Commentary

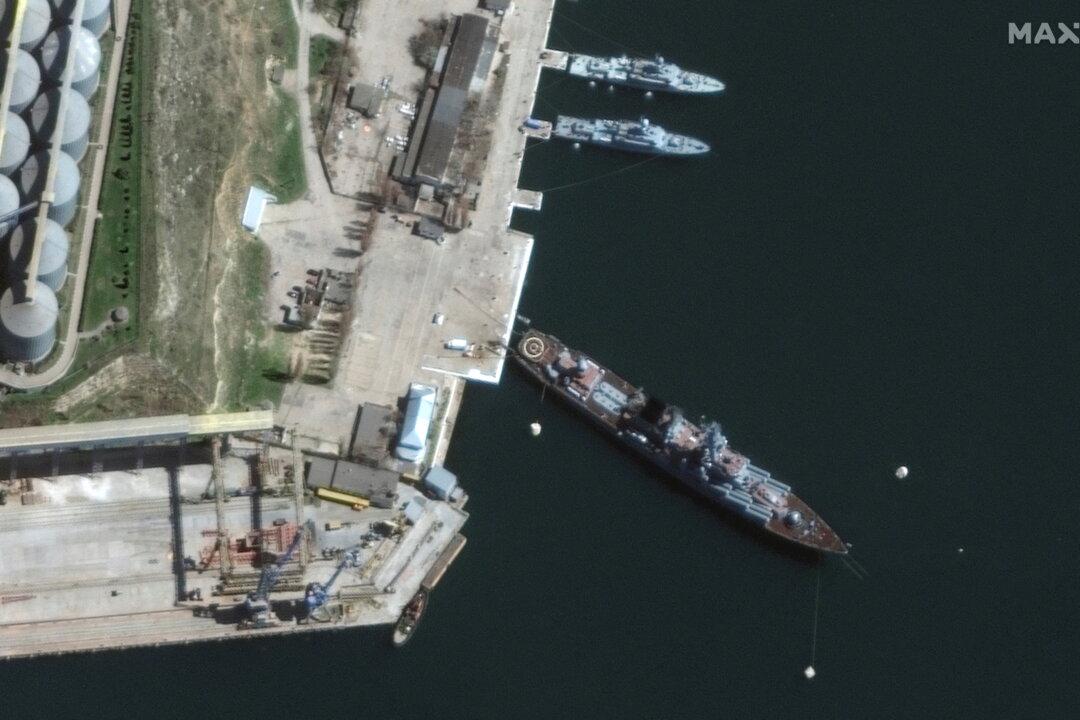

The unanticipated sinking of the Moskva, the flagship of the Russian navy’s Black Sea fleet, on April 14 garnered worldwide attention. It led to intense speculation about how it will impact Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine.

The unanticipated sinking of the Moskva, the flagship of the Russian navy’s Black Sea fleet, on April 14 garnered worldwide attention. It led to intense speculation about how it will impact Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine.