Until 1969, biologists thought mushrooms and other fungi were plants. They’re actually more closely related to animals, but with enough differences that they inhabit their own distinct classification.

This and more recent findings about these mysterious organisms illustrate how much we have yet to learn about the complexities of the natural world. New research reveals mushrooms can even help plants communicate, share nutrients, and defend themselves against disease and pests.

There’s far more to mushrooms than the stems and caps that poke above ground. Most of the organism is a mass of thin underground threads called mycelia. These filaments form networks that help plants, including trees, connect to each other, through structures called mycorrhizae.

Scientists believe about 90 percent of land-based plants are involved in this mutually beneficial relationship with fungi. Plants deliver food to the mushroom, created by photosynthesis, and the filaments, in turn, assist the plants to absorb water and minerals and to produce chemicals that help them resist disease and other threats. And, of course, a myriad of other life forms benefit from the healthy plants.

The structure and function of the mycelial networks and their ability to facilitate communication between physically separated plants led mycologist Paul Stamets to call them “Earth’s natural Internet.” He’s also noted their similarity to brain cell networks. According to a Discover article, “Brains and mycelia grow new connections, or prune existing ones, in response to environmental stimuli. Both use an array of chemical messengers to transmit signals throughout a cellular web.”

Research by Suzanne Simard at the University of British Columbia found that Douglas fir and paper birch trees transfer carbon back and forth through the mycelia, and other research shows they can also transfer nitrogen and phosphorus. Simard believes older, larger trees help younger trees through this process. She found that the smaller trees’ survival often depends on large “mother trees” and that cutting down these tree elders leaves seedlings and smaller trees more vulnerable.

Researchers in China found trees attacked by harmful fungi are able to warn other trees through the mycelia networks, and University of Aberdeen biologists found they can also warn other plants of aphid attacks.

It all adds to our growing understanding of how interconnected everything on our planet is, and how our actions—such as cutting down large “mother” trees—can have unintended negative consequences that cascade through ecosystems.

Scientists are also finding that fungi can be useful to humans beyond providing food and helping us make cheese, bread, beer, and wine. Stamets believes mushrooms can be employed to clean up oil spills, defend against weaponized smallpox, break down toxic chemicals like PCBs, and decontaminate areas exposed to radiation.

He credits his interest in fungi to another fascinating aspect of many mushrooms around the world: their hallucinogenic properties. During college, Stamets spent a lot of time in the Ohio woods, where he first tried psilocybin mushrooms. They had a profound effect on him, and after his first experience, his persistent stutter went away. He later quit a logging job, because the work was destroying mushroom habitat, and began studying fungi at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington.

Since then, his research has led to fascinating discoveries of multiple possible purposes for fungi, including nuclear decontamination, water filtration, biofuels, increasing agricultural yields, pest control, and medicines.

Research is also shedding light on potential benefits of the psychotropic properties of mushrooms, such as the 144 species that contain psilocybin. Indigenous people have long used hallucinogenic mushrooms for ceremonial, spiritual, and psychological purposes—and with good reason, it turns out. Psilocybin has been shown to improve the brain’s connectivity. Researchers are finding the chemical can help combat depression, anxiety, fear, and other disorders, and increase creativity and openness to new experience. This makes them potentially beneficial for post-traumatic stress, addiction, and palliative care treatments.

We humans have made a lot of technological and scientific advances, and this sometimes gives us the sense that we’re above or outside of nature, that we can do things better. Sometimes it takes a fascinating lifeform like a mushroom to shake us from our hubris and show us how much we have yet to learn about the world and our place in it.

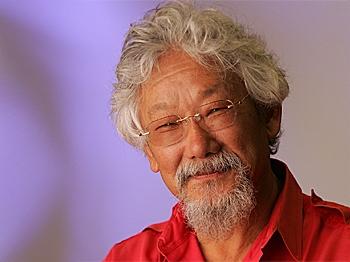

Written with contributions from Ian Hanington, senior editor with the David Suzuki Foundation.

Opinion

The Many Marvels of the Mysterious Mushroom

Until 1969, biologists thought mushrooms and other fungi were plants. They’re actually more closely related to animals, but with enough differences that they inhabit their own distinct classification.

David Suzuki

|Updated: