Commentary

You’ve Been up for 22 Hours and Haven’t Eaten in 12: ‘Don’t Miss’

A veteran reflects on the stresses of life in the military. The structure of military life helps compensate for lack of sleep and extreme conditions; but without that structure, vets experience the toll that those extreme conditions take.

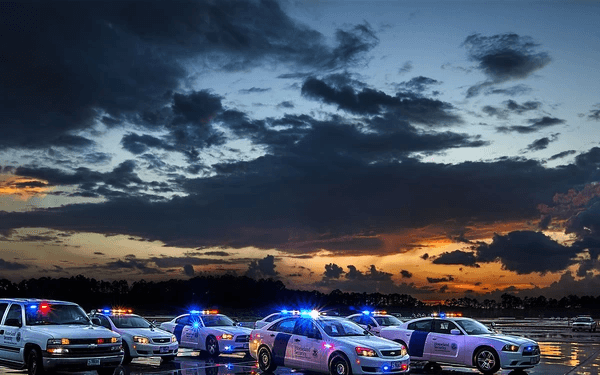

Crew members of the Coast Guard Cutter Glenn Harris pull a person from the water after a 175-foot commercial lift boat capsized 8 miles south of Grand Isle, La., on April 13, 2021. U.S. Coast Guard via AP