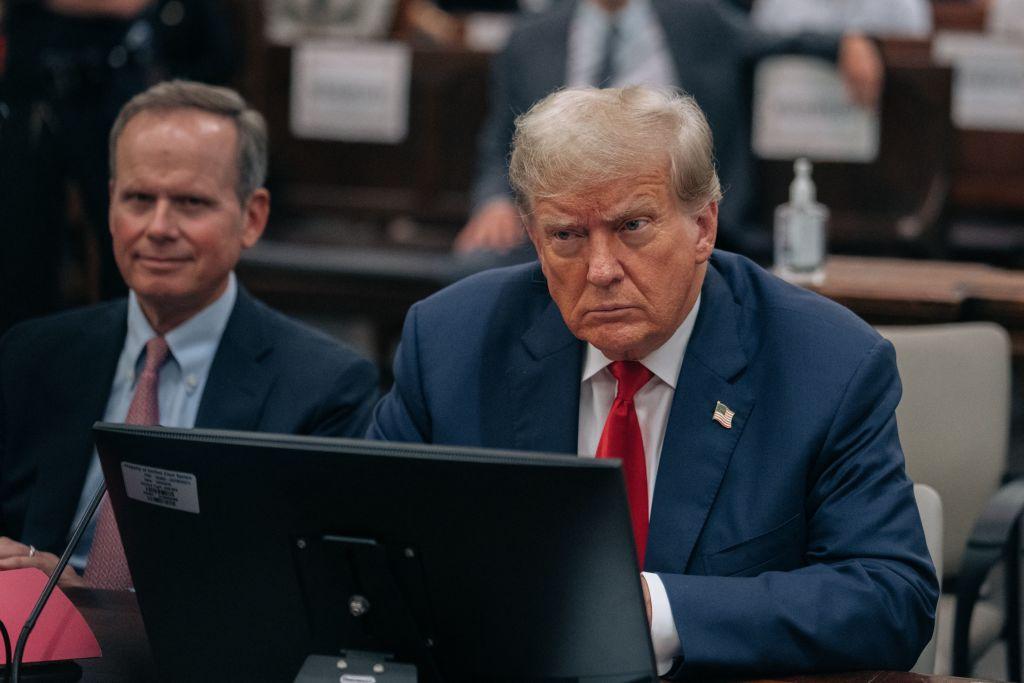

Special counsel Jack Smith’s office filed two motions on Tuesday, in which it pressed for the defense’s legal strategy, and asked the court to potentially hide juror identities from former President Donald Trump in the federal criminal case against him in Washington alleging he illegally interfered with the 2020 elections. The filings note that the defense has opposed both motions.

The prosecutors argue that President Trump has talked publicly about using an advice-of-counsel defense, which would allow him to say that he was acting on the legal advice of attorneys when he challenged the 2020 election results. If the former president uses such a defense, however, “he waives attorney-client privilege for all communications concerning that defense,” the filing reads.