June 4 marks two 32nd anniversaries: the first one commemorates the defeat of the ruling Polish communist party in the partly-free election, the second one commemorates the bloody crackdown by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on a peaceful student protest at Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

On June 4, 1989, the ruling Polish communist party, called The Polish United Workers’ Party (PUWP) was defeated in the hybrid election in communist Poland.

The election format was agreed upon during the negotiations held earlier in 1989 between the Polish communist government camp and so-called “Solidarity” camp, said Prof. Jacek Reginia-Zacharski, Ph.D., political scientist and historian at the University of Lodz in Poland.

The Polish “Solidarity” movement emerged in 1980 out of Polish workers protesting against deteriorating living conditions in communist Poland. Solidarity became the first free trade union in the Eastern (communist) Bloc that was independent of the regime and quickly grew as an anti-communist opposition group demanding economic and political reforms in the country.

By early 1981 Solidarity’s membership reached 10 million and included 80 percent of the Polish workforce. In response, the communist government declared martial law to crack down on the movement.

After martial law was lifted in 1983, the Solidarity movement started emerging again even though the regime’s repression against its members continued. In 1988, when a big wave of strikes spread throughout the country, the Polish communist government expressed its willingness to negotiate with Solidarity.

About 6 months later, the round table talks started between the Solidarity-led opposition and the coalition led by the ruling communist party, officially called PUWP.

“The communists did not want to relinquish power unconditionally,” Reginia-Zacharski said. The negotiating parties agreed to create the upper chamber of the parliament–Senate–which had not existed before and to make the election to the Senate free, he explained.

However, the communists wanted to assure that they would hold a majority in the lower chamber of the parliament, which was the main one, and reserved for themselves 65 percent of the seats, the scientist explained, adding that only candidates approved by the coalition could run for these seats.

Therefore the election in 1989 could not be considered partially free, it was rather a hybrid election, Reginia-Zacharski said, adding that it was not considered free by the Council of Europe.

On June 4, 1989, Solidarity candidates won 160 seats out of 161 available to them while the communist candidates won only 5 seats out of 299 reserved for them, with 62 percent voter turnout. In addition, 92 out of 100 Senate seats went to Solidarity and the communists won none.

“It was indeed a shock to the communists. It was a disaster from their point of view,” Reginia-Zacharski said. He believed that the results of the first round of the election were a surprise to all.

A sense of trepidation was felt on both sides of the political fence, Reginia-Zacharski continued, because a considerable number of Solidarity activists and probably a big portion of the Polish society feared that the communists, facing such a disaster, could resort to the use of force as they did in 1981 when they imposed martial law on the country.

The economic situation in Poland at that time was very grim, Reginia-Zacharski said. “The hyperinflation raged, wages in Poland peaked at millions but the purchasing power of the Polish currency dropped to almost nothing.”

In Reginia-Zacharski’s opinion, dramatic and traumatic news about the massacre on Tiananmen Square in Beijing that broke on the election day fueled such fears. “The martial law inflicted very deep trauma on the Polish society,” he added.

The second round of the election was needed to fill out vacant seats, but the electoral law did not allow candidates who had not received the required 50 percent of the votes to run in the second round, Reginia-Zacharski said. Therefore the communist government changed the electoral law to allow candidates who lost the first round to run in the second one, he explained.

As a result of the second round, which took place on June 18, Solidarity won one lower chamber seat allotted to free election candidates but vacant after the first round and gained 7 out 8 remaining seats in the Senate. One remaining Senate seat was filled by an independent candidate. Communists had no representation in the Senate.

Election Aftermath

The impact of the election turned out to be much bigger than it seemed, Reginia-Zacharski said. Despite the fact that Solidarity only had 161 seats out of 460 in the lower chamber, the so-called deconstruction of the communist camp started shortly after the election.

The political arrangement designed during the round table negotiations was supposed to function after the election but it was never realized, Reginia-Zacharski said.

Activists of satellite parties that formed a coalition with the communists were clear that “the communists do not have absolutely any support ... [and] The Polish United Workers’ Party [PUWP] after the June election ceased being a hegemonic political group in Poland,” Reginia-Zacharski said.

The Polish communist party’s membership had shrunk from about 3 million in 1980 to about 1 million in the fall of 1989. In January 1990, the PUWP dissolved itself.

June 4, 1989, at Tiananmen Square

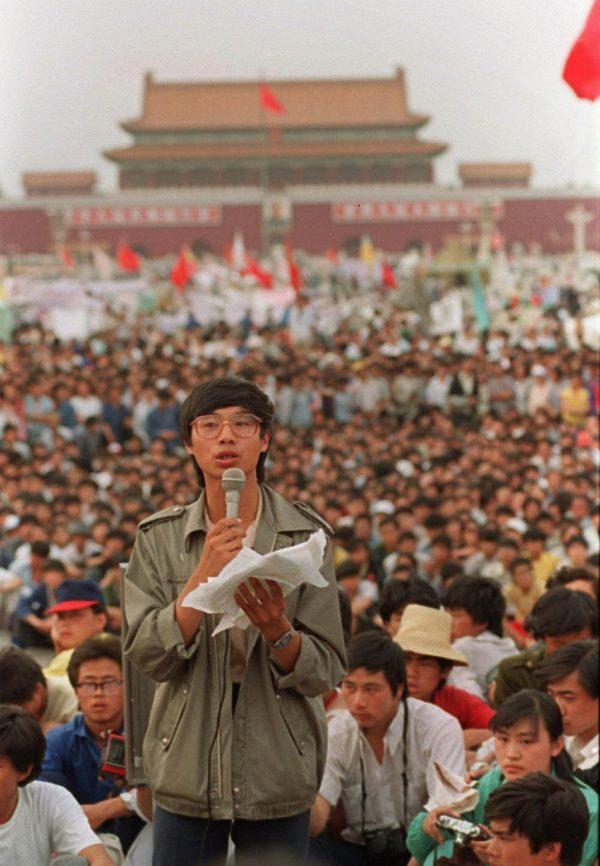

The protesters—college students and university staff from around the country joined by the nationwide demonstrations—called for human rights, an end to corruption, and democratic reform.

It is possible that Chinese communist leaders were watching processes and changes taking place in the Soviet Union and in the Eastern Bloc including Poland, and were clear that “these processes once started had tremendous potential to escalate, [and] it was something that could not be stopped,” Reginia-Zacharski said. It is not known however if these observations influenced their decision to brutally quell the protest, he added.

The New York Times reported in 1989 that Jiang Zemin, who had become the General Secretary of the CCP in the wake of the bloody resolution of events on June 4, corrected an Italian reporter who used the term “Tiananmen tragedy” in his question to Jiang.

According to the New York Times, Jiang said, “I'd like to correct you in your use of the word tragedy. We do not believe that there was any tragedy in Tiananmen Square. What actually happened was a counterrevolutionary rebellion aimed at opposing the leadership of the Communist Party and overthrowing the socialist system.”