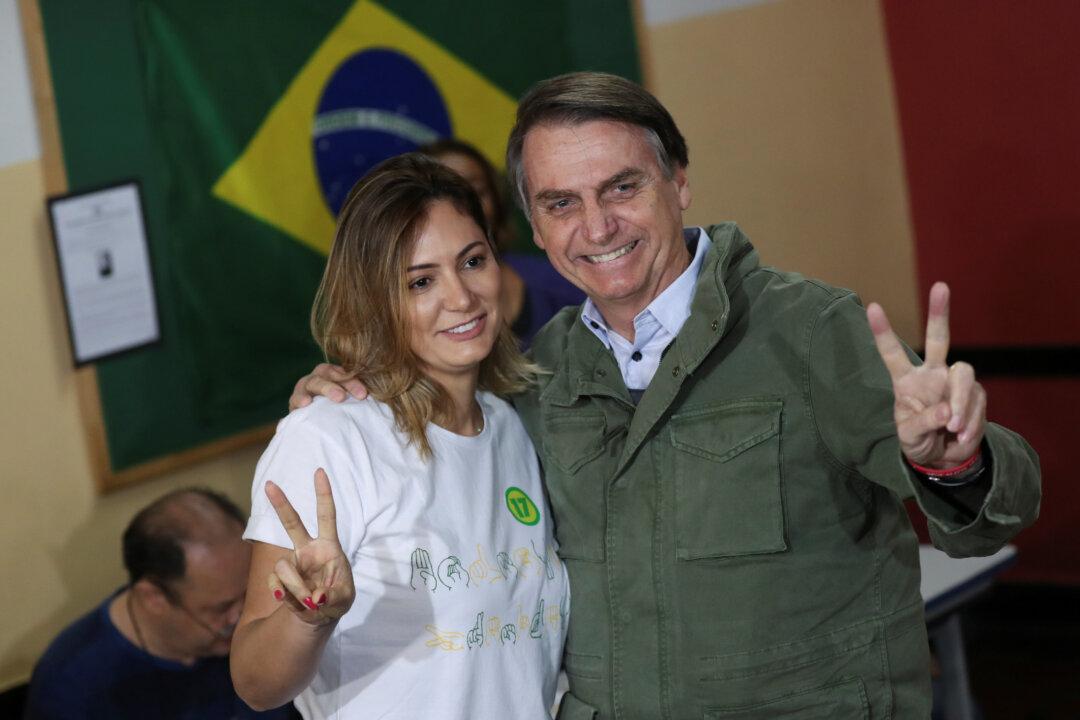

In 2009, China surpassed the United States as Brazil’s leading trade partner, but that is likely to reverse with Jair Bolsonaro in power. Brazil’s president-elect, a retired army captain and conservative lawmaker who was elected with 55 percent of the vote, has vowed to end the open-arms approach to Beijing.

Evidently on edge, the Chinese foreign minister on Oct. 29 sent carefully worded congratulations: “China develops relations with other countries in light of the one-China principle. We would like to work with Brazil to update the comprehensive strategic partnership on the basis of mutual respect for each other’s core interests.”